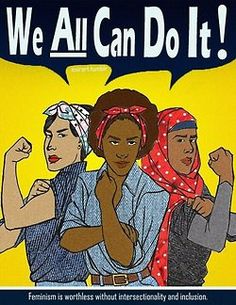

YAE Camp was a partnership between several female-directed nonprofits and collectives. YAE! summer camp for young girls was an immersive experience designed to build confidence and empowerment for female identifying youth inside of typically male dominated artistic spaces. YAE! provides mentorship for female/femme/non-binary youth ages 12 to 17 years old. Participants came from diverse, historically marginalized communities, and under-served low-income homes in Portland are given top priority in the scholarship program. Students came from all different levels of technique and experience in visual art and dance. By the end of YAE!, campers learned the basics of aerosol painting and safety, and will have completed a large-scale permanent mural in SE Portland. Campers also showcased a dance they have helped choreograph and participate in a freestyle/cypher/jam session with local female dance artists.

Midnite Special

Event Review by Loudres Jimenez

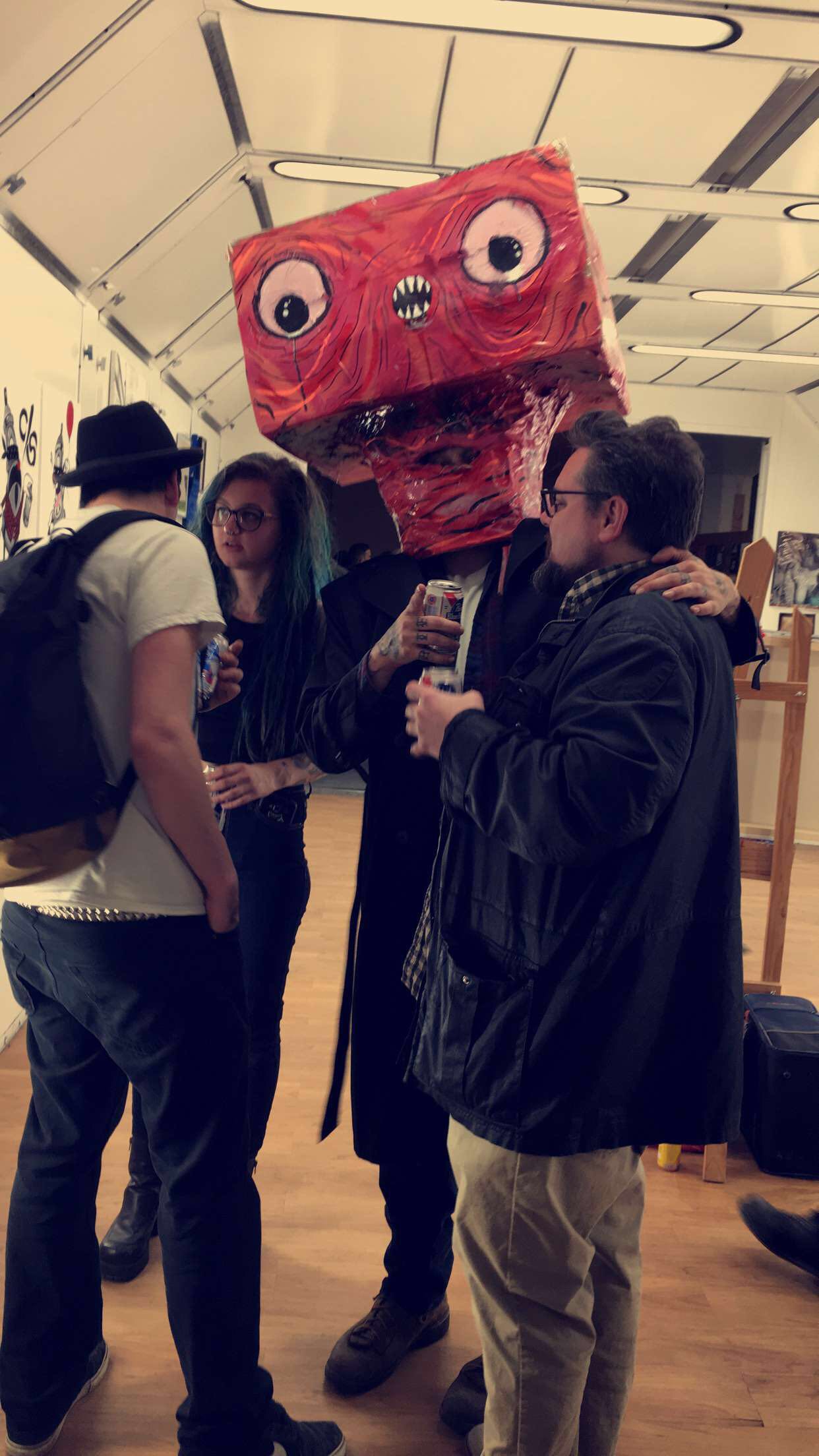

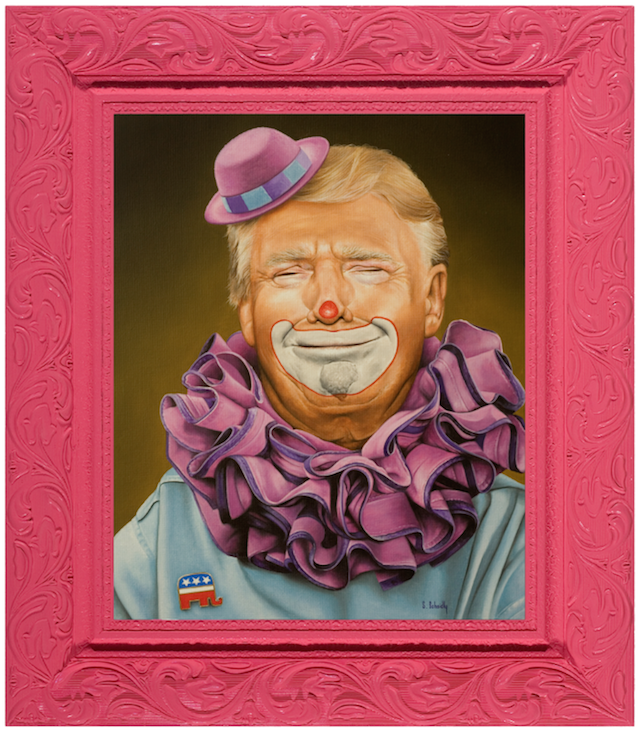

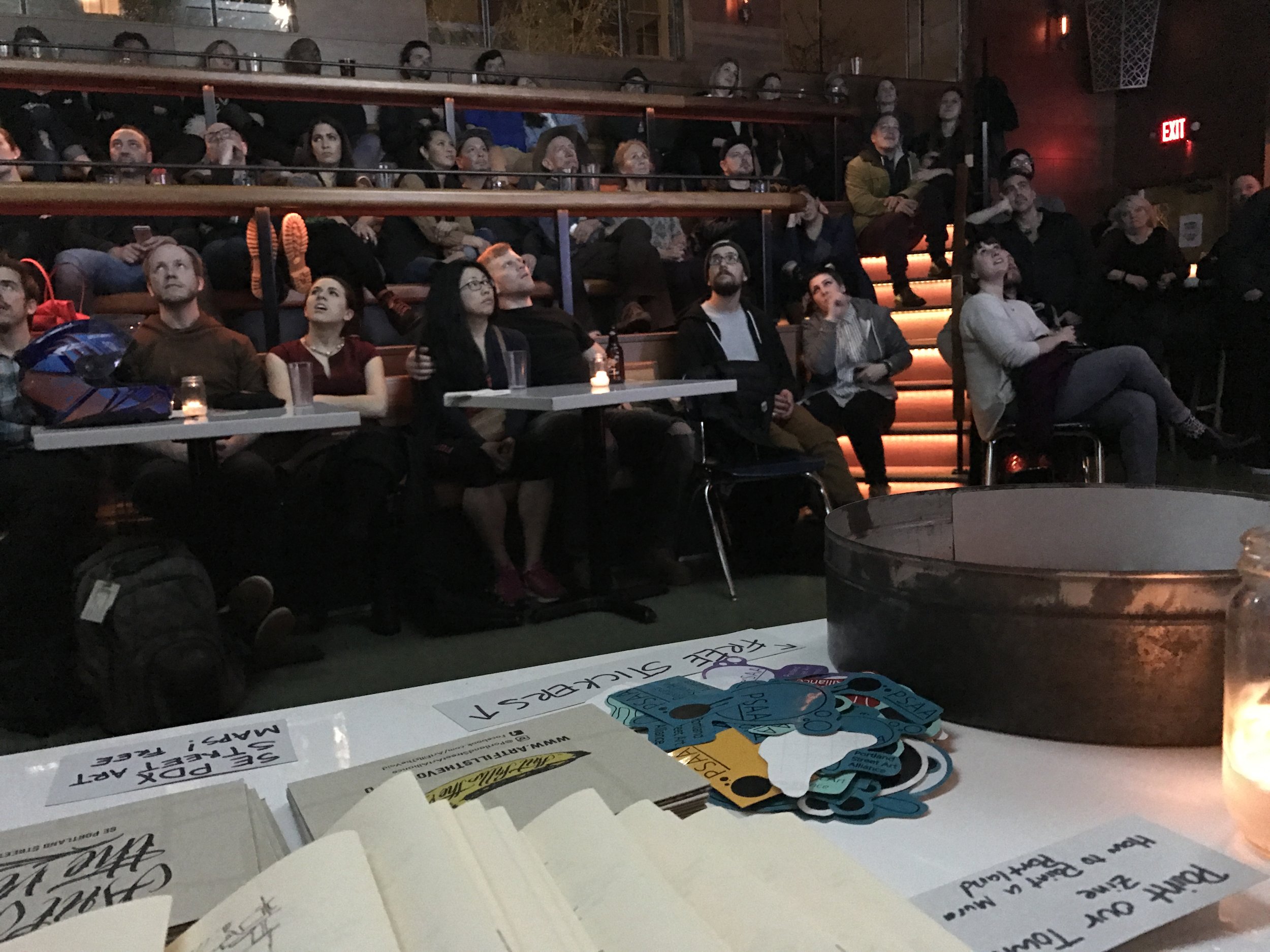

December 15, 2018 was a night to remember as Portland saw a fresh take on an exhibition, one that bring attention to the reformation and dismantling of the prison industrial complex. Jesse Hazelip - Midnite Special was held at a new art space on Failing Street, just off North Mississippi called Tips on Failing. Curated by Gage Hamilton, a renowned artist and Co-Curator and Director of Portland’s mural festival, Forest for The Trees.

Midnight Special brings Jesse Hazelip's new solo work alongside performances and collaboration with multidisciplinary artist Ginger Dunnill, lifelong friend and tattoo artist James Allison, visual artist and poet Demian Dine Yazhi, and indigo child rapper Rasheed Jamal. Each artist brought a unique voice to the show, luring audiences to submerge themselves in the essence and meaning of the artwork.

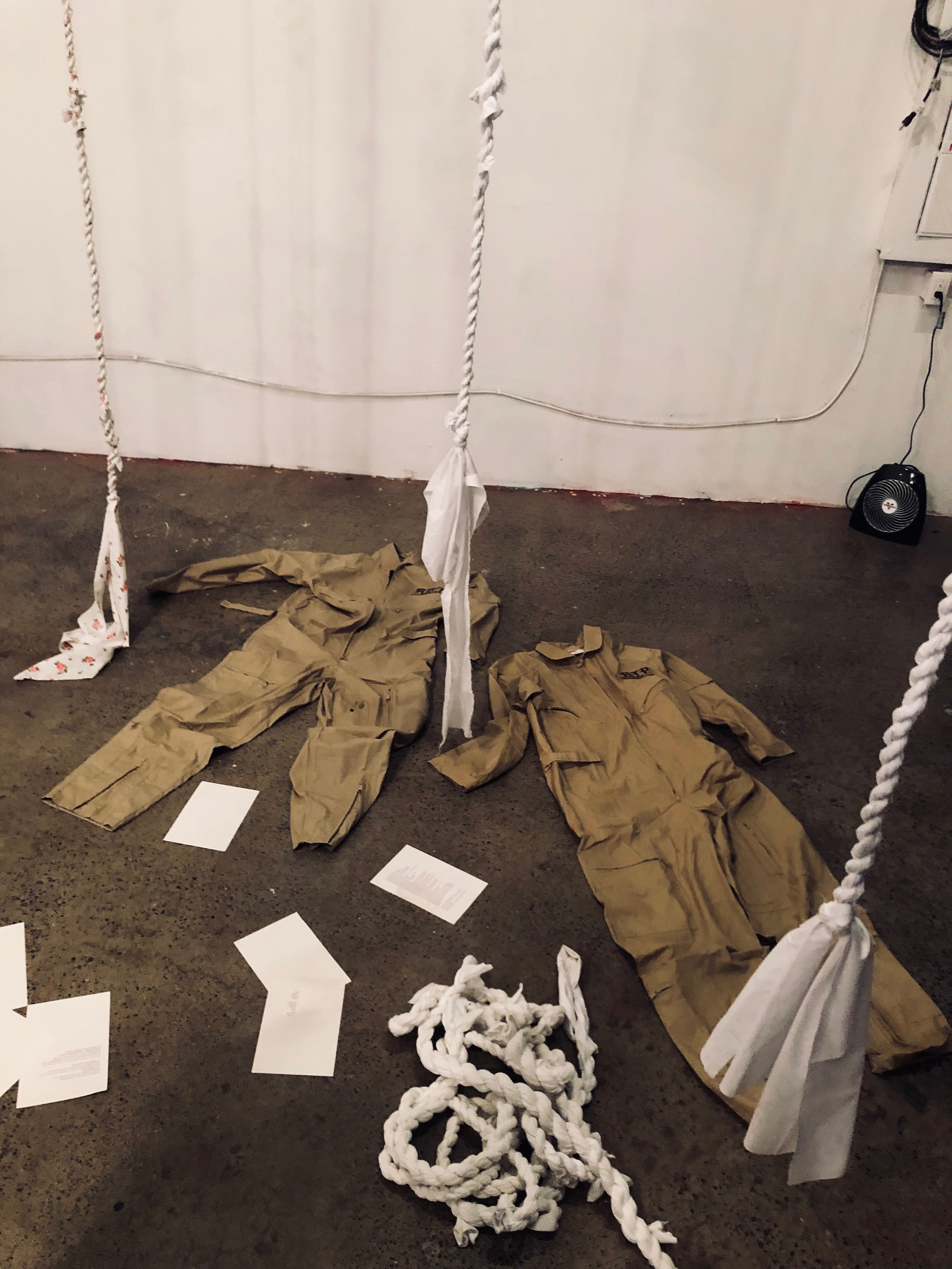

The moment you walked in, you are instantly greeted by hanging ropes made of bed sheets and the gripping sounds of ripping and tearing cloth.

"Ginger Dunnill for Mother Tongue creates a site-specific sound and fiber installation to the loving memory of all the young people of color across Amerikkka who continue to take their own lives because of the mental and physical trauma of being incarcerated" (Hazelip, 2018).

As you pass through; the ropes attached to the ceiling, hang close to the floor, leading your eye down to scattered poems, two inmate jumpsuits spread out with ropes beside them, and a sign that reads, "Rest in Peace;" instantly set the tone. The poems beautifully created by Demian Dine Yazhi, work "in an action that will embody the intention of Mother Tongue and amplify the Queer and Indigenous experience in relationship to the prison industrial complex and suicide" (Hazelip, 2018).

Walking further in, you encounter a site-specific instillation structure built to the size of solitary confinement cells in the U.S. prison system. This space creates the stage for Hazelip's live protest alongside tattoo artist, James Allison. As Hazelip sits, with his arms around his knees on the floor, sitting above him is Allison who is using a makeshift tattoo gun to tattoo a rose with a stem of rope. Intertwining with Dunill's instillation to memorialize those who have committed suicide due to incarceration. The fluorescent light shining on them, gave a sterilized glow to the room; which contrasted the white walls and grey concrete. Hazelip and Allison, collaborated together on this exhibition while Allison was still incarcerated. Both Hazelip and Allison embody true authenticity and commitment to the art and the cause.

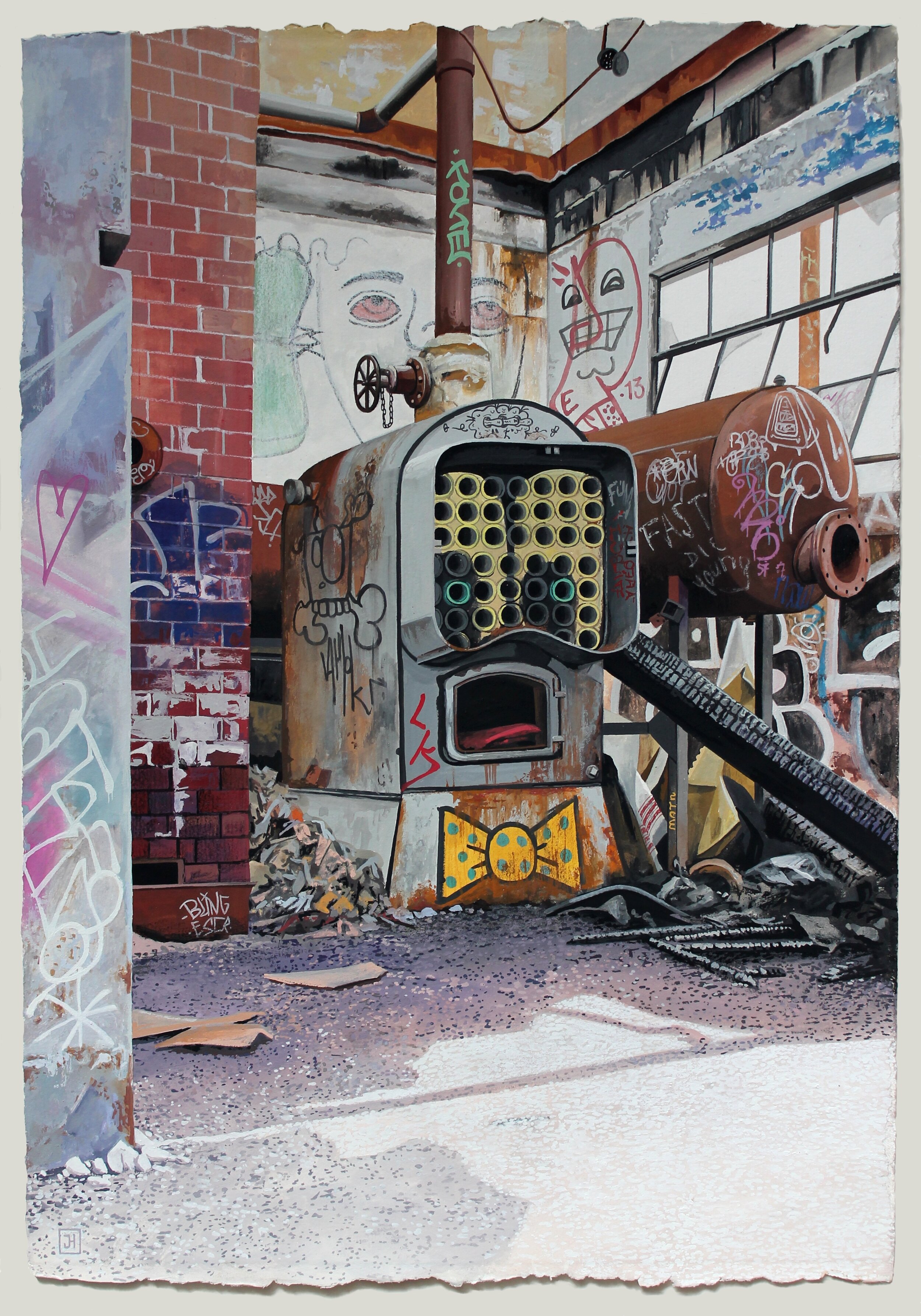

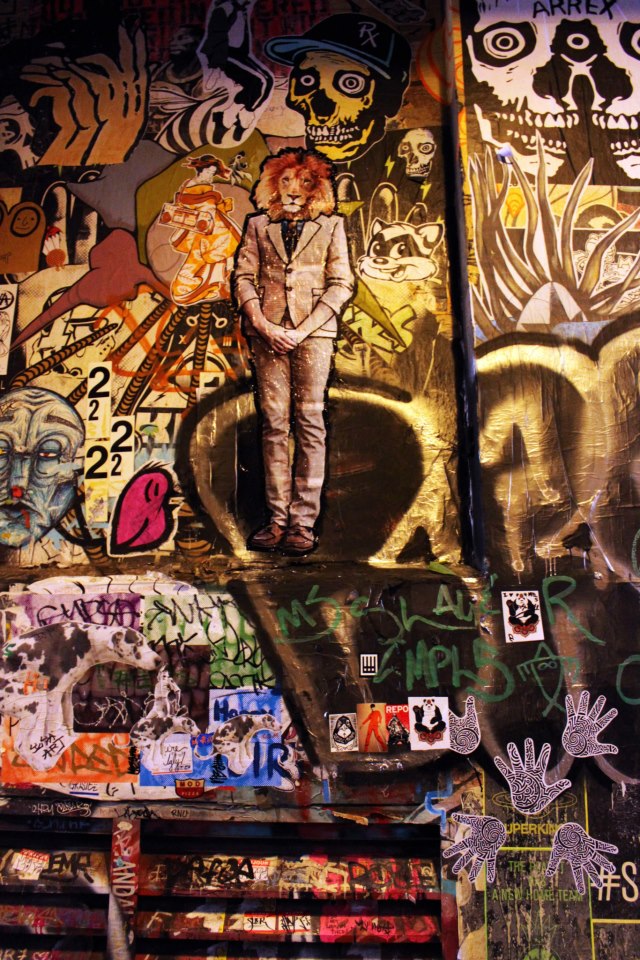

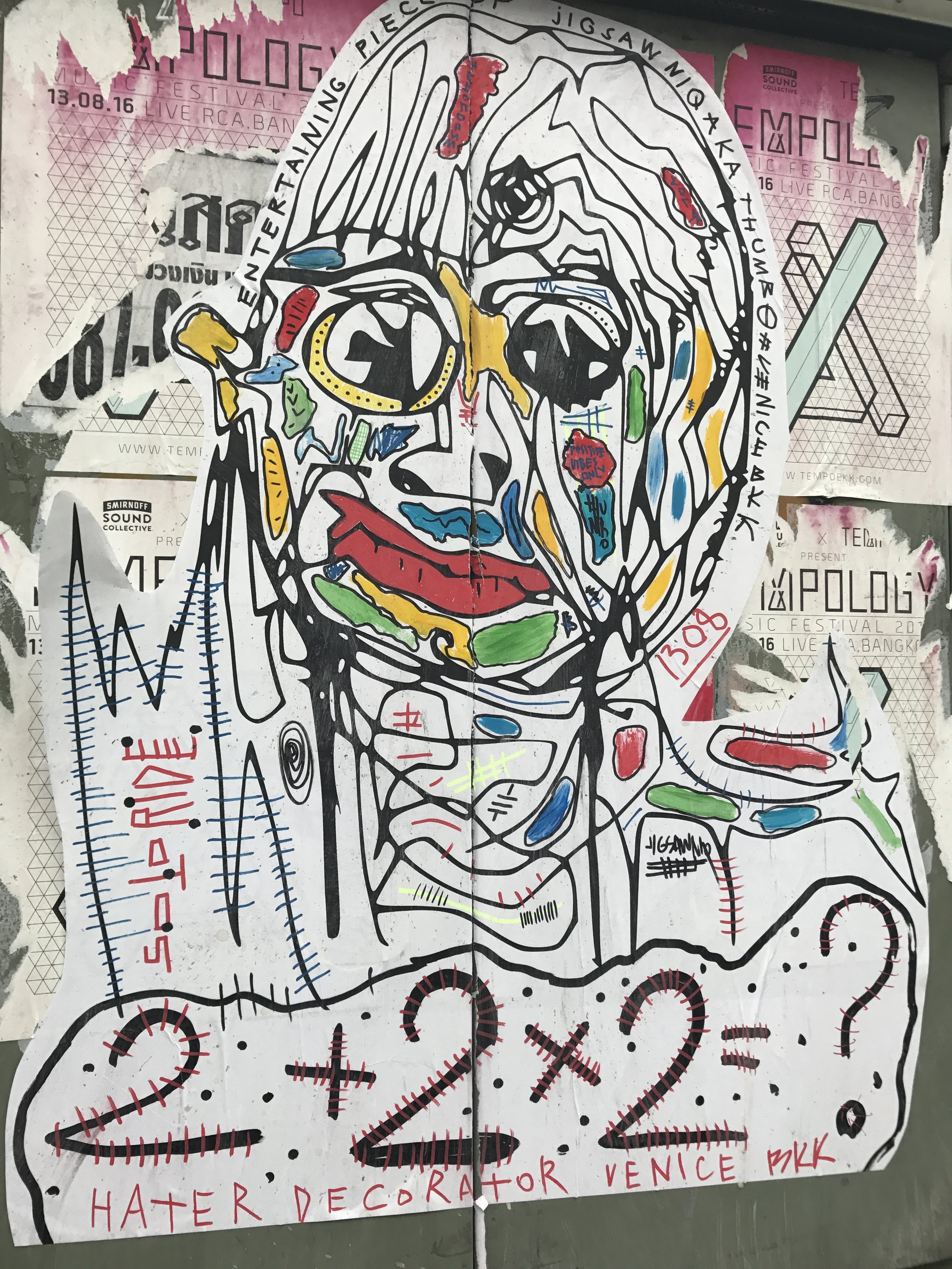

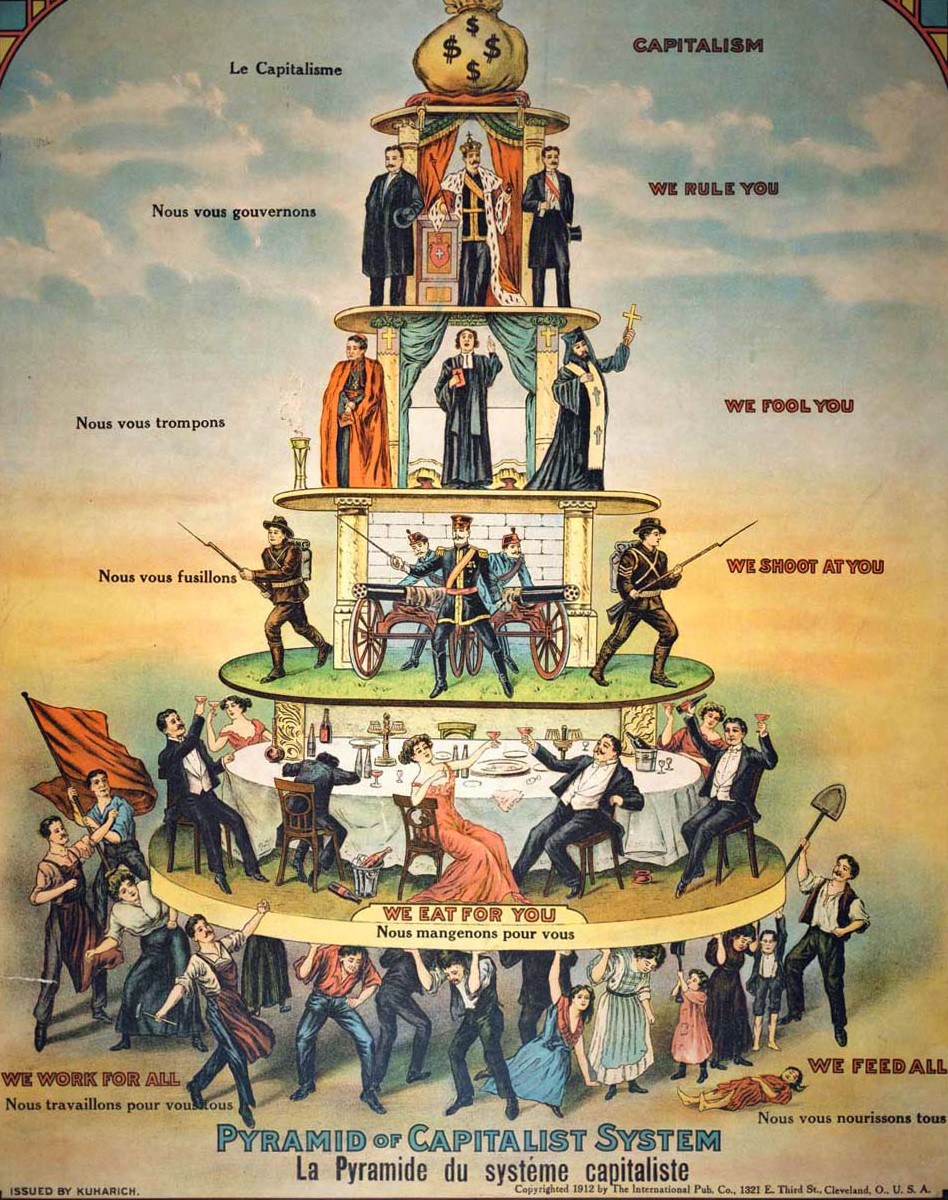

The walls showcased Hazelip’s new series, Trinity War. Hazelip interweaves three narratives: The Eternal War (the past, present, and possible future of the United States), the War on Drugs (aka people of color), and the War of Colonization (gentrification). These pieces highlighted the cause and effect of the prison industrial complex and the lives it takes. Hazelip's unique style of using fine-line ballpoint pen on paper include images of the Reaper, Bellum Se Ipsum Alet (Latin for, The War Will Feed Itself), and Coyotl. Some pieces from this series can also be seen on the streets of Portland, as wheatpasted installations.

When asked about the meaning behind his usage of three animals in his work – a wolf, bull, and vulture – Hazelip stated that when wolves are in a pack they survive, when separated and in solitude, they lose their mind. We are tribal beings. The bull is a reference to people being like cattle, with each piece already planned to cut apart. Christo, 53” x 29” (mixed media on wood) is about the “sacrifice involved in our judicial system. Our punitive approach to incarceration has been proven to be ineffective and counterproductive to the ‘sinners’. I used the back of a frame and carved out spaces for things a prisoner might want to smuggle in and hide. Blades for protection, keys for release, pictures of loved ones for comfort and an ink impression from a newborn’s feet for those mothers and fathers who can’t touch their children” (Hazelip, 2016). The hooded vulture is a reference to the situation of corruption in Rikers Island in New York.

The piece Big Skull was created out of a carved bull’s skull. The piece displays names of multiple prisons in New York City and upstate New York. “The private prison industry deals and trades prisoners as if they were livestock” (Hazelip, 2017). Each piece in his series contains personal and intimate details of an incarcerated experience, helping to heal a wound that exists in society.

Closing the show, a live performance by Rasheed Jamal gave the audience a sample of his new album entitled 22 Grams (iAMTHATiAM), which testifies to the experience of a young black male in modern day America, given from the perspective of a disembodied ‘Soul’—the main protagonist in the narrative” (Hazelip, 2018). Lyrics like, “land of the free, but I’m just another prisoner, working 9 to 5, man, it shouldn’t be so difficult” provide introspective truth and a soundtrack to the struggle of the cause (Jamal, 2018).

This deep and well thought-out exhibit curation and artist collaboration, highlights the overlapping interests of government and industry - feeding off of stereotypes of oppressed communities (people of color, the homeless, mentally ill, etc.), categorizing them as delinquents and a danger to society. Through this process, huge profits are generated by private companies, while at the same time acting to further marginalize the communities of those who are incarcerated. Due to the continuation of "tough on crime" propaganda in American culture, the larger civilian population has been tricked into believing that imprisonment is the solution to solving our social problems. As Angela Davis wrote in her essay, Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial Complex, "prisons do not disappear problems, they disappear human beings" (Davis, 1998). Midnite Special shows that our correctional institutions have turned into a “slaughter house for profit,” and we are the cattle. We look forward to each artist’s endeavors and support their courage to stand for what is right.

Citations:

Davis, A. (1998). Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial Complex | Colorlines. [online] Colorlines. Available at: https://www.colorlines.com/articles/masked-racism-reflections-prison-industrial-complex [Accessed 24 Dec. 2018].

Hazelip, J., Personal communications, December 15, 2018.

Hazelip, J. (2016, August 3), “Christo”, 53x29”, Mixed media on wood. https://www.instagram.com/jessehazelip/.

Hazelip, J. (2017, June 23), “North (Big Skull)” Carved Bull skull. https://www.instagram.com/p/BVsijzcFene/

Jamal, R, Live performance, December 15, 2018.

Sow Radical Seeds

Introducing PSAA’s newest mural, Sow Radical Seeds, at the Montavilla Farmers Market (7700 SE Stark St). This mural was designed and painted by an all-female team of artists: Girl Mobb, Sara Eileen, and Portland's own N.O. Bonzo. It depicts two strong women, sowing the seeds of radical community-driven change, nurturing a more sustainable world where communities have food security, food sovereignty, and equitable access to healthy nutritious foods. It took the artists 3 full days to complete the mural. It is the perfect backdrop to the weekly farmer’s market. PSAA has been working with Montavilla neighborhood residents and hoping to secure more walls for art in the near future.

The mural came into existence thanks to efforts by the Montavilla Neighborhood Association and PSAA. Working together in just one week they secured community-supported funding, an artist team, and a city mural permit.

PSAA, the Montavilla Neighborhood Association, and Montavilla Farmers Market officially introduced the mural to the neighborhood by hosting a community meeting where artists, organizers, and farmers came together to talk about how they sow radical seeds in the community with the work they do.

At the meeting, Javier Lara of Anahuac Produce spoke about his work as a farmer, community leader and activist for human rights. His philosophy on farming stems from a deep connection to nature, and his practice mimics those beliefs. Javier says farming is “more than just local or organic, it has to do with community, and human beings are part of this system.” Javier also fights for farmworkers’ rights as well by working in partnership with PCUN-Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (Northwest Treeplanters and Farmworkers United). PCUN is Oregon’s farmworkers union and the largest Latino organization in the state.

Lily Matlock of Lil' Starts also spoke at the meeting about her 2-acre urban farm located in the East Columbia neighborhood of NE Portland. Lil’ Starts uses permaculture and biodynamic principles to grow clean, healthy produce and robust productive plant starts for local farmers markets, restaurants, and their two CSA programs.

This mural and community meeting was an opportunity to meet people who are sowing radical seeds in Montavilla, and soak up some inspiration for your own community good works!

Please consider donating to this project, to show your support for the artists time and creativity! So far we have raised just enough to cover supplies and the city mural permit, but we also want to try to compensate the artists for some of their donated time: https://www.gofundme.com/sow-radical-seeds-mural

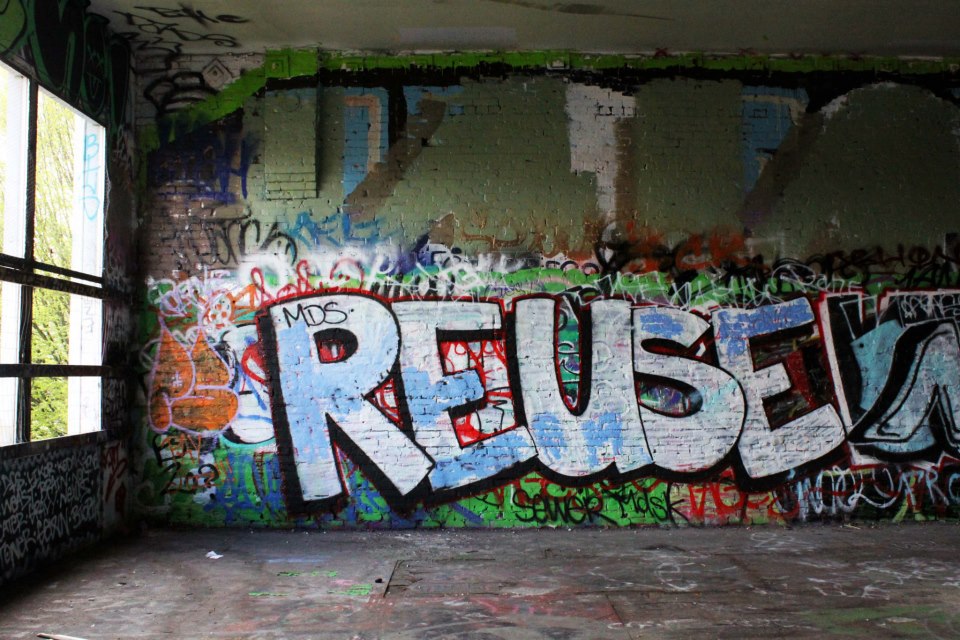

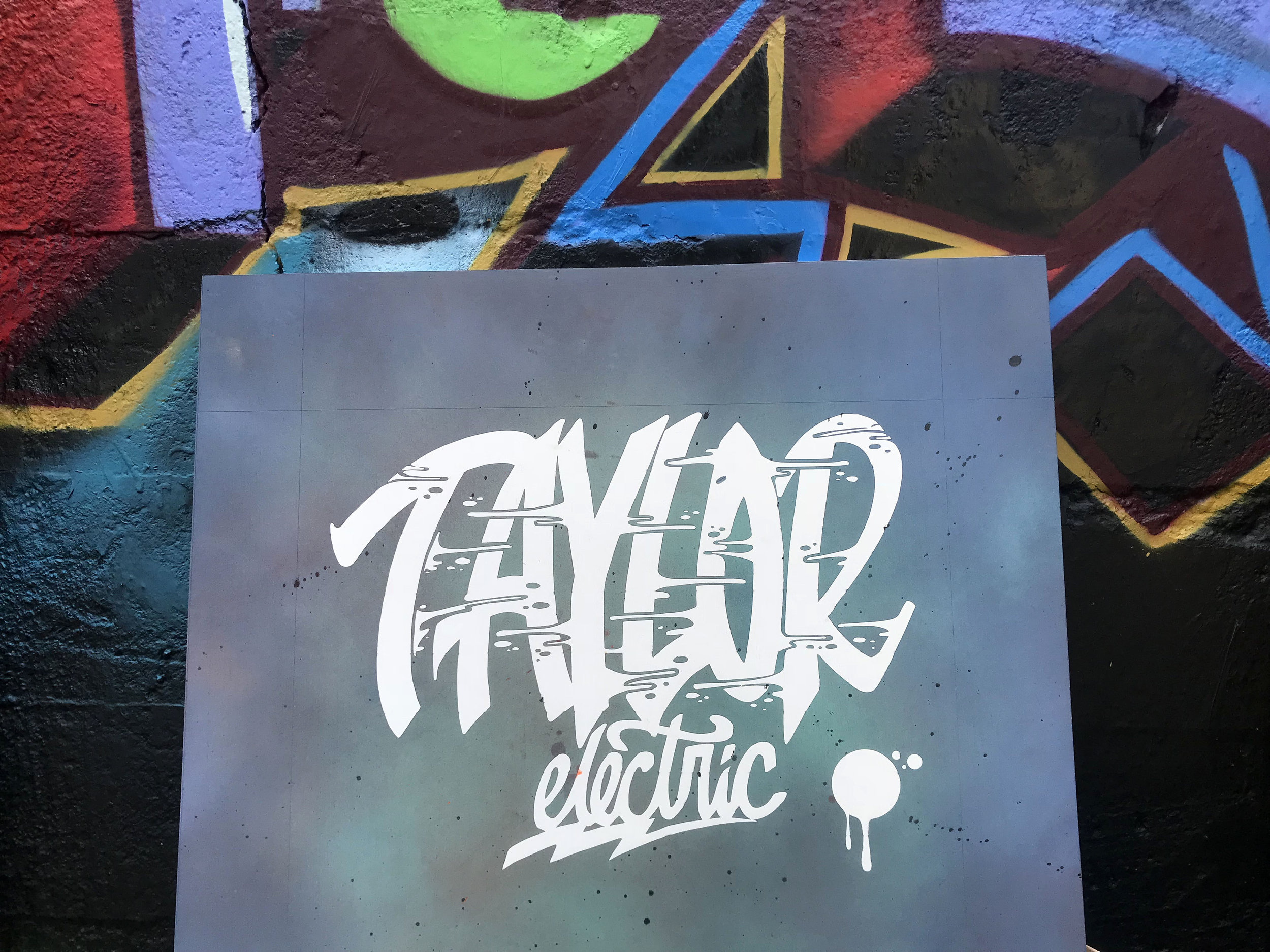

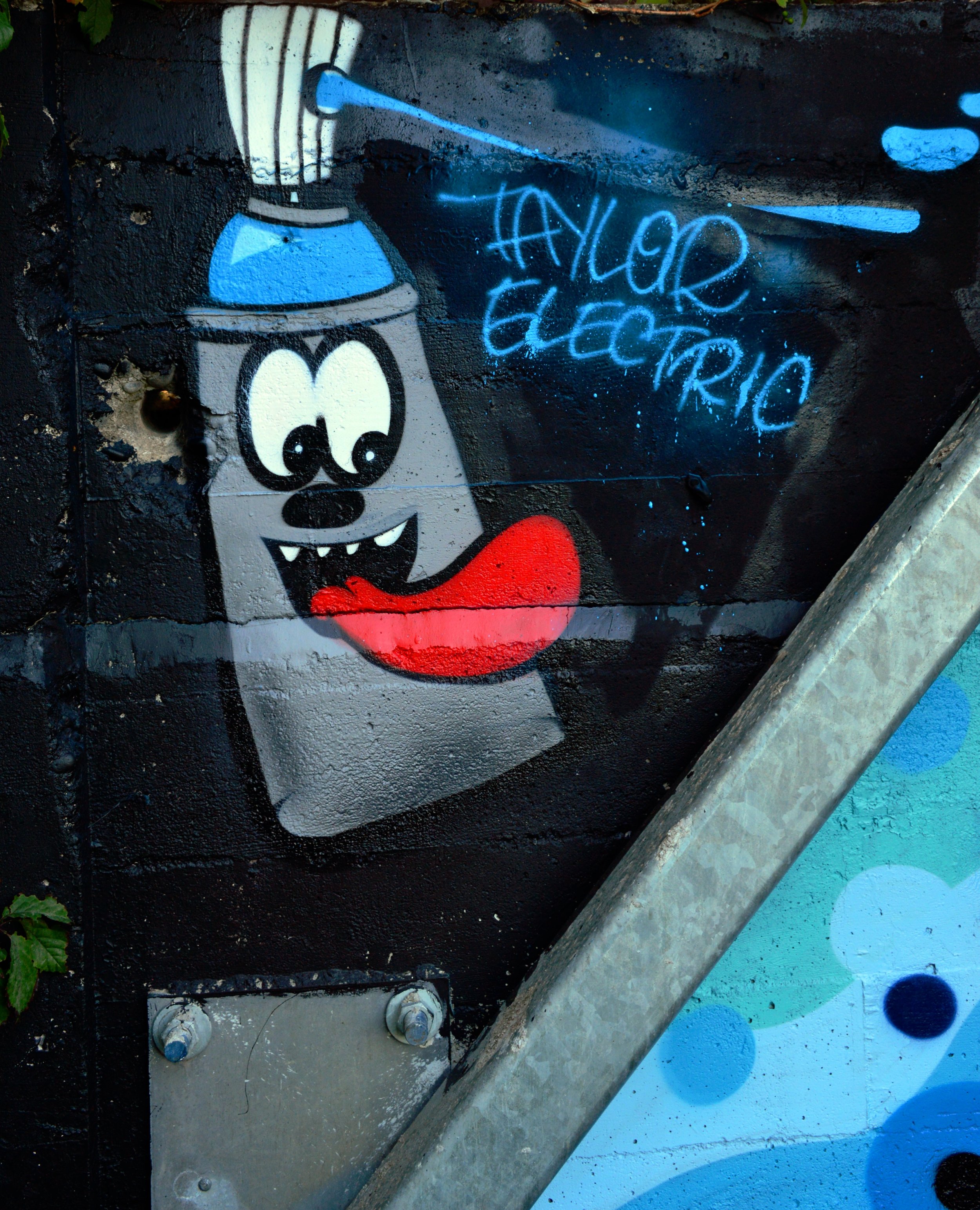

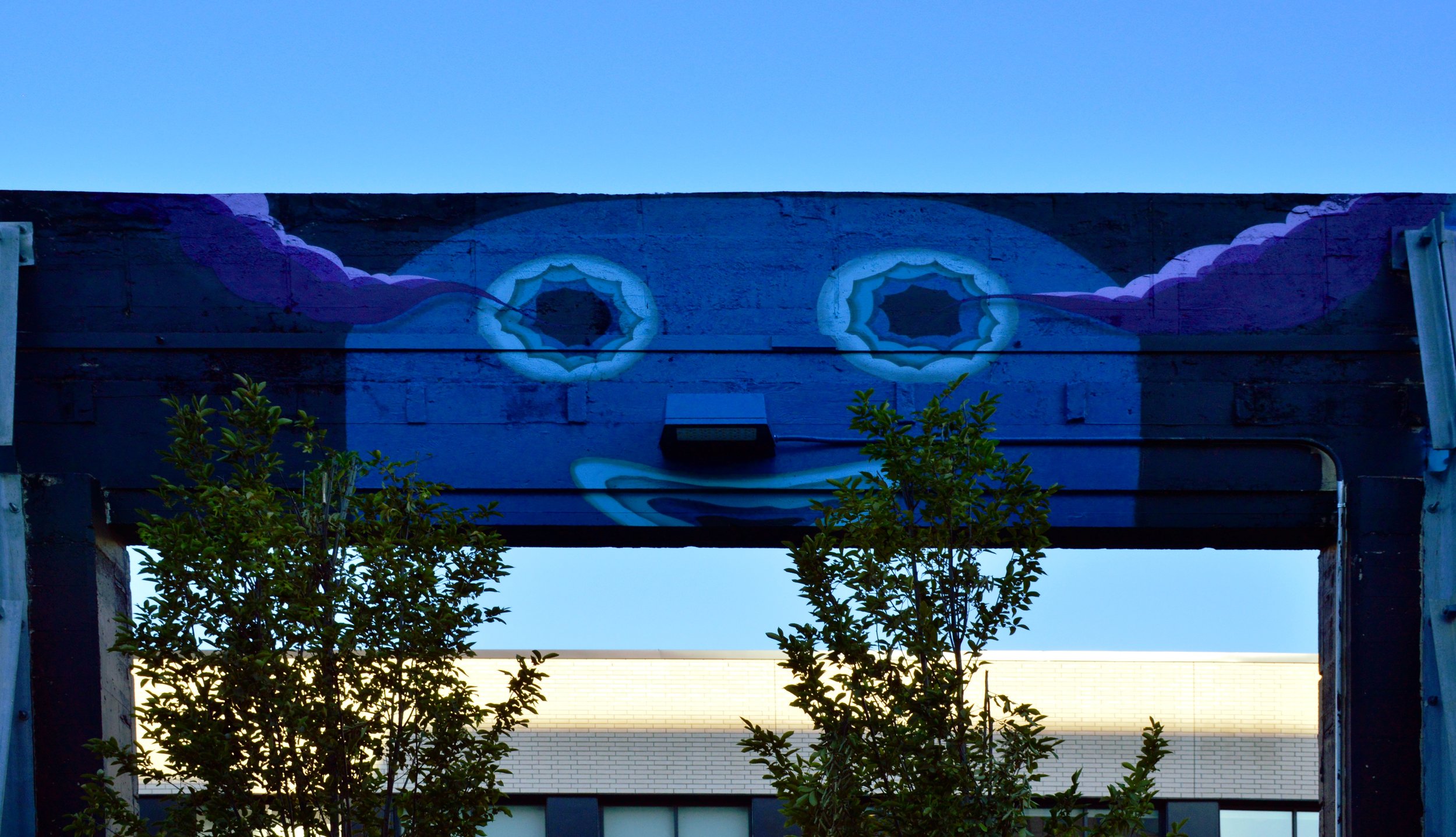

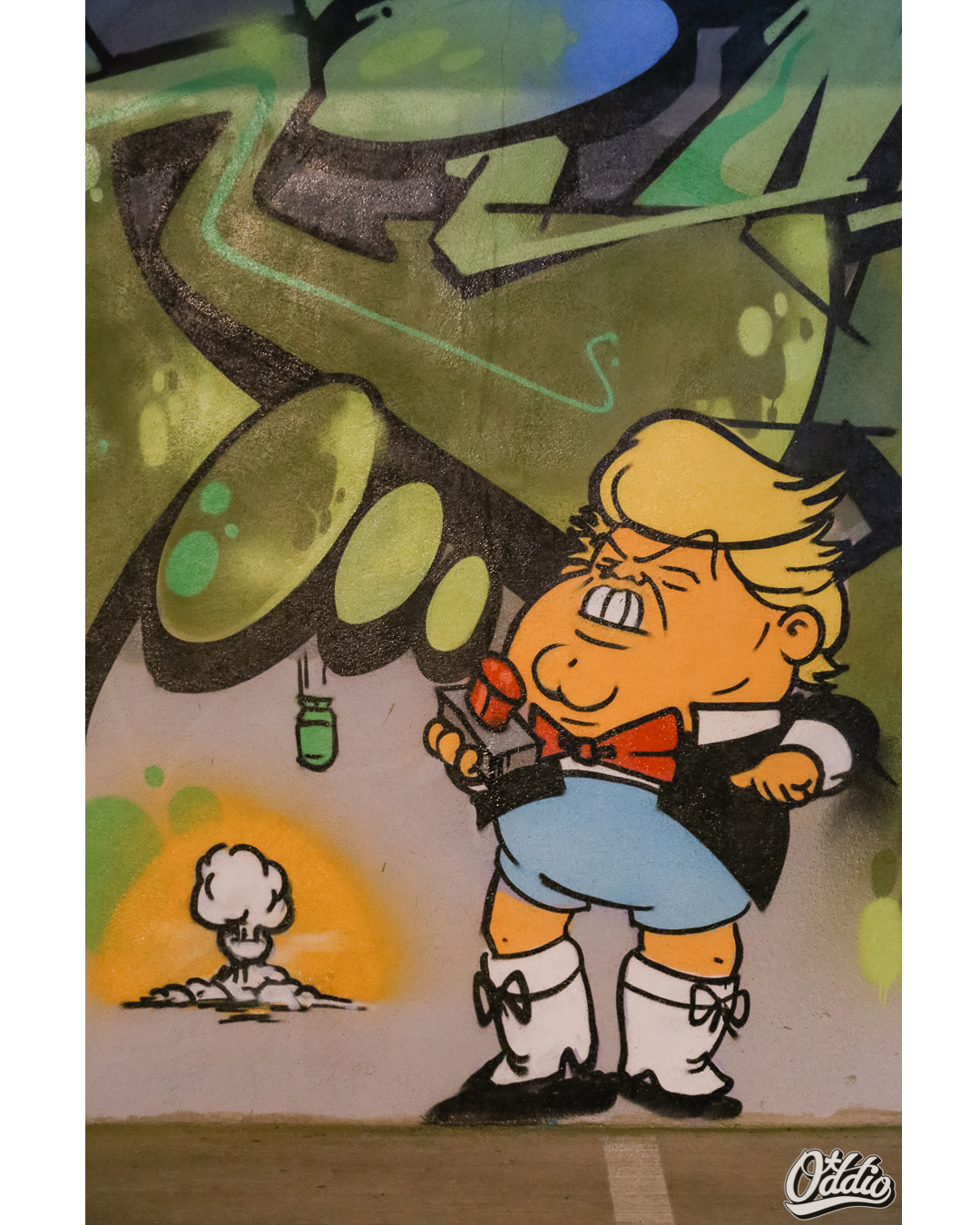

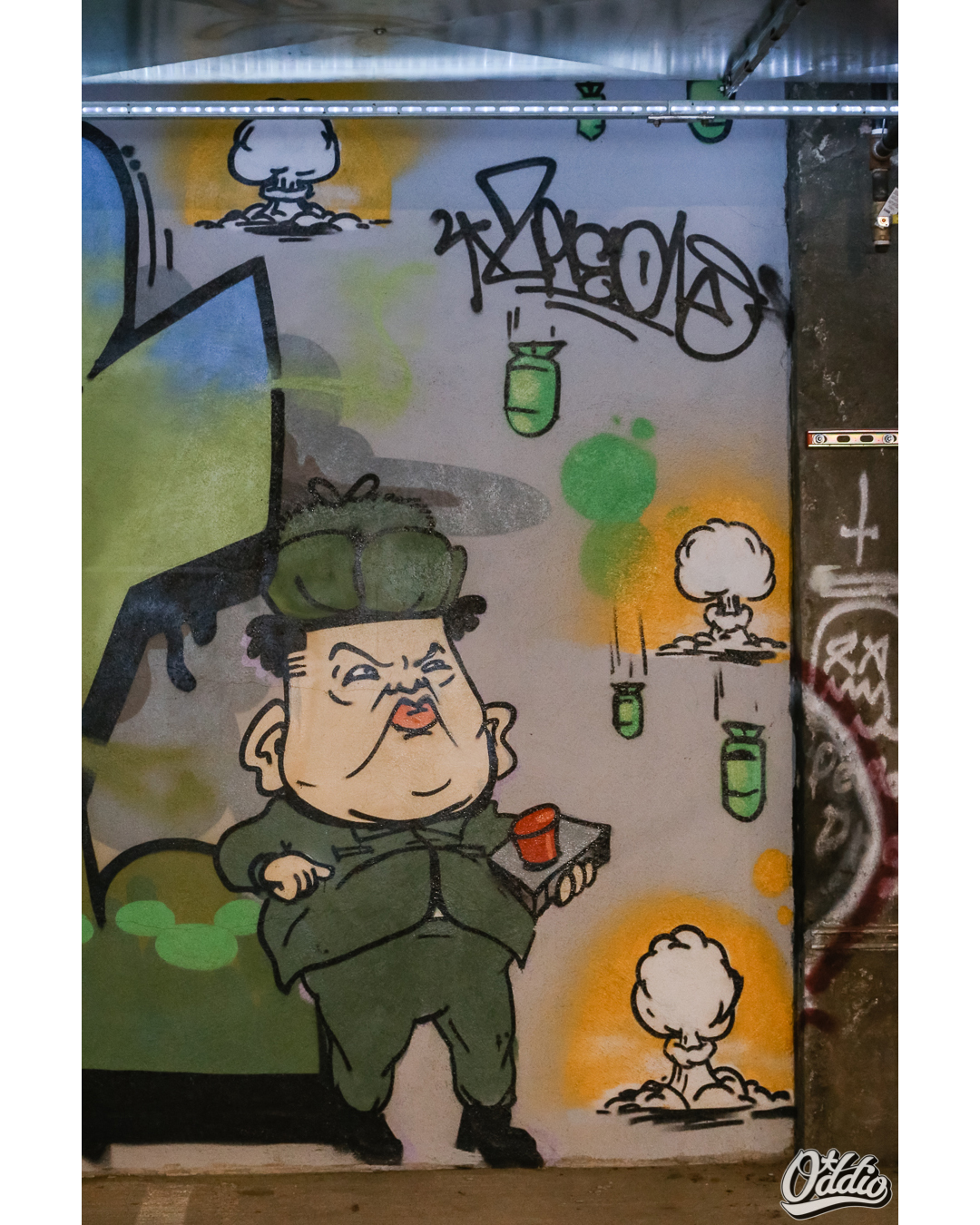

Taylor Electric Project

The Taylor Electric Project at the Electric Blocks, is a collaborative, open-air street art gallery that features the work of over 100 artists. For over a decade, the ruins of the Taylor Electrical Supply Company, located on 240 SE Clay St., became a Portland nexus of local, regional, and national graffiti and street art following a fire that left only the burnt-out husk of walls, a perfect canvas for street art within Portland’s ever-changing Central Eastside District. In 2015, what remained of the building was demolished but with the support of Killian Pacific, Portland Street Art Alliance is collectively rebuilding the Taylor Electric Project into a haven for street art once again. Portland Street Art Alliance manages the painting at Taylor Electric and in 2018 co-hosted an all-day all-ages event with the help of For the Love that includes live-paintings, artist commissions, live music, a dance battle, local pop-ups, food carts, local beer, skateboarding ramps, and more. Thousands of people come out to celebrate Portland’s vibrant public art communities. The annual block party is truly a DIY community-centered and driven event, made possible with the support from local sponsors, volunteers, and artists.

2018 Block Party Recap

BLOCK PARTY NEWS COVERAGE

HISTORY OF TAYLOR ELECTRIC

For over a decade, the burnt-out ruins at SE 2nd and Clay served as Portland's most famous space for graffiti– a free open art gallery that attracted artists and onlooks from near and far.

Built in 1936 by the Loggers & Lumberman’s Investment Company, the warehouse at 240 SE Clay (previously 352 E Clay St) served as a home to many different businesses through its lifetime at its picturesque location at the east-end of the Central Eastside Industrial District. In the 1990s, the Rexel Taylor Electrical Supply Company purchased the building and used it as a storefront and warehouse for electrical supplies.

On the night of May 17, 2006, a stack of pallets outside the building caught fire. Fueled by the electrical supplies inside, a massive 4-alarm fire broke out. Over 125 fire-fighters from Portland and nearby cities worked around the clock trying to extinguish the blaze and protect nearby buildings. Burning for over 24 hours, the fire sent a river of debris into the nearby Willamette River.

Taylor Electric Fire on May 17th, 2006. Images courtesy of Greg Muhr (@911firephotg).

Taylor Electrical Supply had plans to rebuild and sell the property, but that fell through, so the charred skeleton of the warehouse sat abandoned for over a decade. The ruins blossomed into a unique and iconic local landmark - a sanctuary for artists, rebels, and outcasts. When people visited Portland and wanted to see graffiti, Taylor Electric was an obvious and easily accessible destination. Cultural activities from dances, circuses, and bicycle chariot wars used Taylor Electric as a gritty stage and backdrop.

In many booming west coast cities, space for unanticipated interactions and unauthorized art are rapidly diminishing. However, these derelict spaces serve important functions for many creatives. Artists are often some of the first to find, occupy, and re-use dilapidated spaces. These cracks of the urban fabric fall outside the watchful eye of neighbors and police.

There is an inherent uncertainty and unpredictability of abandoned spaces where graffiti often gravitates. These spaces often provide the raw material conditions that incubated new ways of expression and imaginative thinking. Graffiti’s ephemeral and nomadic nature contributes to its resiliency and allure. For these reasons, the aesthetics of Taylor Electric were addictive for many, including artists, tourists, academics, journalists, photographers, and videographers. Geographer Bradley Garrett wrote: “These spaces are appreciated for their aesthetic qualities, for their possibilities for temporarily escaping the rush of the surrounding urban environment and their ability to hint at what the future might look like, when all people have disappeared, a visceral reminder of our own mortality.”

Taylor Electric Inspired Artwork by Brin Levinson.

Taylor Electric Inspired Artwork by Jessica Hess.

Rumors of demolition and redevelopment plans of Taylor Electric had been circulating for years. With Portland’s booming economy and population this change was inevitable. As power and urban space collide, developers inevitably would redevelop this centrally located property. A family-owned local development company, Killian Pacific eventually purchased the property intending to develop it into a new office campus called the Electric Blocks. Thankfully, Killian Pacific appreciated the cultural history and raw beauty of the space and decided to preserve and reinforce part of the old south-facing retaining wall, incorporating it into the new building.

In the months leading up to its demise, the art at Taylor Electric flourished as the fences went down and security was reduced. More so than ever people of all types, young and old, high heels and rubber boots, descended on this public place to experience a post-apocalyptic scene bursting with color.

On May 10th, 2015 the demolition of Taylor Electric began. Spreading quickly through social media, artists shared images of the first walls to fall. Some onlookers talked with workers, gathering details of the plans. Local media outlets covered the demolition, focusing on the cultural importance and impact of this space.

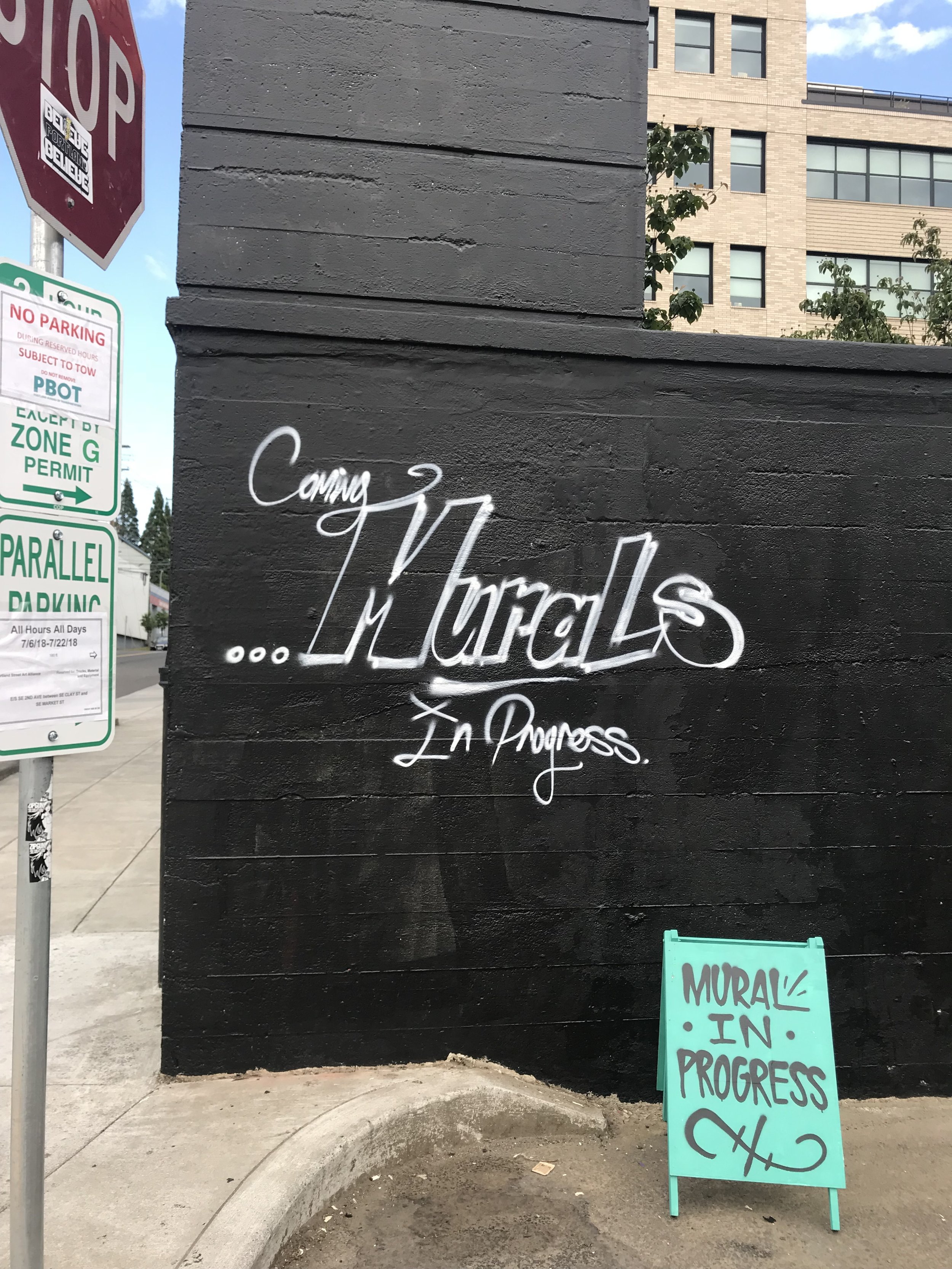

While a sense of loss pervaded, there was also a sense of unity and reflection that arose, as many people began to introspectively think about what was being lost, but also what had been built over the years in this space. During this time, the Portland Street Art Alliance (PSAA), a local arts non-profit that advocates for and manages street art projects in the pacific northwest, started pitching the ideas of hosting a gallery art show in commemoration of the old space. Donations immediately started coming in from community members and businesses. PSAA connected with Killian Pacific and the main tenant of the building, Simple Bank. From these new partnerships, a new idea was born – bring graffiti art back to the site, but this time, provide artists time, structure, and funding to really make a huge splash. The collective aim was to honor and continue the history of this unique art sanctuary. To create a new rotating public art gallery displaying fresh works from pacific-northwest and visiting artists.

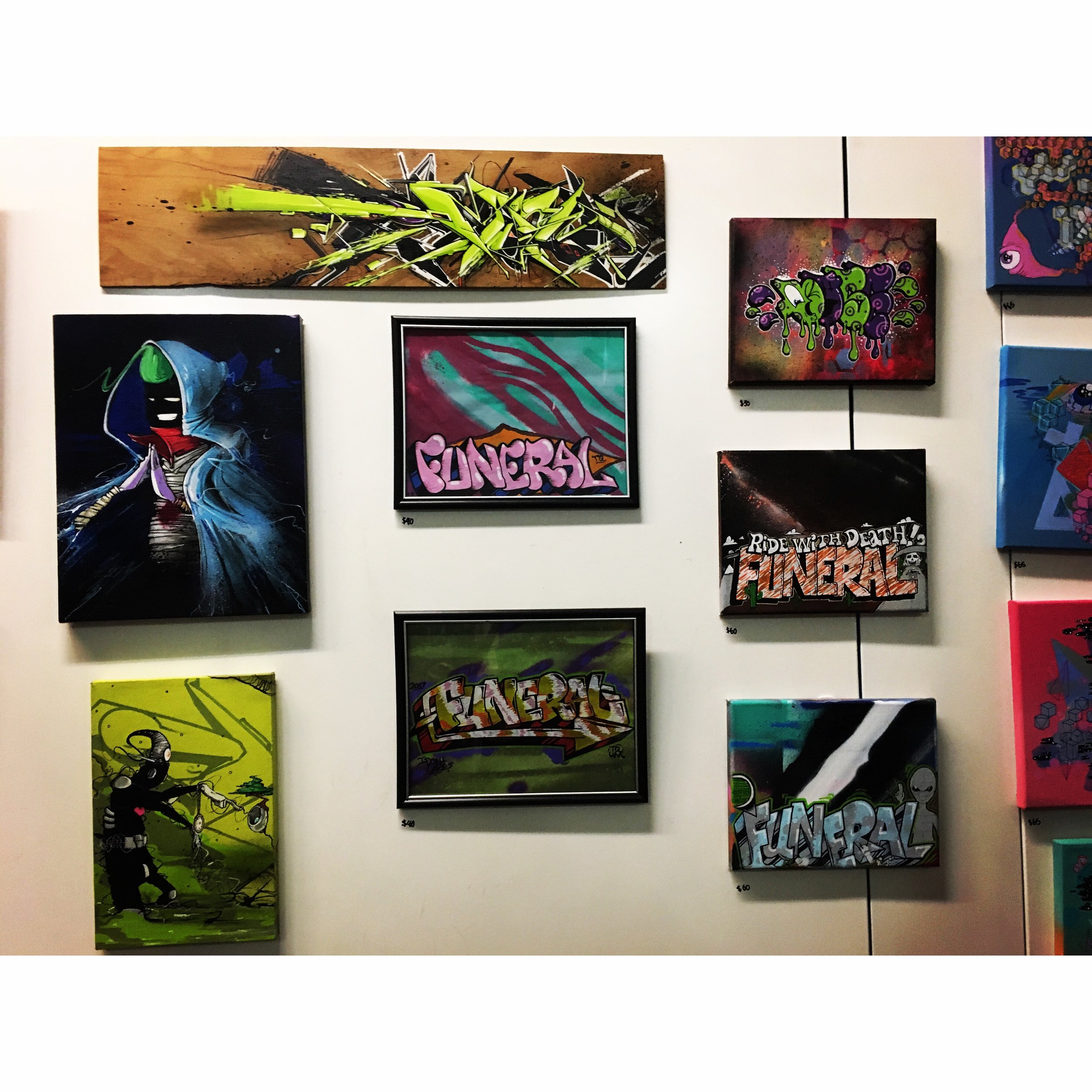

Since 2017, the Taylor Electric Project has been managed by PSAA with support of Killian Pacific and local businesses. Over 150 regional artists have painted murals at the site, completely covering the underground garage and old remaining walls of the warehouse. Fresh artwork is happening all the time.

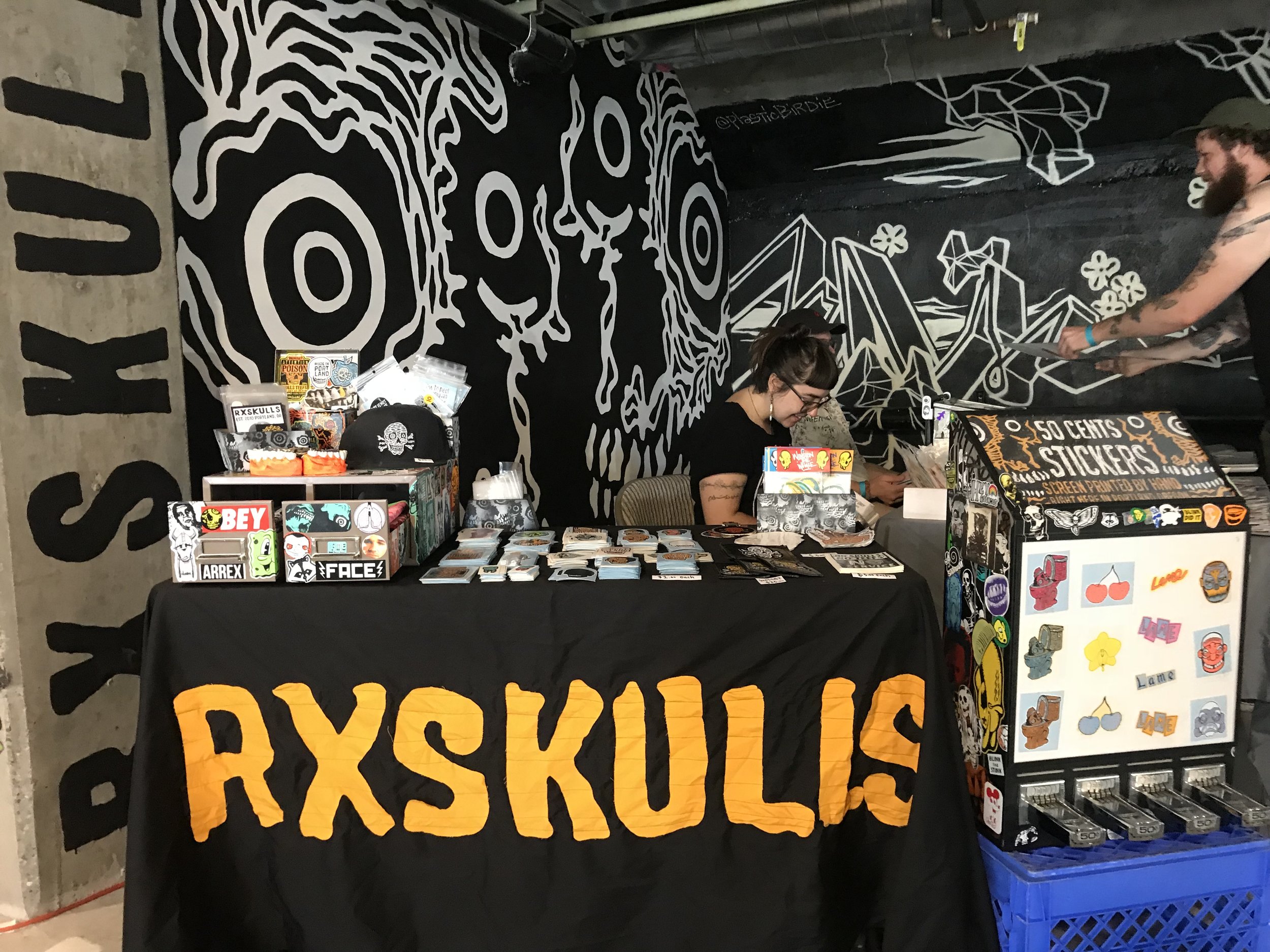

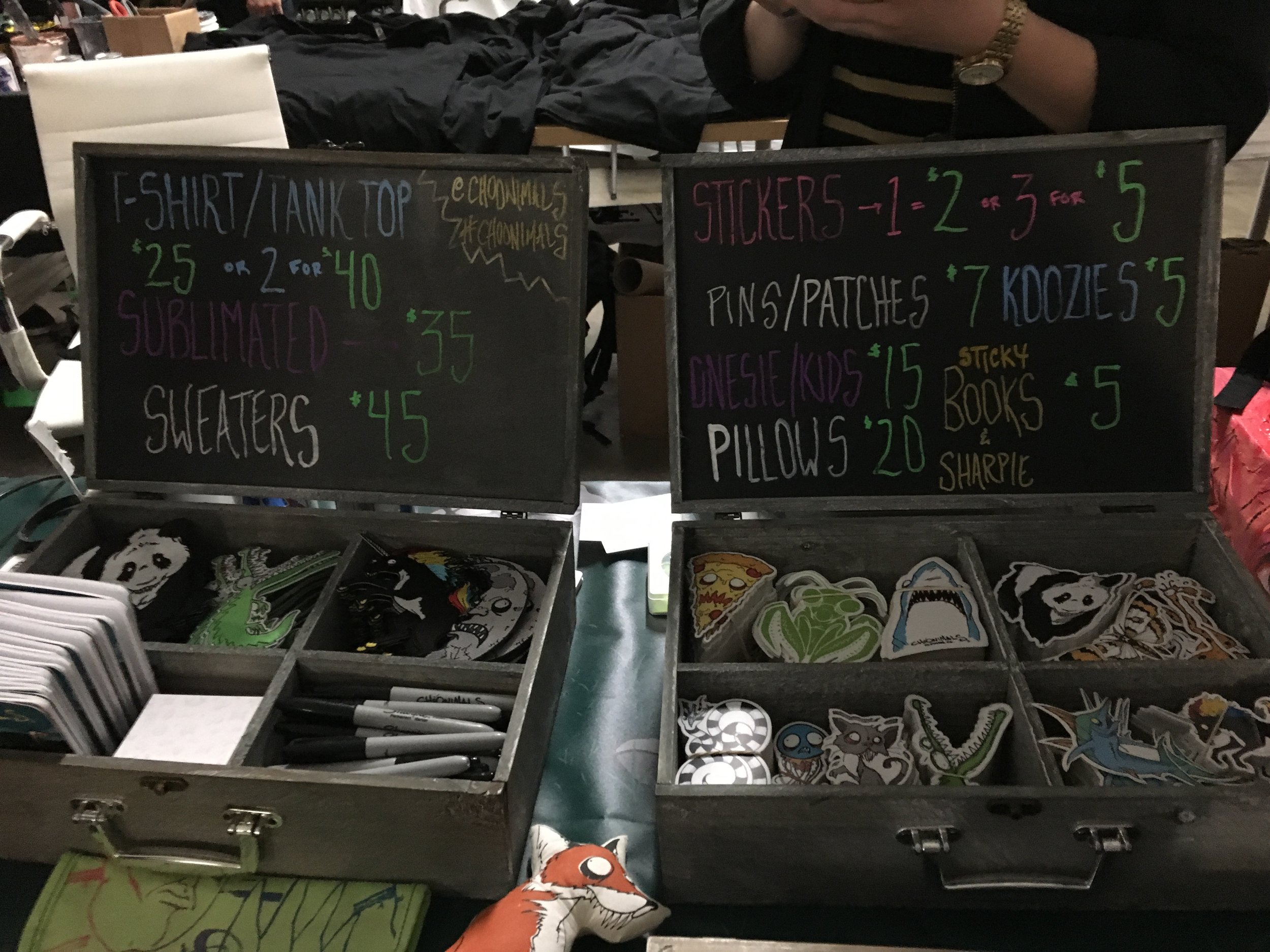

On July 21st, 2018, PSAA organized a team of Portland-based artist collectives to co-host a huge block party. Over 2,000 people came to celebrate the completion of the new murals. The block party had live painting by over 20 artists, live bands, a dance battle organized by Find a Way, a pop-up skate park erected by D-Block, kids activities, a food and beer garden, and an art fair in the garage where local artists sold merchandise and did live screen printing.

Portland Street Art Alliance plans to host the block party event again, bringing together artists from around the Pacific Northwest to celebrate and further seed art in the new Central Eastside Mural District and beyond.

READ MORE ABOUT TAYLOR ELECTRIC

INTERIOR MURALS AT THE ELECTRIC BLOCKS

Working in partnership with Killian Pacific and Simple Bank, PSAA has managed several interior office mural at Clay Creative, with plans for more. The aim is to provide local artists access to commission opportunities, and provide workers with an inspiring everyday environment to be in, in the heart of Portland’s Central Eastside Industrial District.

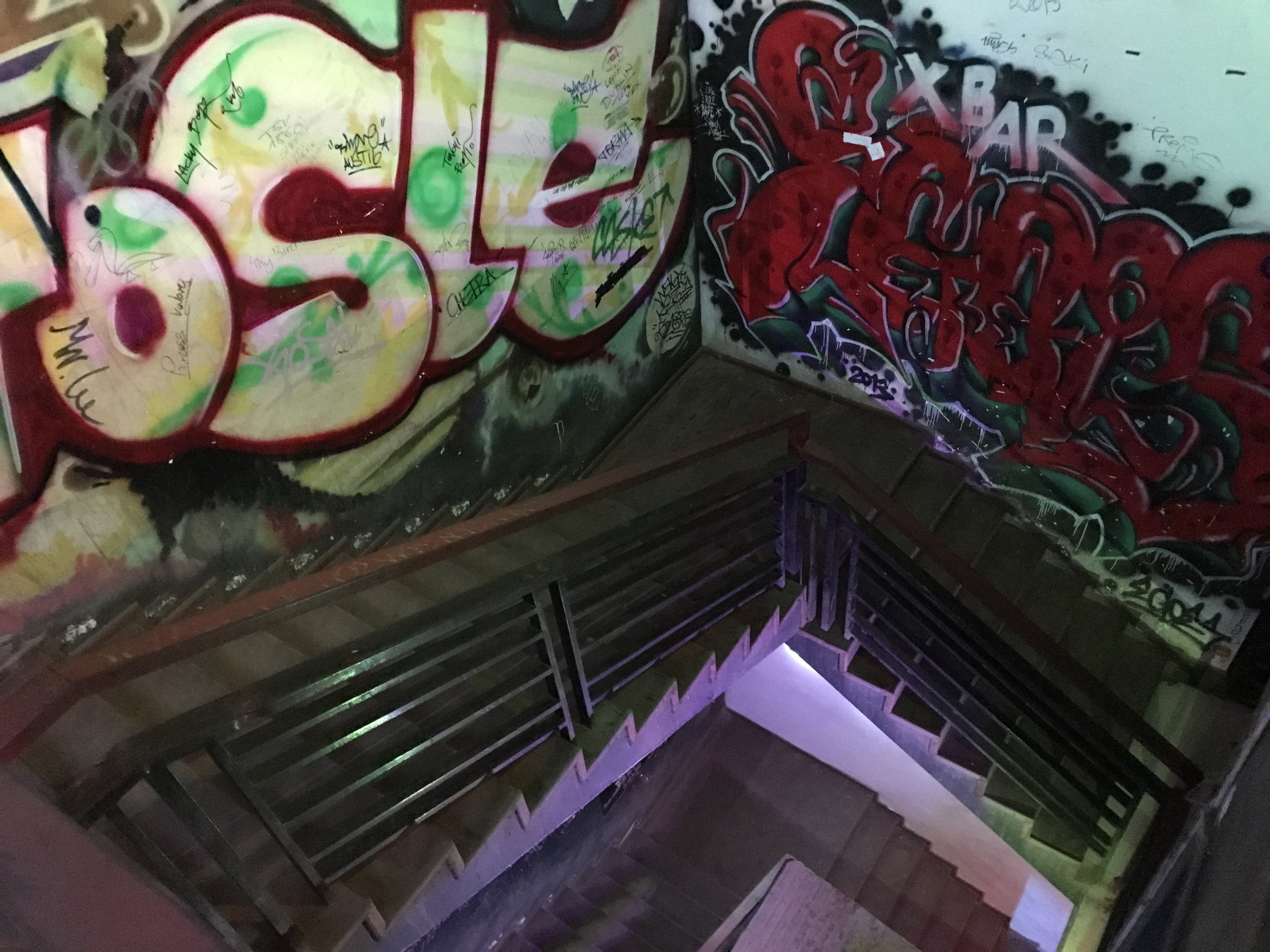

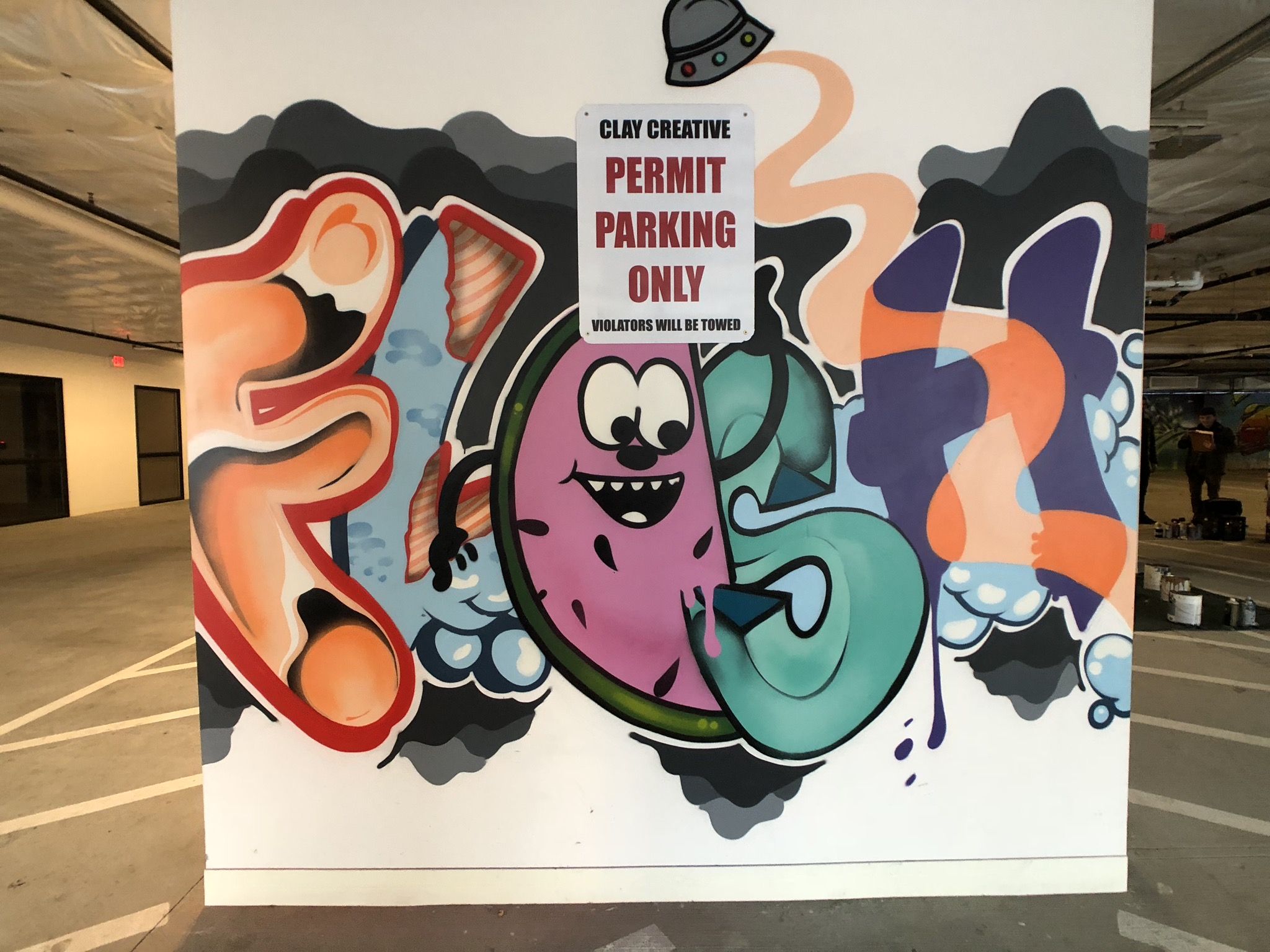

THE NOVA GARAGE

In 2017, PSAA began organizing rotating painting inside the parking garage at Nova. All garage murals are done on a volunteer basis by both PSAA and participating artists. These walls provide much needed space to build portfolios, experiment with new designs, and painting techniques. The garage has become a true community space, an ever-changing art gallery, and space for gathering and activation.

![IMG_E3155[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422463076-I80S072851Q1AOE3QO2N/IMG_E3155%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_E3154[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422471722-84M1WK0LJYBBLSAJFI2W/IMG_E3154%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_E3153[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422479156-GRLX10TIJQ0TYX3DQIXS/IMG_E3153%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_E3152[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422495470-OCPRFUPII4WCBQCFGUSK/IMG_E3152%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_E3151[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422501581-QWOP17N6HI3BU3023EN9/IMG_E3151%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_3158[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422507347-IN63252D6V6CCDKKSBJF/IMG_3158%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_3157[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422518114-S8P1TQUSUC7SH9OL2KCF/IMG_3157%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_3156[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422530046-19WA4BYRXH3POQ689OMT/IMG_3156%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_3036[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422566104-OG2X5SNC0513K7U1NSU3/IMG_3036%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_3097[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422596251-WVP89R34PV8OFKI98HHA/IMG_3097%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_E3167[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422759806-N06U0I4AVJ6HQ3F7EGD1/IMG_E3167%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_E3166[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422768969-T009CJPK22ICXTREH5IM/IMG_E3166%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_3163[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422791241-R5KJM4Z6POKT4X6M4RG3/IMG_3163%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_3161[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422802945-BUQO11HLI4CBNCAA63KA/IMG_3161%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_3160[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1521422815687-KYQC292C03KVM4AT29K2/IMG_3160%5B1%5D.JPG)

© All photos copyright of credited owner. Do not use without permission.

Cover image by Crystal Amaya. All rights reserved.

Sponsors & Partners

The Central Eastside Mural District is funded, in part, by the Regional Arts & Culture Council, Prosper Portland, the Oregon Arts Commission, and the Central Eastside Industrial Council’s Central Eastside Together grant program.

Keep on the Sunnyside

KEEP ON THE SUNNYSIDE

PORTLAND, OREGON

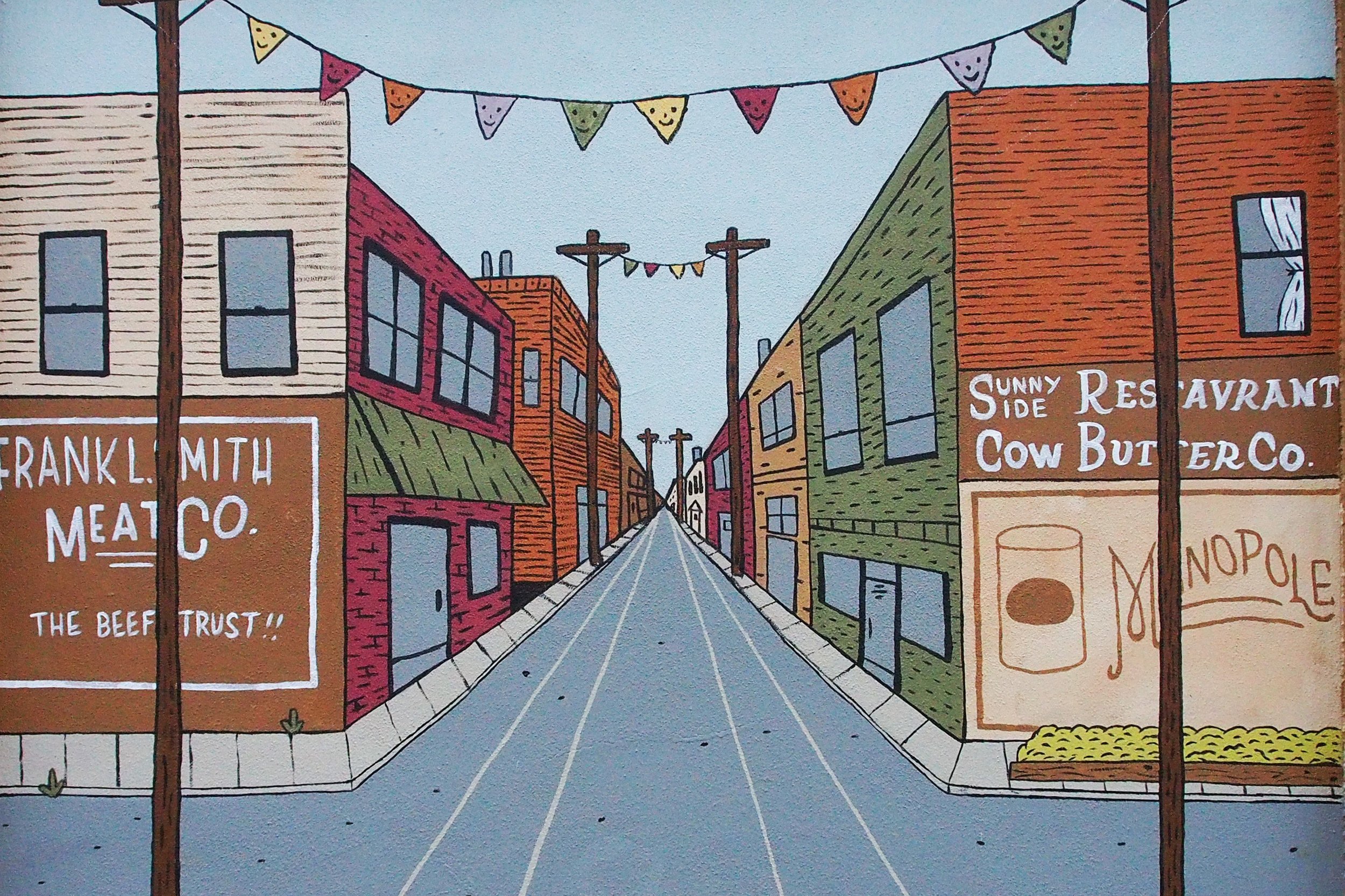

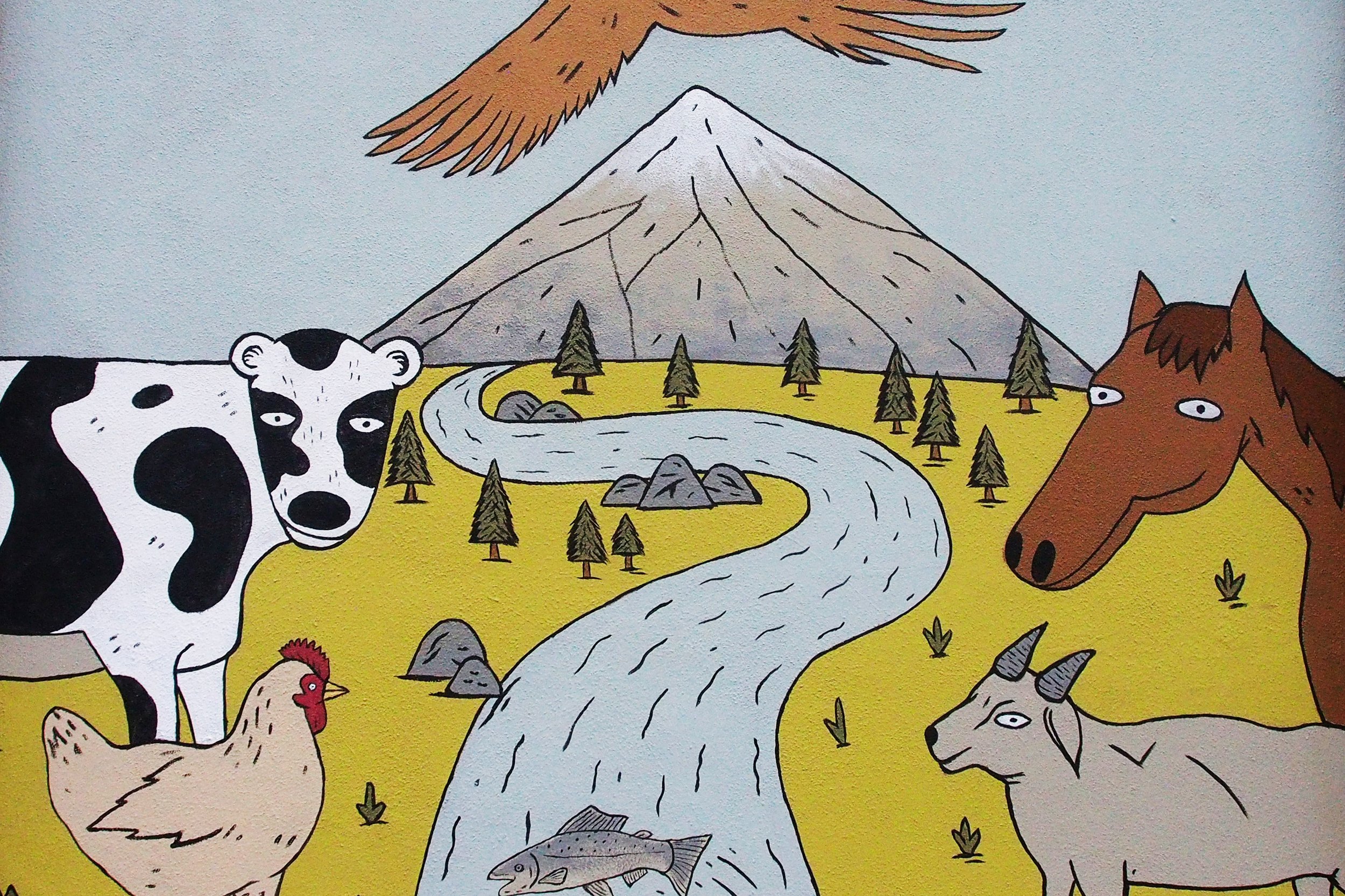

KEEP ON THE SUNNYSIDE MURAL

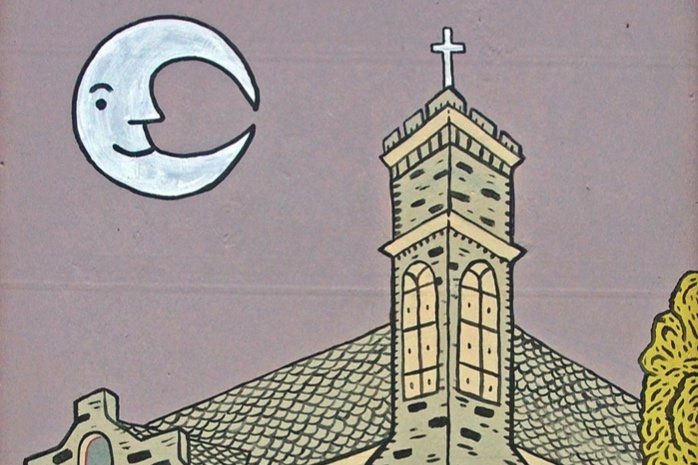

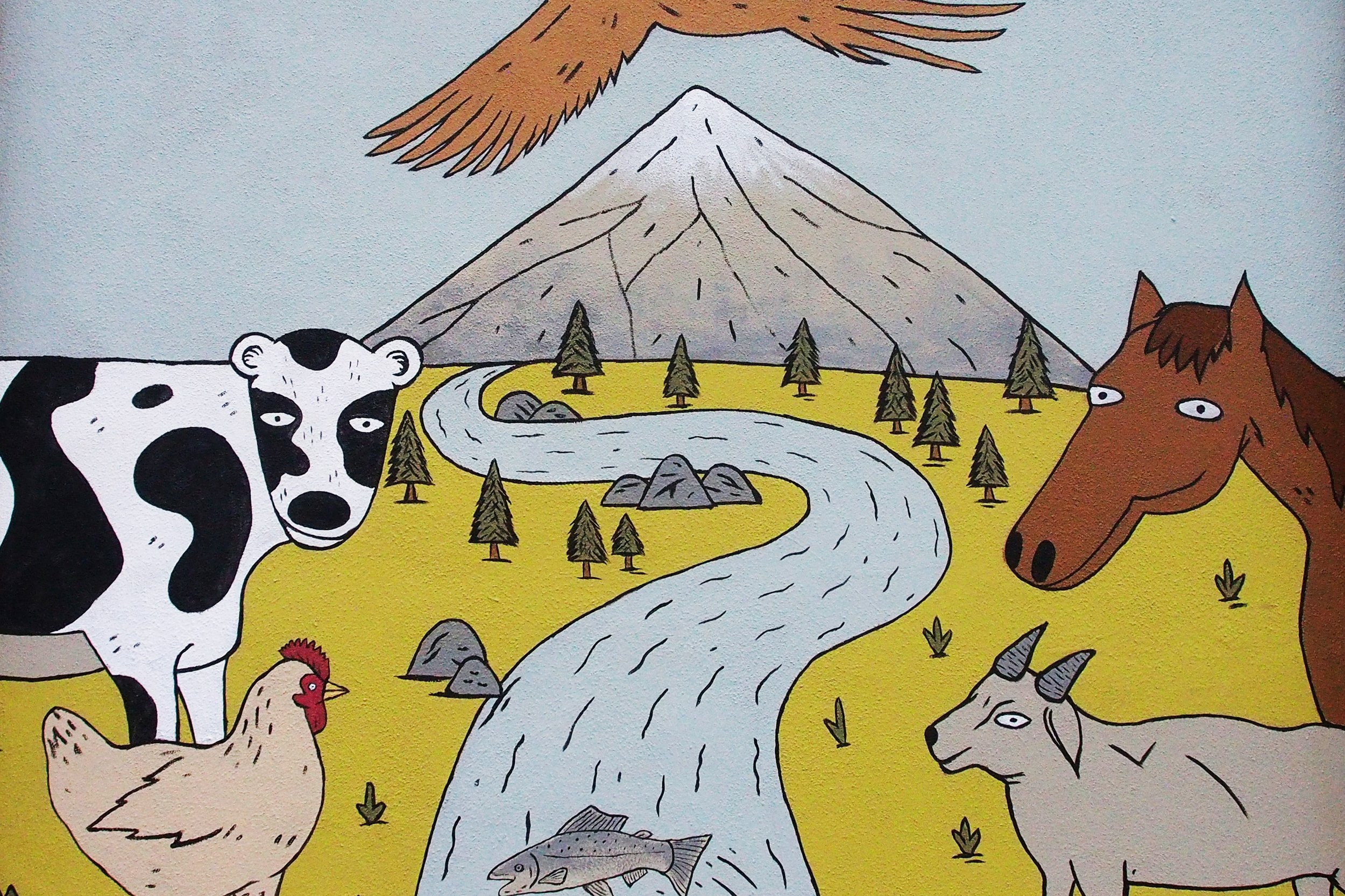

With extensive research and community outreach, PSAA worked with local street artist Maddo Hues (@yomaddo) to design this 100-foot mural that represents significant elements of the Sunnyside neighborhood's past and present. The project was sponsored by @seuplift and community donations. PSAA donated all of our management time, along with countless volunteers from the community who helped us prep the wall, deliver flyers and send emails. We hope that this mural serves as a platform for exploring Sunnyside's rich and vibrant history and a daily reminder that no matter how grey it might be, to always try to keep on the sunny side of life!

THE PLACES + THINGS OF SUNNYSIDE

EARLY SE PORTLAND HISTORY

The Portland metro area rests on traditional village sites of the Multnomah, Kathlamet,Clackamas, Chinook, Tualatin Kalapuya, Molalla and many other Native American tribes.They created communities and summer encampments along the Columbia and Willamette Rivers and harvested and used the plentiful natural resources of the area for thousands of years. The first white settler in the area, in the late 1820s, was a French Canadian fur trapper named Etienne Lucier. At the time Lucier arrived in East Portland, it was "heavily timbered with a thick undergrowth of laurel and fern." He built a cabin just south of where Hawthorne St is now. The cabin was later occupied by an employee of the Hudson's Bay Company, which was held in trust by John McLoughlin. In 1845, McLoughlin sold the land to James & Elizabeth Stephens. Mr. Stephens was a cooper and ferryman by trade. The original cabin is gone, but the Stephen's house still stands at the corner of SE 12th & Stephens St, and is the oldest structure in SE Portland. Despite the marshy conditions down by the Willamette River, Stephens started ferrying pioneers across the river to downtown Portland around 1861.

In early years Sunnyside was full of farms and fur trappers.

During the first three decades (1860s-1880s), East Portland was mainly occupied by fur trapper cabins and small family farms.The area Sunnyside encompasses today was settled on a portion of the Seldon Murrary land claim. A United States Land Patent, signed by President Andrew Jackson on March 19, 1866, was issued to Seldon and Hiantha Murray. They farmed the land for six years, then started to sell it off in portions for $10 an acre. Sunnyside and Lone Fir Cementary are part of the original Murray land claim.

HISTORIC HOUSES

The Thaddeus Fisher House

In 1888, Thaddeus “Thad” F. Fisher and his wife Phoebe escaped the city and built a house just off Belmont at the edge of the city. Thad was a prominent Woodsmen of the World, a man of earnest endeavor who bore the respect of all who knew him (Multnomah County Archives). The house was built in the high style of Queen Anne, popular during the late 1800s. They planted plum and apple trees which still stand to this day. Highly ornamental in design, the house included intricate woodwork, intersecting cross gables, a 3-story tower, and a steeply pitched irregular roof. A large veranda coils around half the main house. Set back and slightly higher than the street, the ‘life’ of the house is thrust upward into the sky, establishing a sense of continuity between the house and the surrounding overgrown setting. On almost a daily basis, people take pause on the sidewalk looking at the house, pointing, talking, and sometimes asking questions. Old neighborhood residents often stop by to reminisce and tell tales of the house’s past.

The Fishers were a well-off couple. Thad was a sea merchant during a time when Portland was becoming a key hub for shipping in the west. This house would have surely been a bold statement, a symbol of their class standing. During this time, the production of new inhabitable space on Portland’s Eastside was just beginning. Flight from the discords wrought by the industrial machine age was an achievement mostly possible for those who were wealthy enough to move. The elite were on a quest to escape the grimy city and reconnect to the natural world, enjoy sunlight, fresh air, greenery, and open space. SE Portland would have been a very different type of place to live in the late 1800s. The majority of the roads were still dirt and gravel, which turned to mud during the rainy months (Portland Paving Map). Horses and kerosene lamps were everyday objects, as electricity and automobiles were bourgeoning ideas. The Fishers, and their neighbors, were urban pioneers settling in and taming this new environment. There would have been an enthusiasm brewing in the Sunnyside neighborhood, because the very same year the Fishers built their home, the Mt. Tabor streetcar line began, extending from the river to 34th and Belmont.

The Fishers did not have any children. Thad passed away in 1904 and was buried down the avenue at Lone Fir Cemetery. His wake was held at his home. A few years after Thad passed away Pheobe remarried a man that was boarding in the house for many years, Edgar Allen. The house remained in the Fisher family until 1935 when Phoebe sold it. Interestingly, Edgar is buried right next to Thaddeus in Lone Fir Cemetery, along with his son, but Phoebe lies in an unmarked grave in-between her two husbands.

In the 1930s the home was temporarily converted to eight units during World War II (National Register). Portland’s mushrooming defense industries led to a housing crisis. This epic migration consisted of factory workers, soldiers and their families. Measures were taken to build worker housing, but the demand could not be met, so thousands of single-family houses were converted to accommodate multiple families. Even though the Fisher house is large, it would have been tight quarters. Residents would have shared bathrooms and kitchens. Many would have most likely viewed this home as temporary as they hoped the war would be.

After the war, the house was converted back to accommodate a single-family and the in the 1960s, it was rehabilitated and turned into three apartments by local preservation legends, Jerry Bosco and Ben Milligan (founders of the Architectural Heritage Center). In the early 1970s, when I-405 was under construction, they were alarmed by the tragic demolition of historic buildings throughout the region and salvaged countless architectural pieces. Over several decades, they collected a trove of ornate building elements, some of which were used in the restoration of the Fisher House and the neighboring J.C. Havely House. Dedicated to saving pieces of Portland history, Ben and Jerry worked extraordinarily hard restoring the original siding, repairing and replacing the shingle work, windows, doors, and woodwork.

On the left, Fisher House, on the right Buttertoes

J.C. HAVELY HOUSE

The charming Buttertoes Restaurant was open for a decade in the J.C. Havely House at 3244 SE Belmont. It opened in December of 1979 and closed in 1989. Owned and operated by three sisters who grew up in Portland – Carolyn, Charmon, and Cherous. Their grandmother was an early SE Portland pioneer who, in the early 1900s, lived in a house near a creek at 14th & Salmon in the Brooklyn neighborhood. This early pioneer house is still owned by the family. It was brought on horse-drawn trailer and moved to its resting place at SE 26th and Lincoln. Their grandmother worked downtown, as a bookkeeper for Singer sewing machines. She would take the trolley to 21st & Powell (the end of the line) and walk home from there. Their great uncle owned a sewing machine store on Powell Blvd for over 50 years.

The three sisters always loved cooking. When they opened Buttertoes, Carolyn, the oldest, had just finished her physiology degree at college at Warner Pacific College, and was looking for something to do. On a rainy Independence Day, the sisters were sitting around a fire, and started talking about running a restaurant. And that was that, they started a business!

When they started looking for a location for their new restaurant venture, their friend Jerry Bosco offered them the bottom floor of the Havely House on Belmont. The Havely House was built in 1893 by J.C. Havely, a railroad tycoon. Caroyln was told by a customer that the house once hosted SE Portland suffragette meetings in the late 1880s/early 1900s.

Buttertoes Restaurant famous Mermaid Painting, by David Delamare.

Perhaps the most lasting tale from Buttertoes was those spurred by the Ghost of Aunt Lydia. A friendly ghost, with a high-collared dress, black shoes, and her hair pinned up. Lydia would move things in the kitchen around and rearrange the table settings. The cook and manager once saw a woman go into the back room (which had no exit) and when they went back there to see who it was, no one there. One of the waitresses finally quit because they felt so uncomfortable, and Carolyn and the sisters didn’t like going there by themselves. The tenets who lived upstairs in the rental apartment also reported strange things, like rocking chairs moving without anyone in them, and strange dreams. A psychic finally came into the restaurant and did a reading, and confirmed a spirit was present. These stories live on today in the Pied Cow, as it seems that Lydia still haunts the old house.

EXPLORE THE MURAL

MAIN STREET

EARLY LAND USE

HISTORIC BUILDINGS

PIECES OF SUNNYSIDE

SHARING IN SUNNYSIDE

COMMUNITY GARDEN

SACRED SPACES

BELMONT FIRE STATION

THE PEOPLE OF SUNNYSIDE

Just a few people who built and shaped Sunnyside neighborhood

The first panel shows the many people of Sunnyside. From L to R John McLoughlin of the Hudson Bay Co, Jenny Joyce the original Belmont mural painter, Bertha Greene owner of Conrad Greene Grocery, Georgia the Yellow Lab, Sculptor Jim Gion, The Avalon Theater Clown, Mike Clark, founder of Movie Madness, the Alien and Girl with Headphone from the original Belmont Mural, Bill “Sharpie Bandit” who helped paint the original Belmont Mural, A man and his dog from the original mural, Founder of the Horse Brass Pub, Don Yonger, Jimmy Chen, owner of the Pied Cow Diner, and Bloodgood family baker.

The second panel features former residents Ben + Jenny riding next to the trolly through Sunnyside.

PEOPLE AND PETS OF SUNNYSIDE

BEN + JERRY

JERRY BOSCO +

BEN MILLIGAN

Ben and Jerry saved some of Sunnyside’s most iconic buildings, painstakingly restoring Victorian-era homes in Sunnyside. With their massive collection of architectural pieces, Ben & Jerry founded the Bosco-Milligan Foundation Architectural Heritage Center in Portland

CAROLYN NEWSOM

Co-owner of whimsical Buttertoes Restaurant, which dished out legendary Portland food for over a decade (1979-1989) out of the HavelyHouse on Belmont. Read all about this fairy-tale like production, the hauntings of the house, and her lifelong friendship with neighbors Ben & Jerry.

DAVID DELAMARE

Artist and illustrator David Delamare lived at 41st and Hawthorne for many decades. An avid theatergoer and musician, his mystical illustrations had a signature and otherworldly style. He painted the fabled mermaid that hung in the dining room of Buttertoes. David, and his work, was widely beloved.

LEARN MORE

YAE Camp 2018 Re-Cap

2018 YAE Camp Re-Cap

In August 2018, Portland Street Art Alliance and WolfBird Dance hosted the first annual one-week summer camp for female-identifying youth ages 11-14. YAE! Young Artists Empowerment Camp was held at Clay Creative in the Central Eastside Industrial District of Portland. This program provides youth a platform to develop their artistic voices and find empowerment through art and dance.

During the two-week camp, ten youth from diverse communities across Portland were provided street art and street dance training, accompanied by workshops to learn about the pillars of hip hop and the history and background of this culture: Graffiti (freedom of expression in public space), MC-ing (rhythmic poetry, aka rapping), DJ-ing (artfully blending melodies using a turntable), Breakdancing (a highly expressive style of street dancing), and Knowledge (skills and community building). We dove deep into the fundamentals of hip-hop dance, focusing on free-styling techniques, battling tactics, and how to learn and remember choreographed patterns. They also received lessons in letter-making, drawing, aerosol painting techniques, mural composition, and paint safety.

YAE! Camp provides young women a platform to feel empowered and become creative, productive, and confident members of our community. YAE! Camp offered instruction from an eclectic staff of dancers and artists to display diversity in all forms of artistic professionalism. We brought guest speakers throughout the week to talk about their art and other programs happening in Portland, also lead by women. With the culmination of this camp, students worked together to create a choreographed dance, participate in an all female dance battle, and collaborate on the development of four different murals (one of which is still on display to the public at 420 SE Clay St in Portland). Our students presented these performances and murals at our final YAE! Camp wrap party, closing out the program with an opportunity for our young artists to show off their new skills to friends, family, and the community.

Draw

Daily black book sketch sessions help get creative energies flowing

Talk

Daily guest speakers helping to teach, inspire, and build community

Mix

Break out sessions with local DJs to learn the basics of turntable mixing

In the mornings, camp participants were guided by mentors from WolfBird Dance to explore how freestyle and hip-hop can provide empowerment, healing, and comfort in one’s own body. With the support of five main dance camp mentors, we taught the fundamentals of different styles of hip hop such as Krump, Wacking, and popping. We also provided the tools and understanding of how to develop your own freestyle voice and what techniques to use in a battle, while simultaneously teaching the importance of how to learn and retain hip hop technique and choreography. On the final day of YAE! Camp, our ten campers performed their choreography and participated in a final all-female dance battle.

Style

Learn the fundamentals of hip hop freestyle dance

Jams

Coming together to develop new moves, encouraging each other to let loose

2018 YAE Camp | Dance Re-Cap

The afternoon session was led by members of the Portland Street Art Alliance. Campers were guided through the entire process of creating a mural, including visualizing, sketching, and painting with aerosol and brush basic techniques. They were provided both one-on-one and group lessons with PSAA’s mentors. The final collaborative YAE! Camp Mural is on-display in the garage of Clay Creative, now a part of the larger Taylor Electric Project, a historic site in the Central Eastside of Portland that provides rotating wall space for local artists.

Practice

Daily aerosol spray painting lessons from established local artists

Collab

Learning to work together as a team to create something bigger

2018 YAE Camp | Art Re-Cap

Guest Artists + Speakers

Throughout YAE! Camp, we brought many local guest speakers to spend time with the students and share their art forms and life experiences. This provided an opportunity for the girls to communicate and interact with artists they look up to in a non lecture/authoritative setting. It was important for us to ensure that the girls felt like a part of our community and that they could speak to their role models in ways that would encourage seeing themselves in these artistic roles. This year, our guest speakers included:

• DeAngelo Raines (Art Not Crime), who spoke about the history of graffiti and hip hop culture.

• Local female street artists, Wokeface (@wokeface), All the Veg (@alltheveg), and Flowering Jane (@flowering_jane), who showed the girls their work and the wide range of styles that street art can embody.

• Local female DJ, Kaeli Hertz, who taught about mixing and turntable techniques as well as her experience in the industry.

• Ella Marra-Ketalaar, a Community Engagement Coordinator at the Regional Arts & Culture Council.

• Jesus Rodales (Find A Way), a local Portland dancer and activist encouraging cultural understanding of hip hop dance, who taught about the origins and history of street dance.

• Daisy Lim, a dancer from New Zealand, who taught the fundamentals of Krump and how to use creativity and imagination to be a storyteller with movement.

• Katie Janovec (The Aspire Project), a Portland based dancer who spoke about the fundamentals of popping.

• Bao Pham (ADAPT), another Portland based dancer who demonstrated the possibilities of movement by combining many styles of hip hop, creating her own unique movement vocabulary.

On the final day of YAE! Camp, we encouraged a “show and share,” an opportunity for the girls to share something unique about them, and a time for us as mentors, to encourage the girls to use this individuality in their art. Many students shared from their black books (YAE! Camp provided sketch books, for the girls to keep and practice in) their drawing styles.

One student from Mongolia shared her new found passion for taking graffiti style lettering and transposing it onto Mongolian letters. Two other students taught us about traditional African and Mexican dance. They brought the oufits required for these dance styles and performed some of the dances for us. One student told us she now likes experimenting with incorporating traditional African dance moves into her freestyle practices.

Camp was extended by two hours to invite friends, family, and the community to come see what we created and learned together. Students performed a choreographed dance, showing off their new moves and training on how to collaborate, move through space and remember choreography. Their participation in an all-female dance battle, showed their knowledge of artistic choice in free-styling and freedom of expression through dance. We then presented their group murals. The teams presented why they chose their design, what it meant to them, and their favorite camp experiences. This event was not only an opportunity for our students to show their work, but also a chance for the community to see what we can be build when a safe space for learning and creativity is provided to young emerging artists.

Feedback + Testimonials

The response and support of YAE! Camp from our students, parents, and community was unbelievably humbling. During the wrap party, students also had the opportunity to provide camp organizers feedback on the week's activities. A short anonymous survey was distributed to the youth. Eight of the nine girls ‘strongly agreed’ that they liked YAE Camp and would want to attend again, with one girl saying they ‘agreed’ and would 'maybe' come back.

2018 SPONSORS + DONORS

One of YAE! Camp’s main goals will always be providing affordable access to quality arts training. In its first year, we awarded seven 100% scholarships, one 75% scholarship, and one 50% scholarship. YAE Camp 2018 was partially funded by a seed grant from the Open Meadows Foundation. In addition to sponsoring 3 schalorship spots, Killian Pacific provided the use of vacant space in Clay Creative for the camp. Ike's Tug & Supply (@kobrapaint_ikestugandsupply) donated all of the spray paint.

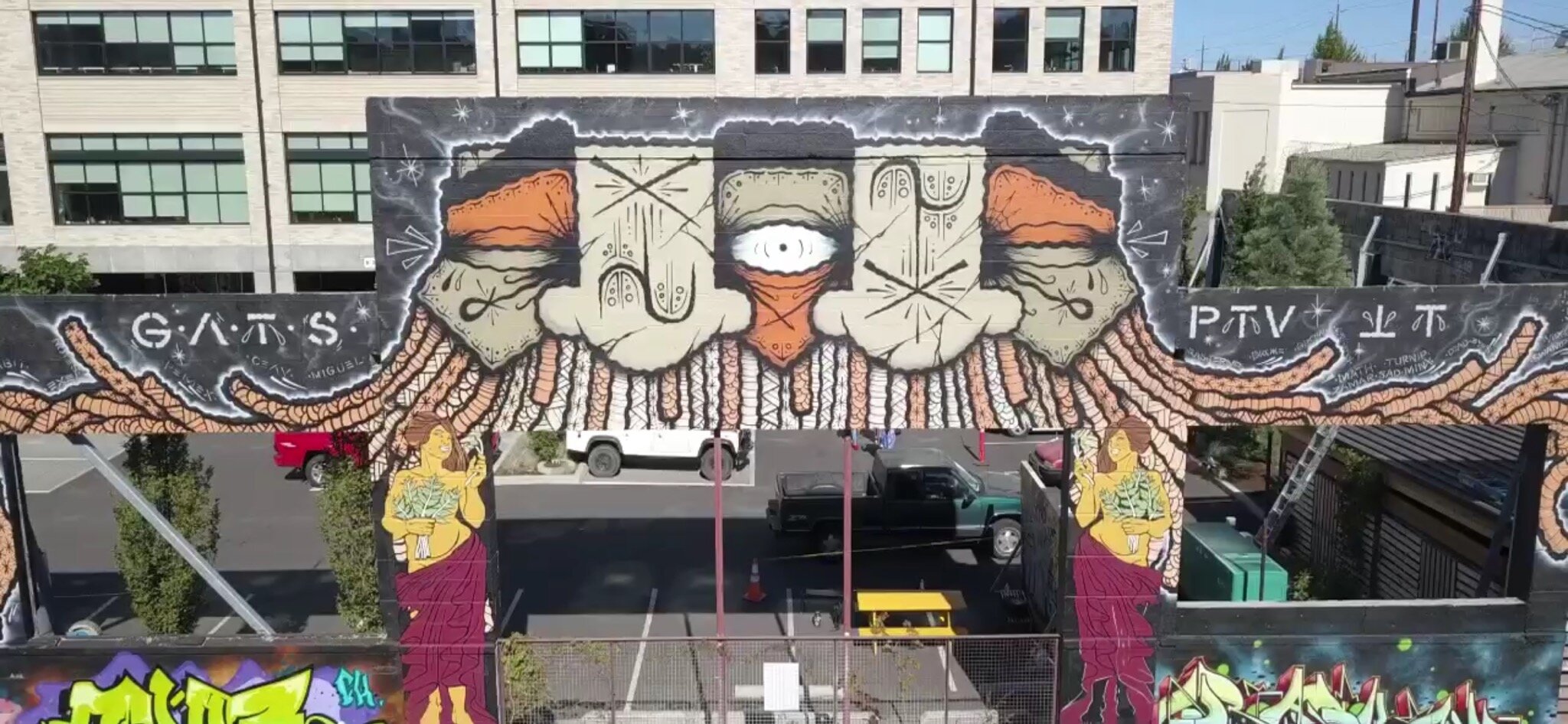

GATS + N.O. Bonzo Mural

We would like to share a bit of history about the two muralists, GATS and N.O. Bonzo and their work. Seeing the artwork is striking, but it is also important to know and understand the motivations and personal stories behind the imagery.

For 13 years, GATS, an artist from California, has brought their iconic mask imagery to blank walls all around the world. The mask, which is often likened to an octopus, represents a global identity that breaks down all barriers and prejudice. Inspired at a young age by the punk rock and skateboarding scenes, their iconic image has developed over time, and can be seen in cities and countries across the world from Jerusalem to the Philippines.

Pilsen Walls, Chicago IL

GATS focuses on painting artwork for struggling communities, such as the houseless and at-risk youth, many of whom don’t have access fine art and can’t visit galleries or museums. Last year, GATS recently painted a mural inside Janus Youth’s offices in downtown Portland. Since 1972, Janus Youth Programs has provided a second chance for at-risk youth with few resources, and no place to turn for help. In an interview with Street Roots, GATS explained:

“When you’re houseless, you don’t own a wall, let alone art to hang on it. Most people in that situation don’t browse Instagram for entertainment or feel socially comfortable hanging out in galleries. A mural to someone in this situation will have infinitely more meaning than someone purchasing a painting to decorate their house. I paint houseless shelters to give the building soul. Oftentimes they feel institutional. Your environment has a huge effect on your psyche. If your room looks like a jail, you’re going to act like you’re in jail. If your room feels like a home, you’re going to take pride in it. Also, when you’re low, you don’t want to be bombarded with over-positivity that comes off as insincere. I just wanted to make the place look cool without it feeling preachy. The last thing you want is to feel like you’re being judged when you ask for help. Seeing something familiar when you walk into a space makes you feel like you’re in the right place.” [Street Roots, 4/20/17]

Janus Youth, Portland OR

GATS is also well-known in the contemporary art world, as galleries are eager to show their work. GATS has had sold-out solo shows in Hashimoto Contemporary (San Francisco), Spoke Art (Spoke Art), Takashi Murakami's Hidari Zingaro Gallery (Tokyo), and many more. They have a significant fanbase and following on social media, with even legendary street art documentarians Martha Cooper and Herny Chalfant being followers and amongst their gallery show audiences. Every time a new GATS artwork goes up in a city, a flurry of art lovers and photographers scurry to go see and document the work. The character is a true symbol of universal humanity and grassroots resistance that tens of thousands of people around the world identify with.

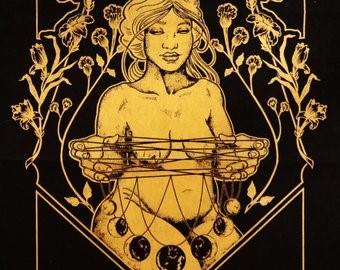

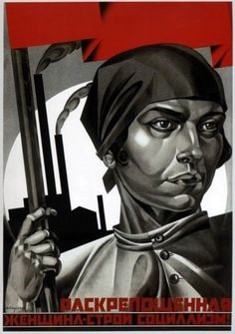

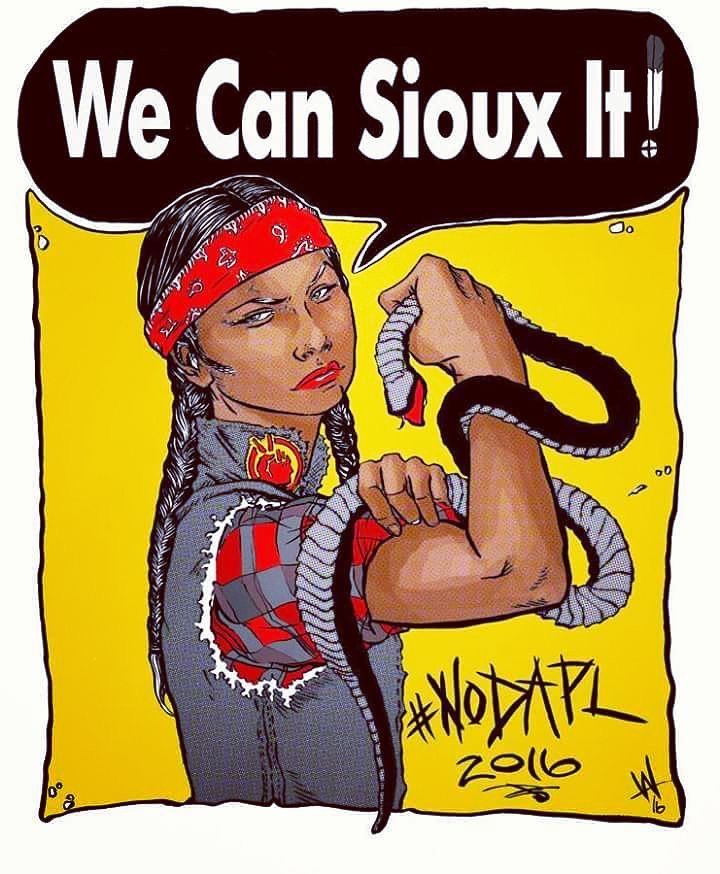

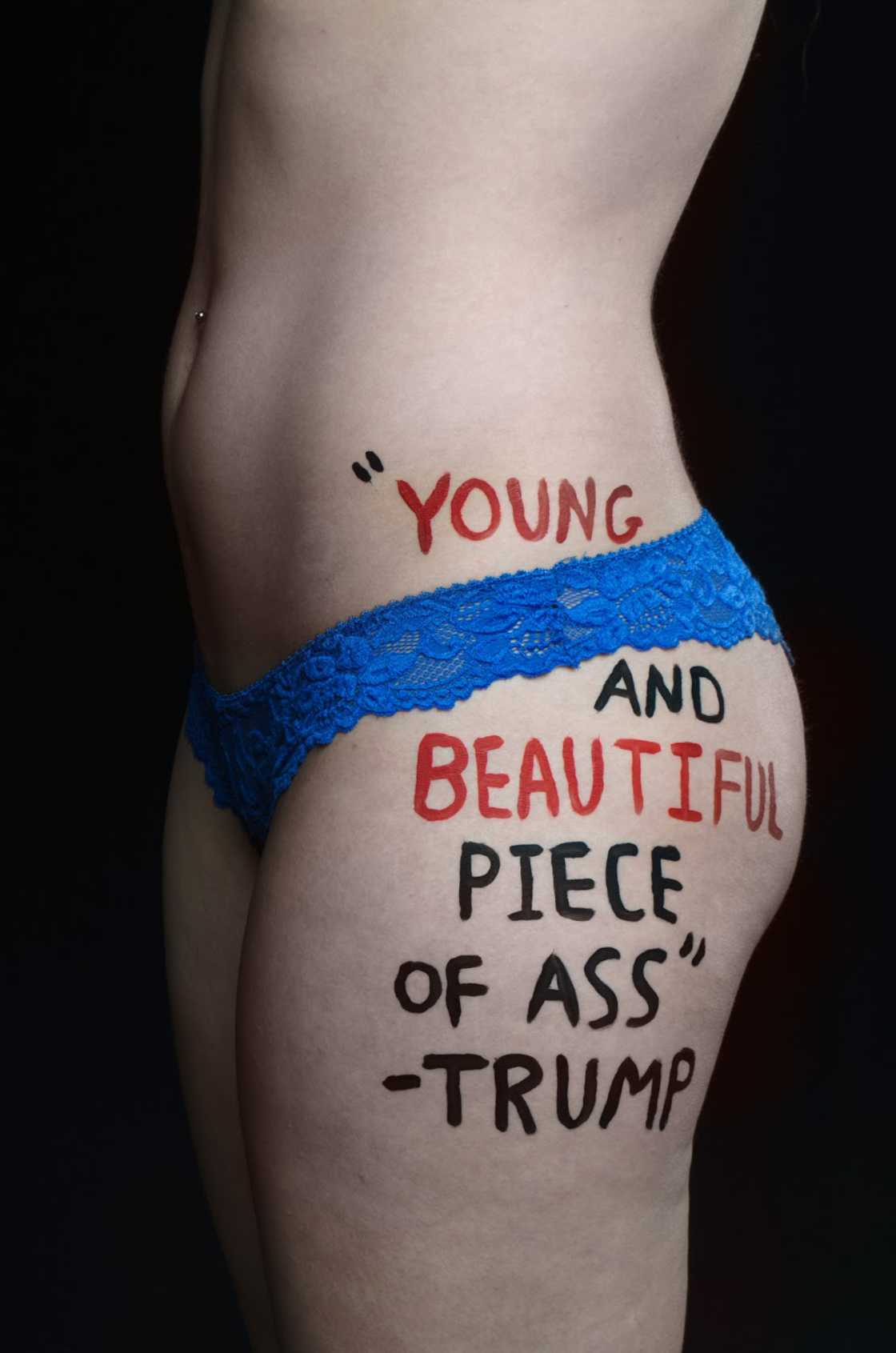

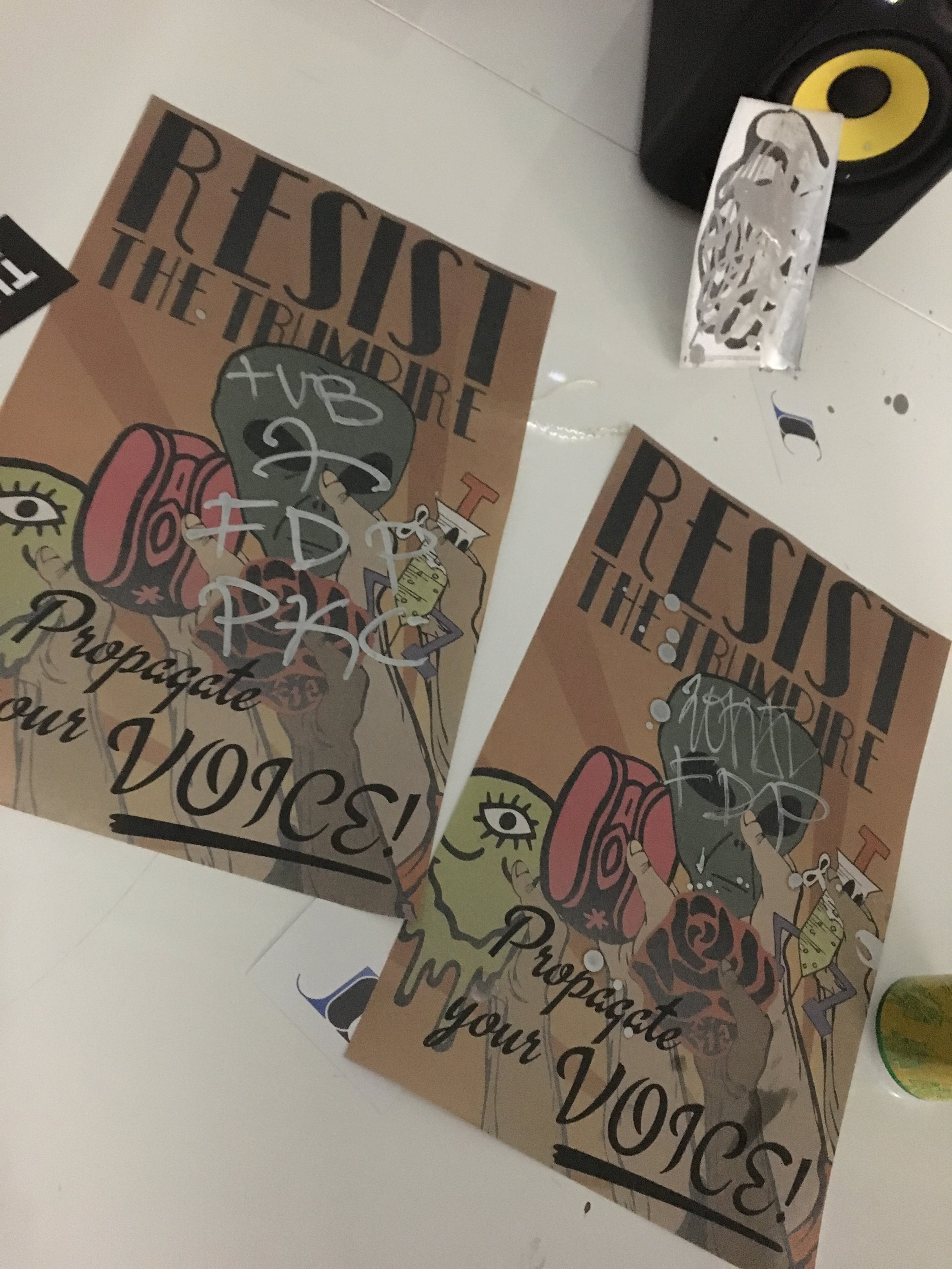

Local Portland artist N.O. Bonzo has been painting with GATS for over a decade, here in Portland and in cities across the Pacific Northwest. N.O. Bonzo is a notable and highly respected artist and printmaker in her own right. Her work focuses on anti-fascist imagery, women's resistance, environmentalism, sex worker rights, and police/prison abolition. N.O. Bonzo’s strikingly beautiful style often focuses on powerful female imagery often adorn with local and medicinal plants. She is known for her meticulous attention to detail, mixing her own homemade vegan inks, inlaying gold leaf, and even painting with rust. In 2014, she hosted a gallery art show at Portland’s Upper Playground called “Drowntown” raising awareness of Portland’s epidemic of depression and suicide. The red string held by the women in the Oregon Theater mural, are a nod to weaver and spinners guilds.

N.O.Bonzo and Circleface Mural | Dekum Community Garden Portland, OR

In a recent local interview, she described her personal experiences and the motivations behind her artwork:

“I think a lot of us who are drawn to doing this work, do so because we in some way have these overwhelming personal experiences and dominant cultural narratives telling us we don’t matter and no one values us. I came from a lot of trauma and domestic violence, and pretty early on saw the state’s unwillingness to intervene in that violence, and the communities’ (at that time) inability or lack of concern around disrupting it. A lot of the organizing and work I do nowadays surrounds community intervention and support around domestic and sexual violence. Most of my pieces are highly personal in ways that for me are easiest to communicate visually. I draw the people I do because you don’t often see women portrayed in anything other than highly consumable and passive objects. The only place you’re ever going to find folks who are telling their own stories in city space, is with the traditional and modern mural artists, graff writers, and street artists. I want to see folks who experience marginalization getting up and taking space in completely unapologetic and challenging ways in whatever feels best for them. For me the space that I’m drawn to challenge those dominant narratives, is on city property.” [It's Going Down, 8/16/16]

Portland Street Art Alliance is honored to work with these two immensely talented and passionate artists, and we are thankful to the Oregon Theater for allowing this artwork to be shown on their walls and providing us a canvas to create new public art in the City of Portland.

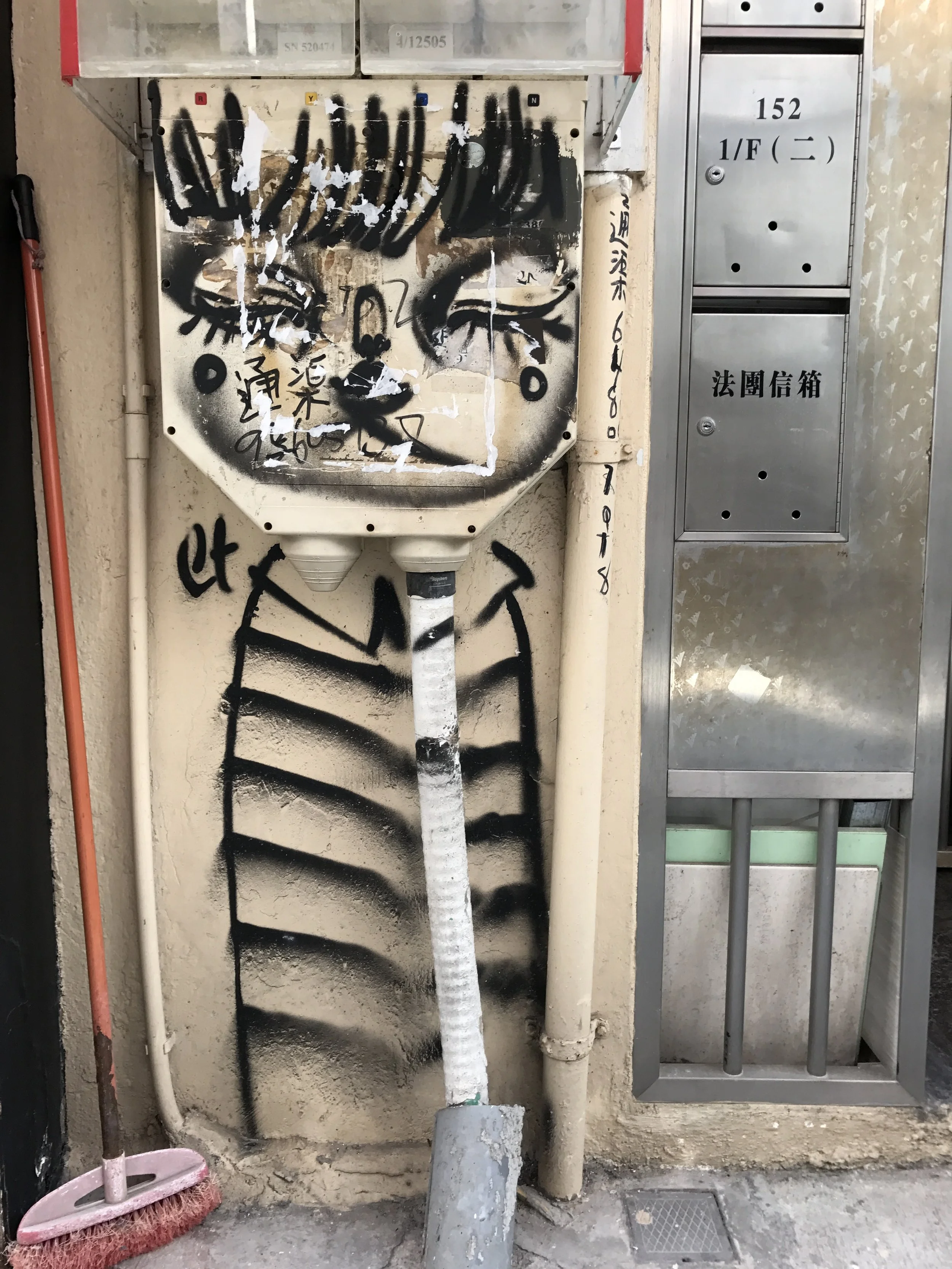

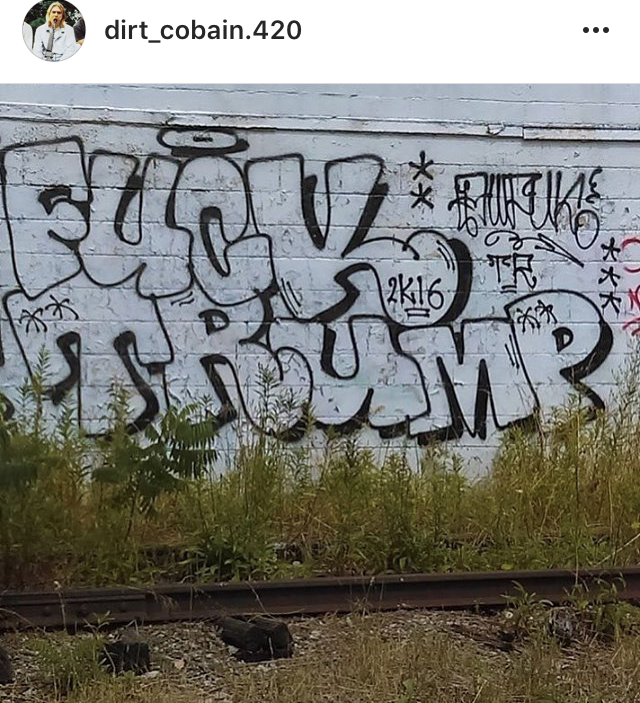

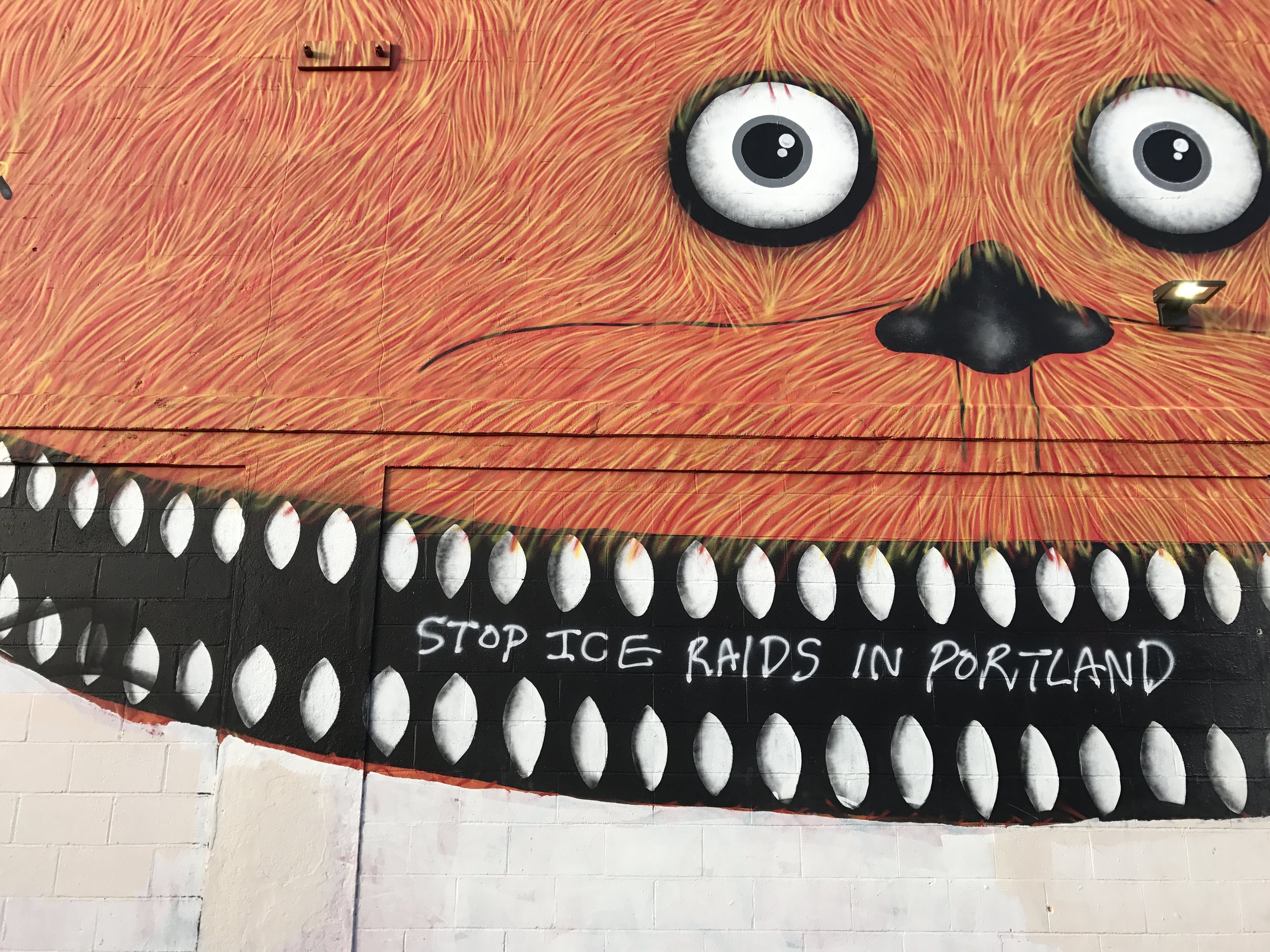

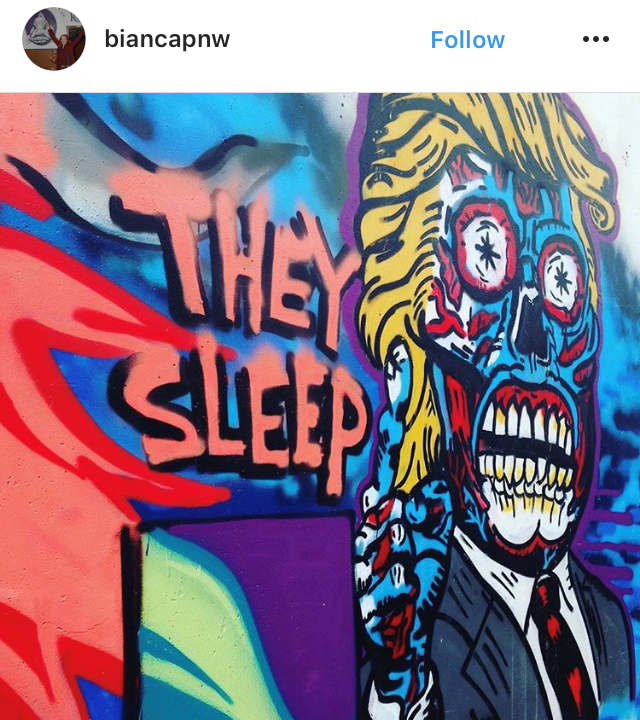

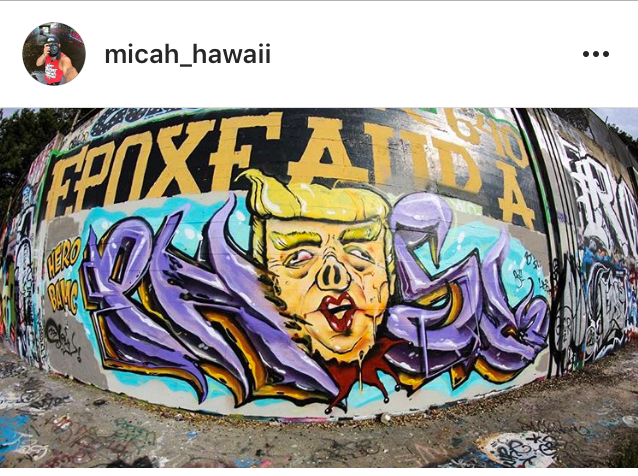

Rotating Graffiti Art Walls

A brief overview of several rotating graffiti art walls in the U.S.

Tacoma Graffiti Garages | Tacoma, Washington [2008-2013]

The City of Tacoma partnered with a private property owner to transform an open-air parking garage in downtown into a free space for graffiti. Paint was only permitted on Sundays only. This program was done in partnership with the City of Tacoma and its impact was tracked by the city. The city aimed to: 1) connect with artists who would not necessarily apply for a permit or grant and 2) provide a safe space for people to paint in public. In their research, the city found that graffiti in the immediate vicinity increased slightly, but the overall amount of graffiti found in the city reduced. The free wall in essence concentrated graffiti into a centralized space. The graffiti garages became a community gathering space, tourist attraction, and populate film and video shoot location. A few complaints were received early on, but pushback eventually subsided. Eventually in late 2013, the garage owner chose to stop allowing graffiti at the site citing safety and overuse as the cause for their decision.

Community Chalkboard | Charlottesville, Virginia [2007-Present]

The Community Chalkboard + Podium is an interactive, democratic, and uncensored monument to the first amendment, offering the public a venue to practice of the right to free expression. The chalkboard is 60’ by 7’ high, and made of slate. It is located directly in front of Charlottesville City Hall and is part of an area known as First Amendment Plaza. Due to the low barrier medium, a wide array of people interact with this wall on a daily basis. This project joins educators, artists, and designers with local youth to explore and interpret the places where they live. It acts as a public discussion board for a variety of discourse including political, social and global issues. It has received an Urban Excellence Silver Medal in the Bruner Award Program. The Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression manages the wall, and the design came from Architects Peter O'Shea Wilson and Robert Winstead. Cleaning and maintenance is done mostly by volunteers who live or work nearby, and it is cleaned at least twice a week since it is so popular.

Free Expression Tunnel | Raleigh, North Carolina [1968-Present]

A long pedestrian tunnel under the railroad tracks at North Carolina State University has served as a public free wall since 1968, when it was first painted to celebrate returning veterans. Anyone is permitted to decorate the tunnel walls at any time. Campus clubs and organizations often paint the tunnel to promote events and graffiti artists use it as practice space. Since 2010 there has been an ongoing tradition of a weekly ‘freestyle cypher’ where local artists and students gather to freestyle, beat box, sign, play instruments, recite poetry and network. The tunnel has only had one documented issue come up, which occurred after President Obama was elected. Racist graffiti appeared with threats against Obama. The U.S. Secret Service quickly identified the four students responsible for the hate graffiti and the students were expelled.

Post Alley in Pike Place | Seattle, Washington [1993-Present]

Since 1907, this labyrinthine of angled streets and steep grades in downtown Seattle has maintained a distinctive physical and cultural character. One of the main points of interest of Pike Place, for both locals and visitors alike is Post Alley. This alley gets its name from the Seattle Post, which used to be located at the alley's southern end. Today, the narrow alley passage is famous for its gum and wheatpaste art wall. The gum tradition began in 1993 by patrons of a nearby theatre. It is unclear how long the wheatpaste art wall has existed, but it's past is likely intertwined with the historic tradition of pasted city notices and advertisements, especially considering this is a high-traffic corridor once occupied by a newsprint company. With both the gum and wheatpaste walls, the Pike Place Market management and the City of Seattle police take a “hands off” approach to these public interventions, allowing and even somewhat encouraging freedom of speech and expression in these spaces. Both have become a huge tourist-draw, attracting visitors to participate in this public intervention and snap photos. Over the years, the gum has spread quite a bit. So much so that local street artists have attempted to clean the gum off the wheatpaste side of the alley. The City of Seattle's sanitary department finally stepped in to help clean off some of the build-up in 2015. City crews undertook a multi-day process to completely clean the alley. Within hours of being clean the gum started to re-appear and artists from all over the Pacific Northwest descended upon the alley to reclaim one side of the alley for pasted paper art. For the foreseeable future, Post Alley is one of the United States most open and accessible spaces for public art and expression. No permits or scheduling is needed, just show up anytime of the day or night with a pack of gum or wheat paste and go to work

TUBS | Seattle, Washington [2007-2014]

For 7 years, the former 104-year old building known as TUBS sat vacant at the corner of 50th and Roosevelt in the University District, amidst a bustling urban neighborhood. In 2009, the building owner thought it's demise was near, so they invited graffiti artists to use the 12,000-square-foot space as a canvas for their art and expression in the meantime. The owner wanting to provide the community an "ephemeral and evolving" piece of curated street art. Over time, the space opened up even more to other artists, and it essentially became a free wall - a hot spot for Seattle graffiti. A year after the free wall began, the City had received over 900 graffiti complaints. But the building owner fought back, citing their private property rights and community appreciation for the art. By this point, TUBS had become a tourist destination and like many graffiti meccas, served as an urban backdrop for photographers and filmmakers. In response to the complaints, the City of Seattle said they're hands were tied and they had no power to force the owner to clean up their building. Seattle City Attorney Ed McKenna said, "Legally, we're in a difficult position. We can't force the owner to remove his graffiti, so we have pretty much have exhausted every remedy." The City of Seattle defines graffiti as "unauthorized markings." The difference with TUBS was that the building owner willingly allowed their building to become a "free wall," so the City of Seattle could not fine or penalize them for graffiti. The free wall at TUBS continued for 6 more years until 2014 when it was finally demolished to make way for a large condo building. The TUBS free wall was an important piece of Seattle's urban art history and unique when it comes to other cities in the U.S.

SODO Freewall | Seattle, Washington [2012-2013]

The owners of a warehouse building on Occidental Avenue across from the Starbucks Headquarters, in the SODO neighborhood of Seattle welcomed graffiti artists of all types to come create art on an over 100-foot wall that backs up to the train tracks. This was a non-formally managed project where artists have free reign, and the work changed often. Because the project was on private property and backs to an industrial area, there was minimal conflict with the larger community over the activity and content surrounding the project.

Olympia Free Wall | Olympia, Washington [2000-Present]

This free wall is located on the backside of the State Theater, in downtown Olympia. It is part of a network of urban alleyways. The walls near the free wall are marked with warning signs to not paint here and are buffed regularly to control spill-over graffiti.

HOPE Outdoor Gallery | Austin, Texas [2011-Present]

This ‘community paint park’ is located in downtown Austin, TX. This educational project is managed by the non-profit HOPE Events and was launched in 2011 with the help of street artist Shepard Fairey. The paint park provides artists, arts education classes, and community groups the opportunity to display large-scale art pieces driven by inspirational, positive and educational messaging. The park has broadened based on the response from local families, community members and the Austin Creative Class. It has become an inspirational outlet and creative destination for all that come to visit and is recognized as one of the Top 10 Artistic destinations in Texas. The park has provided many benefits to the community including job creation for local artists, connections to art commissions, a site for school classes and field trips, live art projects, dance videos, breakdancing and urban agriculture classes. The HOPE Outdoor Gallery is located on private property. Anyone over 18 years old who wants to paint must register beforehand by emailing the coordinators. An adult must accompany any youth wishing to paint or visit. When registering, artists are asked to fill out a question form, provide proof of ID, submit a sketch or mock-up of the art intended, and sign a waiver in order to receive credentials. The park is only open for painting between 9am and 7pm daily, and no one is allowed to paint after dark. Painting passes are available for pick-up on Saturdays and Sundays during designated hours. Painters without proper credentials (a painting pass) are asked to leave and may be subject to arrest for trespassing. All participants must respect the existing art, be courteous to the neighborhood and dispose of all your trash. In January of 2018 it was announced that the HOPE Outdoor Gallery is relocating and expanding with the creation of a new six-acre project launching at Carson Creek Ranch in southeast Austin.

5Pointz | Long Island City, Queens, New York City [1993-2014]

Starting in 1993, developer Jerry Wolkoff gave permission to a group of graffiti artists to decorate his building to try and deter vandalism in the area. Over time, the building became covered in vibrant street art and the building was rented to artists as studio space. The space was managed as a rotating art wall and artists needed to arrange to paint ahead of time. It was a mecca for artists from all over the world to come and add to the murals. For over 20 years, the location was a tourist destination, and also helped Long Island City become the vibrant neighborhood it is now. The owner eventually tore down the building, and the site is now the subject of a federal court case filed by the artists who say the artwork itself was their property based on the Visual Artists Rights Act. (V.A.R.A). The photos below were taken in 2014 after the notorious buffing of 5Pointz by owner Jerry Wolkoff.

Special thanks to PSAA Intern Erika Galt for help researching and editing this article.

Graffiti Abatement, Broken Windows and Zero Tolerance.

GRAFFITI ABATEMENT, BROKEN WINDOWS, AND ZERO TOLERANCE.

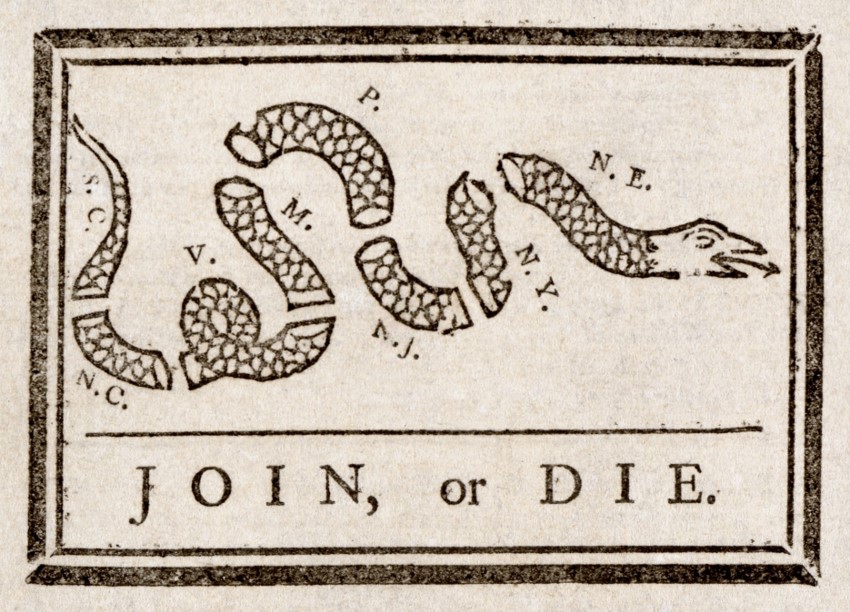

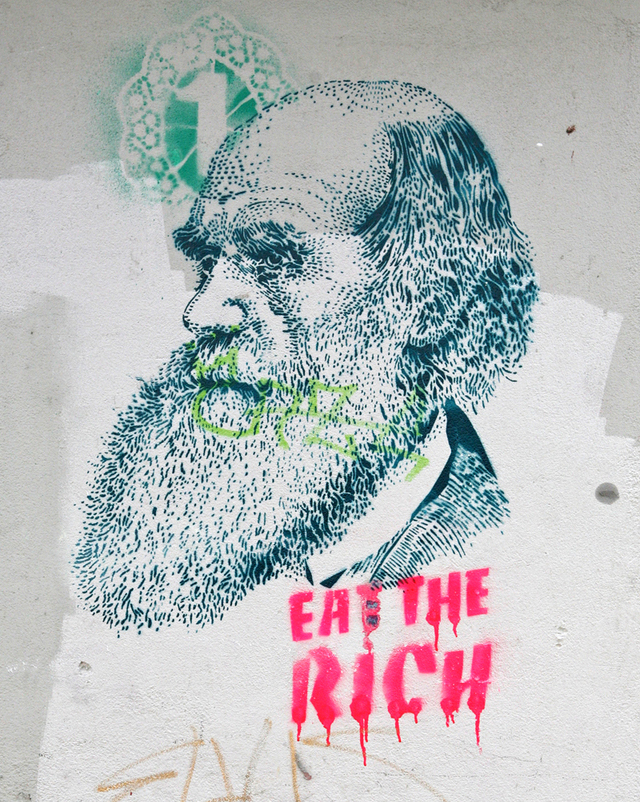

Graffiti is a polarizing phenomenon. For decades, its presence has fueled intense debate. For some, graffiti evokes fear and is viewed as strictly criminal vandalism; a destructive attack upon an otherwise clean and orderly society. For others, graffiti is seen as a natural form of human expression, a sign of a vibrant modern culture, and an important form of grassroots resistance. By definition, public space is supposed to be open to everyone. The quality of our public spaces, and the degree of access we have to them, speaks volumes about what we, as a society, believe to be important. Access to public space is important because these spaces serve as the only real arena for common democratic actions.

Across various municipal entities, the City of Portland spends an average of $2-5 million a year on graffiti abatement and removal. The City of Portland’s Graffiti Program began in 2007, operating under the Office of Neighborhood Involvement (ONI) now called the Office of Community & Civic Life. The City’s Graffiti Program employs one full-time program coordinator and a part-time assistant (as of 2017), who manage the program and organize volunteers to carry out periodic graffiti removal “sweeps” of Portland. The City allocates approximately $40,000 a year in community grants for graffiti abatement and prevention ($42,000 in 2010, $40,000 in 2011). Like many cities, it has codes regulating the sale of “graffiti materials,” such as spray paint and markers. It also has a Graffiti Nuisance Property Code that requires all reported graffiti to be removed within 10 days, or the property owner faces fines of $100 a day for everyday the graffiti remains. The City essentially operates under a zero tolerance policy where any graffiti reported (that does not have a city-issues mural permit or waiver) is required to be removed. Many of these reports come in through the City's Graffiti Hotline and the PDXReporter smartphone app. As of 2017, the Graffiti Program works in partnership with the Graffiti Task Force that meets monthly and consists of two dedicated full-time police officers who investigate graffiti crimes, public agencies and district attorneys. Although they have publicly stated (at the 2013 and 2014 Graffiti Abatement Summit) that the main focus of the graffiti police officers is to investigate gang graffiti crimes in East Portland and other urban outskirts, many in the community say that the officers focus more effort on easier and more visible targets, such as street art and graffiti in inner Portland and in the downtown core. The officers have come under public scrutiny for targeting street art collectives and owner-permitted works. Another key player in Portland’s graffiti abatement scene is the newly created Friendly Streets, a non-profit entity that promotes livability and works in partnership with residents, businesses, public and private agencies, local officials, utility companies and others, to foster safe, attractive, and well maintained city streets. Marcia Dennis, the former head of the City’s Graffiti Program, is the vice president of Friendly Streets and one of the board members is the owner of a for-profit graffiti removal company in Portland called Graffiti Removal Services.

Portland taxpayers spend between $2 to 5 million annually on graffiti abatement.

In 2012, Portland spent $3 million on graffiti.

Cities across the U.S. spend between $12 to 25 billion on graffiti abatement every year.

Many cities now outsource graffiti abatement. For-profit private graffiti clean-up companies are increasingly common.

Most graffiti occurs on soon to be demolished vacant buildings. Even these structures are continuously painted over (i.e., buffed).

Research shows that continuously removing graffiti does not eradicate it in the long term.

In tough financial times, are these expenditures justifiable? Can our tax money be better spent?

Portland’s graffiti abatement program supports building felony cases whenever possible.

In 2012, more than 100 people were arrested in Portland for graffiti.

Are felony charges really the best approach to prosecuting those caught doing graffiti? Do felony charges really deter graffiti or prevent repeat offenses?

Portland has a ‘zero-tolerance’ graffiti policy requiring that all un-permitted public expression be promptly removed.

If issued a citation, Portland property owners are required to remove graffiti within 10 days or face search warrants, fines, and possible imprisonment.

These policies are relatively new, and are based on the "Broken Windows" theory. Even though it did not directly reference graffiti when developed in the 70s, this theory is used by law enforcement to suggest that graffiti actually causes urban decay, the collapse of moral values, and physical violence.

If anything, graffiti arose as a response to, or a by-product of, urban disinvestment and desperate situations.

Research, including studies done by Harvard Law Professor, Bernard Harcourt, show that the broken windows theory has not been proven or adequately tested.

Should we blindly accept the broken windows theory? Is it right to stereotype people who do graffiti or street art as being violent criminals who lack moral values? Listen to this 2016 NPR segment about how this theory of crime and policing was born, and how it went totally wrong.

Anti-graffiti campaigns often criminalize artists and further the divide between them and the larger community.

It’s a common belief among anti-graffiti activists that graffiti is a ‘gateway crime’ that leads to other more serious offensives.

It’s estimated that less than 15% of all graffiti in the City of Portland is gang related.

Artists who do graffiti/street art come from all demographics. It is a world-wide phenomenon.

Why can’t we work to educate the public about the different forms of graffiti (and how to identify gang graffiti) so there’s less fear and more understanding of this global subculture?

Portland no longer has any designated outlets for graffiti art – they have been systematically eliminated over the past 50 years.

Countless NW cities (Seattle, Tacoma, Olympia, San Francisco, etc.) have free/legal walls that are open to public expression. Free walls provide a designated safe place for people to practice and refine their skills.

School art funding has been systematically reduced over the years, providing less opportunities for youth to express themselves artistically.

Why not explore other options that provide youth the support and safety they need to develop artistic skills and the ability to interact with public space in a more acceptable way? Why not ask residents what kind of graffiti management they prefer? Would community-specific place-based graffiti management be a more effective than a blanket zero-tolerance approach?

Above all, PSAA wants to promote more dialogue surrounding these important issues. The City of Portland, in many ways embraces the weird and quirky. Many of us choose to live in Portland because of its quality of life and vibrant cultural scene. We believe that allowing for more free expression in public space ensures that everyone has an equal opportunity to express themselves and be exposed to art in their daily lives. Having a vibrant arts scene is also a vital ingredient that helps the City of Portland attract creative professionals and artists who want to live in vibrant, accessible, dynamic, and safe city.

Read more about incidents artists have had with Portland's graffiti abatement in our article covering the forced buffing of an owner-authorized mural by a world-renounded artist.

The City of Portland' Graffiti Abatement Project periodically organizes volunteer group "sweeps" to remove graffiti on public property along Portland's main streets. On Saturday June 28th 2014, the City of Portland’s Graffiti Program implemented a large graffiti cleanup of SE Belmont Street, between 20th and 40th Avenues. According to GAP, Belmont had been “hit hard with graffiti over the last couple of months.” Approximately 20 to 30 volunteers participated in this city-sponsored event, which provided graffiti removal training and a free continental breakfast.

A group of anonymous street art advocates participated in this community event to get a ‘sneak peek’ into Portland’s graffiti abatement efforts. As Morton’s clean-up crew moved down the street, they documented and provided satirical commentary about the politics of graffiti and graffiti removal; even going as far as interviewing a few passersby for their opinions. The next day, PSAA was sent the video below, and interviewed Morton and the other volunteer art advocates who participated in the Belmont Graffiti Cleanup Event.

In a classic détournement style, these advocates lightheartedly and subversively participated in an event that they would not have normally participated in. They wanted to see what was going on, and learn more about graffiti abatement tactics. PSAA would like to thank all the community members who participated in this neighborhood event, whether they were wearing orange vests, or simply having a conversation about what was happening around them. Strong communities are made up of an active and engaged public, so regardless of our opposing opinions on the issue, we’re happy to see people outside trying to “improve” our shared public spaces.

After speaking with participants of the event, PSAA like to pose a few questions for the city to consider: first, why spend time and money funding events that focus on scraping stickers off the back of street signs? As long as the front of the sign stays clean (for obvious safety and informational reasons), why not meet us halfway – let the community put art on the back of our street signs. Seattle takes this moderate approach, why can’t Portland? These signs are, after all, public spaces. Second, why not focus more on removing (and fining) illegal profit-driven advertisements? Ads vandalize our public realm, often without penalty. The same is not true for community members who choose to speak through art on the streets.

PSAA would like to encourage Portland artists and advocates to engage with not just their peers, but reach across the aisle and talk to the City and your neighbors. Try to understand their perspective and tell them about your perspective too. Even though we have differing opinions about how to best maintain and manage our shared public spaces, we should try to find commonalities and work together in whatever shared spaces we can.

PSAA's Full Interview with the Street Art Advocates:

PSAA: Why did you guys participate in the Belmont Graffiti Cleanup Event?

Morton and Friends: We wanted to help our community, make it a better place. We love our city and we want to change the world we live in. We wanted to remove blatant and illegal advertisements, in addition to stickers that were old, worn, and tattered. We saw this as cleaning the canvas, making way for fresh DIY art stickers. We also wanted to see what graffiti abatement was up to and how they managed events like this.

PSAA: Why do you think the City of Portland sponsored this event?

Morton and Friends: At the event, the main reason the City said graffiti removal was important to do was to make sure that tourists were not scared away from visiting certain Portland neighborhoods. As far as the focus on Belmont, who knows… they said it had been “hit hard,” but really Belmont doesn’t have any more graffiti than any other popular Portland drag.

PSAA: What were you and the other volunteers asked to do?

Morton and Friends: We were told to focus on removing stickers and a bunch of anti-abatement protest signs that had been put up along the cleanup route. When we questioned the organizers about why they were not removing ALL the other flyers on the poles, they told us to not worry about those and just focus on the anti-abatement signs. We thought that was weird because as flyers are illegal postings too. Otherwise, volunteers were told to focus on removing stickers from poles and the backsides of street signs.

PSAA: So they said to only remove stickers from the back of signs, what about the front of signs?

Morton and Friends: If the front of a sign had stickers on it, we think the entire sign was replaced in a lot of cases. I guess the solvent can damage the reflective coating on the signs, so they just have to remove and replace the whole thing. The cleaners they gave us did a good job removing the stickers pretty quickly, the stickers mostly slide right off. If the sticker didn’t come right off, they said to just scratch and destroy the sticker enough to make it unreadable.

PSAA: What did you take away from participating in the Belmont Graffiti Cleanup Event?

Morton and Friends: Surprisingly, we came away with a new understanding for the similarities between graffitists and graffiti abaters. Both want to make an impact on our community and make a positive difference. Both act to change the aesthetics of their environments. Both feel like it helps their sense of community. The main differences (between these two communities) are that aesthetically, one likes seeing community interventions and art, and the other, likes a blank, and in our opinion, very sterile environment. Also, one group uses the streets as a space to exert their right to free speech. The other group sees it as their duty to suppress this speech in the name of the law. We all felt like we were making a difference in the world!

All Photos © PSAA

Let Dreams Soar, but Not on Your Private Property

The “Let Dreams Soar” mural is located in St Johns neighborhood of Portland. This privately commissioned piece of art was recently given a stern warning by the City of Portland. The mural, created by longtime local artist, Adam Brock Ciresi was created over the span of 4 days, and depicts crows and children soaring through the sky with DIY wooden wings, under the iconic St. Johns Bridge.

Shortly before the mural was completed, the homeowner who commissioned the piece received a notice from the City of Portland. A neighbor made a complaint to the City, simply stating “Adding murals to the house without permits. Children jumping off St. John Bridge.”

Even though there are plenty of grey areas in the City’s complicated mural code, and the fact that there are plenty of un-permitted murals around on residential properties, the City was forced to respond to the complaint and take action.

Per the City’s current laws, murals are prohibited on private residential buildings with fewer than five dwelling units. Therefore, the “Let Dreams Soar” mural was not able to be permitted since it is on a single-family house. The City ordered the owner to buff it immediately or face massive daily fines.

Ciresi tried everything he could to secure a permit before staring the mural. However, like many other artists and property owners in Portland, they thought they would just take their chances and paint. Right now, the City is technically forced to consider this mural as an illegal “sign.”

A petition to save the mural was started by local supporter. As of Sept 11th 2017, the petition gathered an astounding 6,619 signatures. Even City Commissioner Chloe Eudaly signed it – the person it was to be delivered to, as the head of the Office of Neighborhood Involvement (ONI) and BDS, the bureau of the City that oversees and issues mural permits.

Commissioner Eudaly has thankfully now stepped in more directly, putting a pause on BDS giving any citations or fines. The City hopes to figure out a way of amending the law, and make it possible to process residential murals within the current code. Working with Commissioner Eudaly and the Regional Arts & Culture Council (RACC), Ciresi continues to push efforts forward to find a resolution and make this change in law happen.

“It’s sort of an archaic law that we are up against,” says Ciresi. With the support of the homeowner who commissioned the mural, Ted Occhialino, and a large number of St. Johns and Portland-area residents, Ciresi is gearing up to fight this in court. “If that means we’re becoming an advocate for loosening these laws around public art and where they can and can’t be placed, then so be it. I’m ready,” said Ciresi to the news.

The City of Portland is long overdue to re-evaluate its mural laws which were created back during the early 2000s after a long legal battle following a law suit by Clear Channel. Many things have changed since then, and the phenomenon of urban street art has since exploded across the world. Portland needs to accommodate for this new and ever-evolving landscape of creativity and intervention. Along with the residential building restriction, PSAA has also asked the City to modernize and automate its mural application process, and re-evaluate the 5-year rule to allow for curated, rotating art spaces in the city.

On August 26, 2017, Ciresi was invited to participate remotely in the Veterans of Peace Conference in Chicago, a national non-profit organization dedicated to the abolishment of war. Within the forum, Dan Shea, Veteran and Mural Coalition participant, talked about the mural controversy and the importance of mural art and activism. In the interview with Ciresi, they discussed the mural’s legal issues and the uplifting motivations behind it. “Art is something that confronts people and has a different perspective to look at and they can imagine how it would be, the meaning of it, not just the skill, but the meaning of it all,” Shea states, referring to murals and artists like Ciresi. Shea is an artist as well, and also brings up his struggle with advertising companies when it comes to painting murals in public space. Veterans of Peace identifies strongly with the situation because they see the value of landmarks. Murals show a glimpse of history that belongs to the city and support the fact that murals, just like “Let Dreams Soar,” serve the community and become landmarks for younger generations.

This situation is unfortunately not unique - censorship of street art has happened in other cities around the U.S. It sometimes only takes one complaint to put a piece of public art at risk of being buffed.

A now famous case surrounding two murals created for Living Walls in Atlanta Georgia were removed due to a few residents finding the works disturbing, offensive, and pornographic. Living Walls is an annual gathering of international street artists aimed at uplifting the community in a city with the nation’s highest number of foreclosures. One of the murals was painted by Argentine artist, Hyuro, and depicted a nude woman with a timid non-sexual demeanor.

Three months later, Pierre Roti, a French artist painted a self-funded mural of an alligator only to have it buffed a few days later. The image of an alligator-head man with a serpentine tail that was suppose to be an allegory about the brutality of capitalism, not a statement on religion or demons, as it was perceived by some residents. “The best thing you could say about the alligator painting was that people didn’t understand it… It absolutely did not represent what people want to see on a busy street every day,” Douglas Dean, former state representative expressed.

The Department of Transportation then stated that it wasn’t an issue of artistic value, but instead it was a matter of proper permits. Living Walls works in accordance with the property owners and permits from three city departments. The City Council members say otherwise—public art ordinance requires approval of the full Council, which Living Walls did not receive, hence its removal. It was also added that the state’s public art policy prohibited works that “include any content that could possibly divide a community”—welcoming Living Walls to put up new installations as long as they meet requirements.

Monica Campana, founder of Living Walls, worried that the decision of the removal of both pieces would stir fear in artists who come each August from all over the world—“no one wants to paint a wall that is going to get painted over. We don’t think we have to paint a rainbow and butterflies to make art that represents a community.”

Another similar case unraveled in 2016, when a mural in Toronto Canada came under siege. Homeowners commissioned a local artist, Kestin Cornwall, to create a mural of Drake; the well-known rapper. Fay and Small had purchased the Croft Street house with the knowledge of it being on artistic strip, and supported community artistic expression. A few days after the piece was completed, they received a letter stating that the City had been made aware of their property being vandalized and is in violation of Toronto Municipal Code.

This story made it to local CBC Toronto News, who then contacted the City of Toronto and had them send out a spokesperson to inspect the mural. His final verdict; “It’s fine.” The City responded that when they receive a complaint, the letter automatically sends to the homeowner rather than sending out an officer each time. Fay had a different opinion on the matter; “The City shouldn’t be sending out blanket letters, sight unseen… For a city to just blindly shut down a piece of art on a street that’s deemed kind of an art-alleyway, that’s just bizarre.”