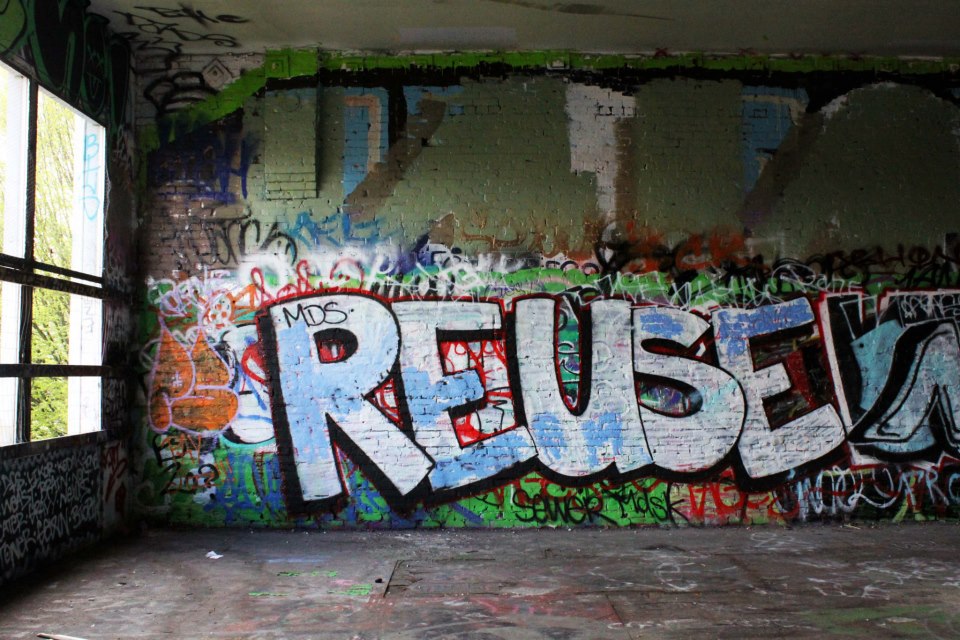

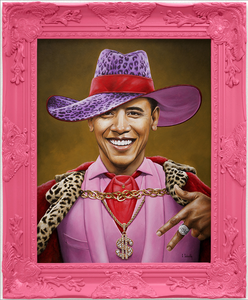

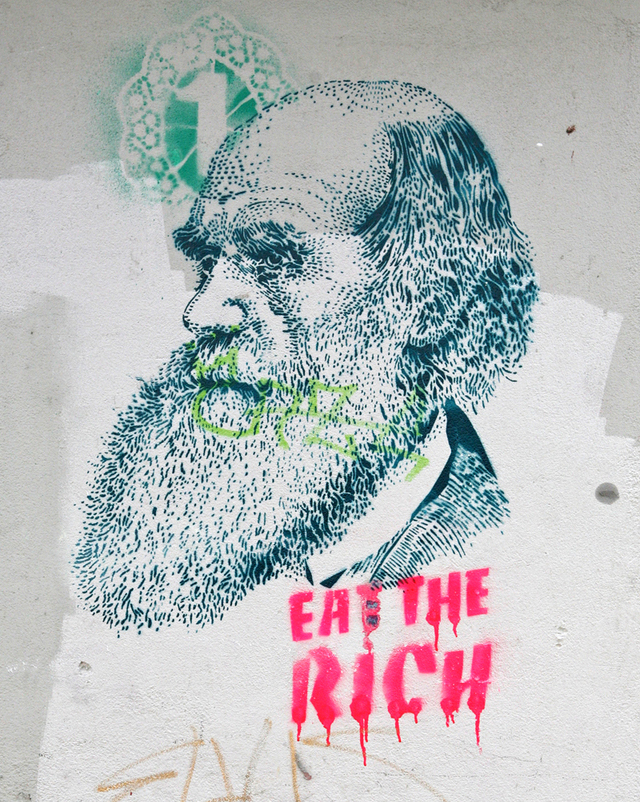

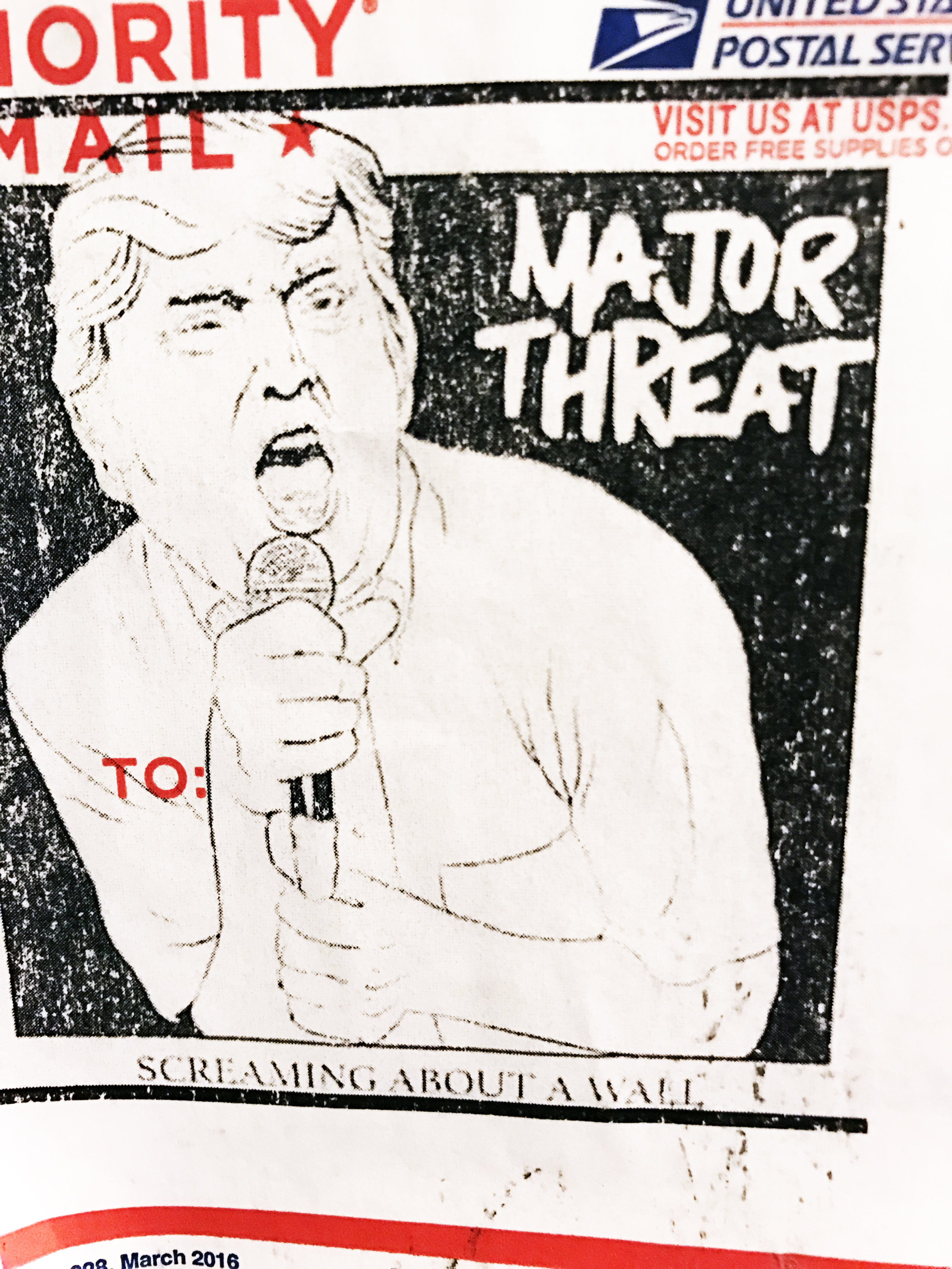

A painting on a wall is different only in size and accessibility to the public from those on canvas or paper. Real artists paint on buildings and cars and busses. The fundamental legal issues facing mural and street artists are relatively straightforward. Most of us are aware that painting on a building or other public property can lead to civil and criminal liability. Less often considered are the interesting and nuanced legal issues concerning copyright and ownership of the work itself. How the work got on the wall does not alter the legitimacy of the expression, the work can even be vandalism and also protected by copyright. Although communities vary in artistic preferences, especially in their regulation of public art, the expressive and aesthetic value of art is separate from its status in that regulatory process. The fact remains that even “street art” is real and as advocates for arts and artists it is something we should come to terms with. In fact many cities and businesses in America (NIKE, Vans, Levi’s, and Frito Lay) have embraced this work both to advocate the legitimacy of street art, and to utilize this young urban medium for commercial purposes. Street artist Shepard Fairey helped define the brand of the last presidential election, inviting hordes of young people into the political process. Shepard Fairey is an ambassador.

Especially relevant to the public artists are the rights regarding the attribution and integrity of the work, which is part of the 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act that became part of copyright law. VARA applies to the work of artists who paint on building walls. Important rights also control secondary uses of the art such as the making of copies, t-shirts, postcards, posters, and other commercial goods.

How Copyright law applies to Murals

Copyright law is grounded in our constitution to ensure a continuing incentive for creativity. Copyright protects “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” This means the author of an original work in a tangible medium of expression owns the copyright in that work from the moment of creation: the copyright springs into existence as soon as the pen leaves the paper (starting with the cartoon), or the paint hits the wall. The law applies to the work of Shepard Fairey, Jeff Koons, KAWS, Joe Cotter, Larry Kangas, and Robin Corbo the same as it applies to any other artist.

The rights of muralists under Copyright law

Once an image is “fixed in a tangible medium of expression,” the creator of the work enjoys the exclusive right to make and distribute copies, to display the work publicly, and to make derivative works (subsequent copyrightable creations based on the original work). Through stencils, sketches, and the final image, the muralist fixes this creative expression “in a tangible medium;” thus, earning the protections afforded by copyright law.

While the rights to the work itself pass to the owner of the wall by nature of the wall; ownership of the copyright stays with the author. Under copyright law, the artist is the sole holder of the copyright to his creations; however, if a piece is painted onto a building owned by another, the building owner is the rightful holder of that particular “copy” of the work. Lawyers can split this hair separating the copyright in the art from the rights in the work therefore; the building owner could cut out the wall on which the art was placed and sell or lend it.

A building owner cannot, however, begin making t-shirts, mugs or advertising with the design because doing so would constitute the creation of unlawful derivative works or copies--the building owner is no longer using the wall, but instead, is using the art itself. Similarly, a photographer could not legally photograph the wall and then proceed to sell or license the copies. Capturing the painting in photographs is a copy or derivative. It would be a derivative work to use the patterns in the artwork to make fabric designs, packaging, or as promotions for film or video projects. Most major film and video productions obtain clearances for murals appearing in background shots. The art is a valuable tool to establish the "look and feel" of a location.

The ownership of the rights can change if the artist gives the rights to someone by signing a “work for hire” agreement which has the effect to transfer the ownership of the rights in the work. That agreement must clearly state that the work will be considered a “work for hire.” There are good reasons why a street artist may not want to demand credit for his work nor trouble himself with copyright and compensation. If we are talking about graffiti, making such a demand could expose the artist to civil and criminal liability for vandalism, trespassing, and a host of other potential violations. These uncredited artists miss out on some copyright protections recognitions and royalties in their copyrights and devalue their otherwise legitimate work.

The artists can also give up the rights in the artwork with a license, transfer or assignment of the rights in the work. The artist can give up some or all of the rights, its up to the seller and buyer.

The Duration of Copyrights

For works created on or after January 1, 1978, when an artist creates a work under a pseudonym (for example, calling oneself “KAWS” instead of signing with one’s actual name) or creates a work anonymously, the copyrights in that work only lasts for the lesser of 95 years from first publication or 120 years from the year of its creation. However, if an artist’s identity is revealed in the registration records of the Copyright Office (including in any other registrations made prior to the expiration of the copyright term), then the term will last for either (a) the life of the author plus 70 years; or (b) in the case of a work made by more than one person, for the life of the last surviving author plus 70 years. These nuances often mean that an unattributed work fades into the public domain much sooner than an attributed work.

The Visual Artist’s Right of Attribution and Integrity

We know that a building owner can sell the building or the wall itself but cannot make t-shirts of the art. Another question is whether a building owner may paint over a given work of art. The standard provisions of copyright law only prevent people from violating the copyright holder’s exclusive rights which include distribution, making copies, and selling or licensing derivatives. The artist and copyright holder would typically be powerless to stop the destruction of the work except for VARA which might add additional rights. If the work is of “recognized stature” the artist may be able to prevent its destruction by exercising his moral rights under the Visual Artist’s Right of Attribution and Integrity (“VARA”).

VARA was enacted in 1990 as an amendment to the Copyright Act, to provide for the protection of the so-called “moral rights” of certain artists. “[M]oral rights afford protection for the author’s personal, non-economic interests in receiving attribution for her work, and in preserving the work in the form in which it was created, even after its sale or licensing.” VARA provides that the author of a “work of visual art,” “shall have the right,” for life,

(A) to prevent any intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of that work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation, and any intentional distortion, mutilation, or modification of that work is a violation of that right, and

(B) to prevent any destruction of a work of recognized stature, and any intentional or grossly negligent destruction of that work is a violation of that right.

How VARA applies to a mural including street art

Upon passing VARA in 1990, Congress instructed courts to use common sense and generally accepted standards of the artistic community in determining whether a particular work falls within the scope of the definition of a “work of visual art”, and explicitly stated that “whether a particular work falls within the definition should not depend on the medium or materials used.” Protection of a work under VARA can depend upon the work’s objective and evident purpose.

VARA protects only things defined as “work[s] of visual art.” There is no clear bright line standard for where this applies. The congressional debate “revealed a consensus that the bill’s scope should be limited to certain carefully defined types of works and artists, and that if claims arising in other contexts are to be considered, they must be considered separately” (Thus the “legislation covers only a very select group of artists”). VARA does not protect advertising, promotional, or utilitarian works, and does not protect “works for hire”, regardless of their artistic merit, their medium, or their value to the artist or the market.

As the quoted text reflects, VARA confers rights only on artists who have produced works of “recognized stature,” or whose “honor or reputation” is such that it would be prejudiced by the modification of a work. To determine whether a work is of “recognized stature,” courts typically apply a two-part test: (1) the work is viewed as meritorious and (2) this stature is recognized by art experts, other members of the artistic community, or some other cross-section of society. To satisfy this test, the artist will probably have to rely on expert witnesses; however, a long-existing work with some importance to the community should be sufficient. For the purposes of this determination, “recognized stature” can be either recognition of the work itself, or of the artist.

The rights of muralists under VARA

VARA grants artists a type of “moral rights.” For example, from the Büchel (Mass MoCA) case, part of the law provides that the author of a “visual work” has the right to prevent the use of his or her name as the author of the work of visual art in the event of a distortion, mutilation, or other modification of the work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation.

Under VARA, authors of qualifying works have the right to prevent its destruction. Destruction of such works can lead to substantial liability. In 2008, Kent Twitchell (an American muralist) settled a case under VARA and California’s Art Preservation Act (CAPA), in which he was awarded approximately $1,100,000 for the destruction (painting over) of his 70-foot-tall landmark mural of the iconic L.A. artist Ed Ruscha.

However, even if all the VARA elements are met, courts may still deny relief to artists who have illegally placed their works on property. This was the case when artists illegally placed artwork in a community owned garden on city property. When the interior construction by the artists was identified as a “work for hire” so the artists did not own the copyright (Carter v. Helmsley-Spear). It was also the case with a temporary mural (Pollara case) attached to a chain link fence in Albany New York, regardless of the artists reputation and quality of the work, political appropriateness, or value of the message. But it was not the case when the artist and museum disputed whether the work was “finished” and if it could to be publically shown (Büchel).

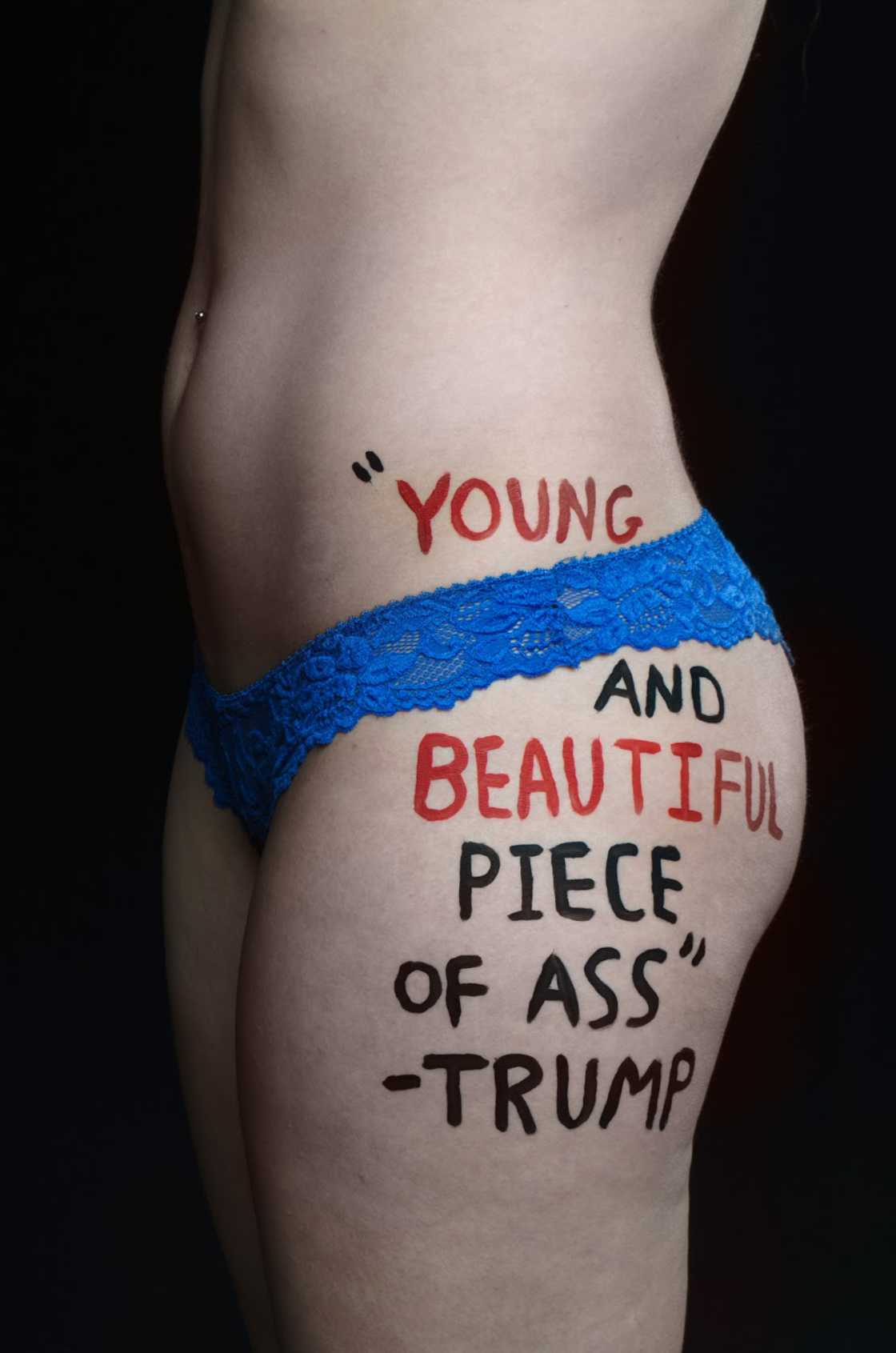

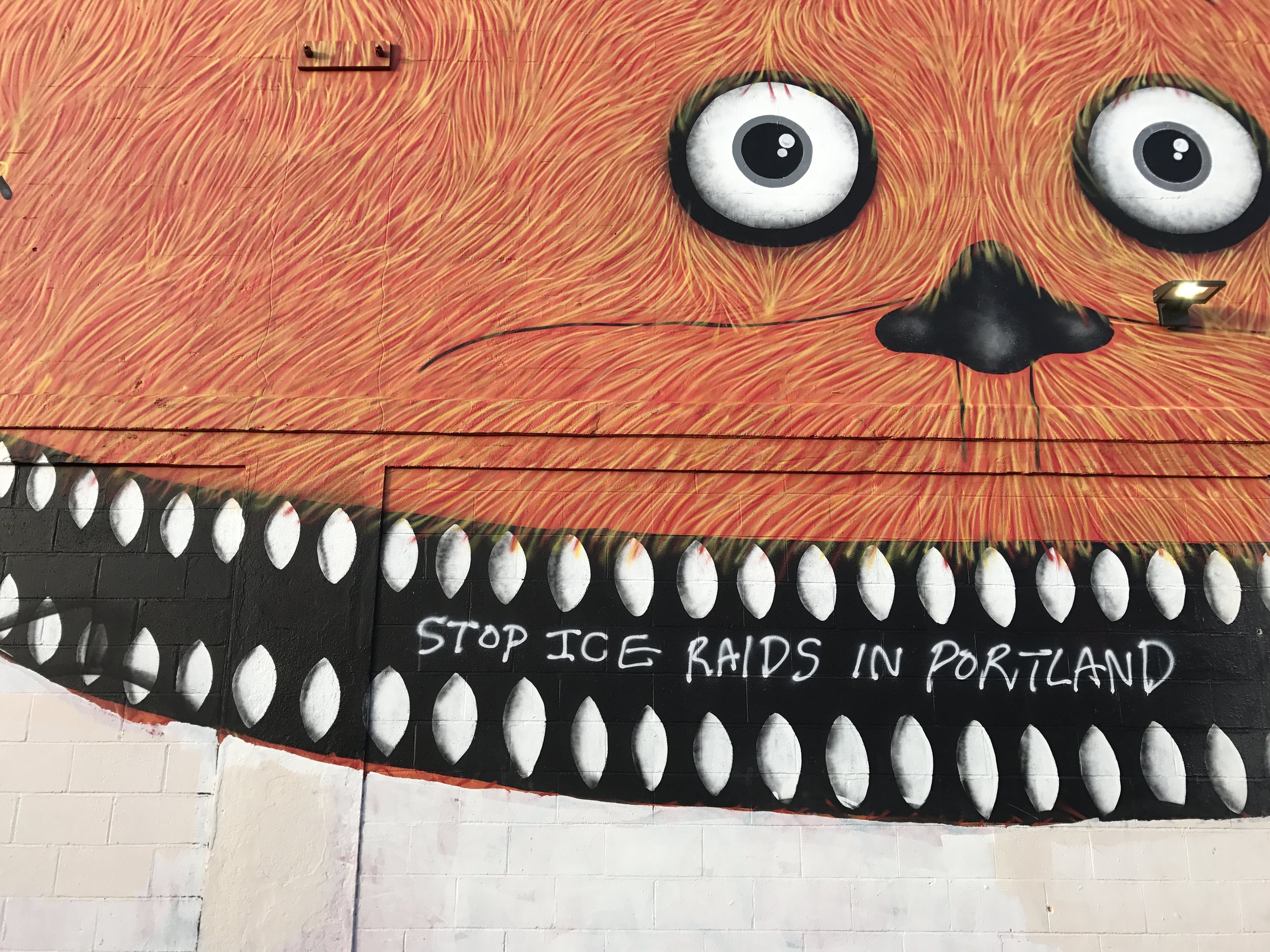

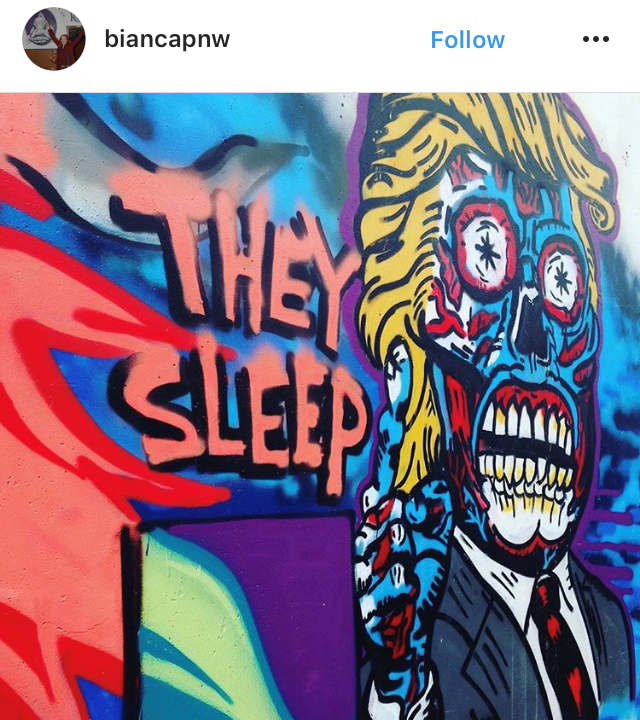

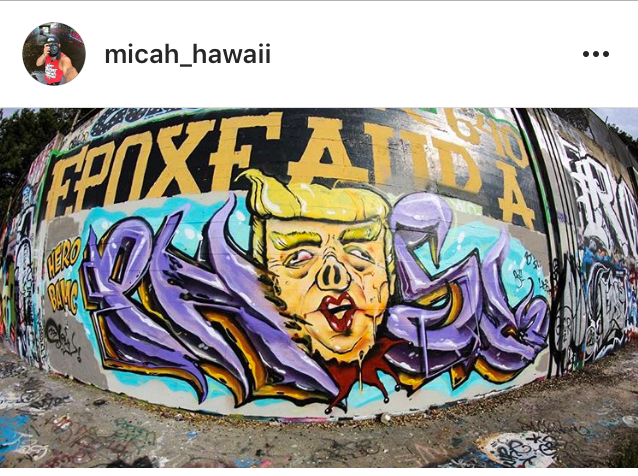

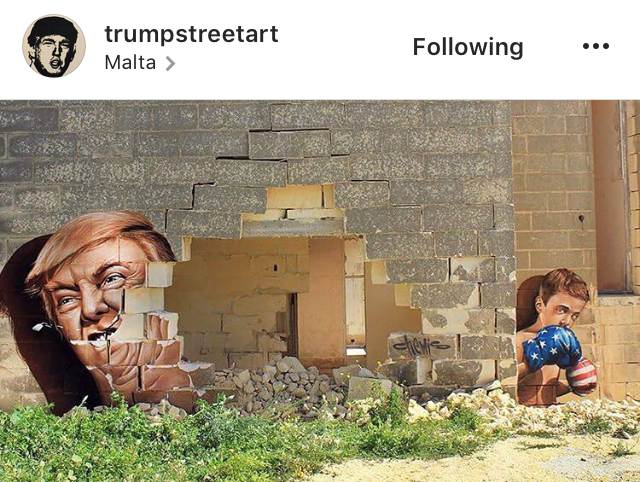

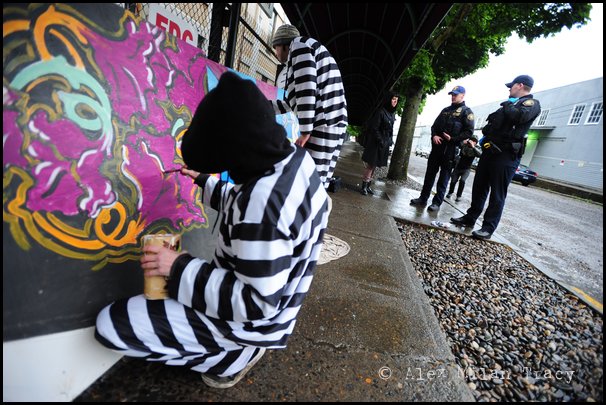

Unpermitted work in violation of the law

Under VARA, artists who illegally paint the property of another are probably without a means of stopping the destruction, removal, or transfer of that particular manifestation. As a result public pressure rather than copyright law is probably the best means of protecting such work—if the work is truly special, of recognized stature, or widely appreciated by members of the community, then coordinated action from local citizens may be the only way to save it regardless of artistic merit. While there is a growing recognition of street art, illegally placed artwork is subject to the wishes of the landowner. Whether you agree or not, the legal reality balances the value of art against the value of property rights, and the result is unsurprising. Although it makes sense from a policy perspective, it has also led to the destruction of many important works of art. Copyright law applies to all artwork, legal or otherwise. “Legal” work can have the additional protection of VARA which might prevent certain important works from being lost, or altered, or even exploited improperly. Conversely, artists of commissioned work may be entitled to VARA protections even absent their ownership of the copyright.

Conclusion

Copyright grants artists the right and ability to control the copying and distribution of their work. Murals painted with the approval or the property owner will enjoy this protection under VARA if it meets the necessary subjective conditions. If it’s protected under VARA and if the artist or their agent is attentive, if there is an attempt to alter or deface the work the artists has rights that can stop the artwork from being changed or even repaired without permission. But the artist must assert that right. The artist should be able to assign that right to someone, or an agency, to protect the work like the Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles. That solution hasn’t been tested in the courts, but certainly has been suggested in the cases.

With regard to unpermitted works, the rubbing out, painting-over and alteration by other artists, and the constant changing urban landscape drives street art forward. While such art can be commoditized, it is inherently impermanent. Perhaps today’s mural and street artists owe thanks to the public reaction and the laws that constrain the medium because they force it to evolve.

Read more about VARA rights in this article.