In Janurary 2017, PSAA director Tiffany Conklin took part in a panel presentation at Portland State University that focused on the Intersections of Activism and Effective Nonviolent Action Tactics. This event was hosted by the Peace Action Exhibition & PSU Students United for Nonviolence. The panel sought to explore the intersections of art, protest, and law in making positive change and how people can get involved in creating meaningful and sustainable change. Other panelists included Gregory McKelvey, one of the leaders of Portland Resistance, and Steve Kanter, a Lewis & Clark law professor and former president of the Oregon ACLU. The following is a recap of PSAA's presenation.

The human urge to make art is rooted in our desire to develop and share lasting narratives that reflect, inform, and construct our identities and societies. The making of art is an important and vital part of human evolution. It has served as one of our main modes of communication and culture building. Therefore, art can be used as a “conceptual frame” through which observations and interpretations about society can be explored, and new ideas put forth.

Resistance art often aims to influence attitudes. It interrupts and exposes injustices, mocks and disarms perceived evils, and pushes for collective action against powerful social, political, and corporate structures. Throughout history, it has been a tool for the disenfranchised and disillusioned. In most revolutions, some sort of artistic and creative messaging has helped the movements mobilize and sustain themselves. Social movements require a lot of communication between many of different types of people. In order to reach everyone, these “public consciousness wars” are often fought symbolically and literally in the media, on city streets, and through art and literature.

When analyzing resistance art, one similarity is very clear, it relies heavily on the use of symbols; place holders for larger ideas and shared narratives. However, creating powerful symbols is not easy. Speaking for and representing something significant enough to be meaningful to a community, requires an engagement with deeply embedded symbols in that community, as well as dependency on already agreed upon visual cues.

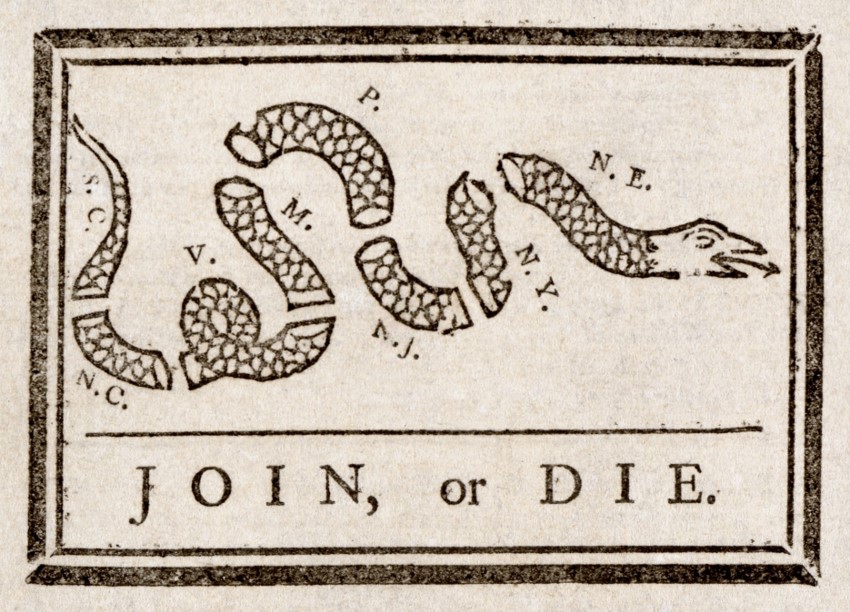

Join, or Die is one of the oldest commonly used symbols of resistance. Originally drawn by Benjamin Franklin in 1754, the cartoon depicts the early American colonies as a snake divided into 8 segments; a representation of colonial unity. Franklin’s ability to develop and disseminate powerful messages like this helped reinforce his influence as an effective communicator.

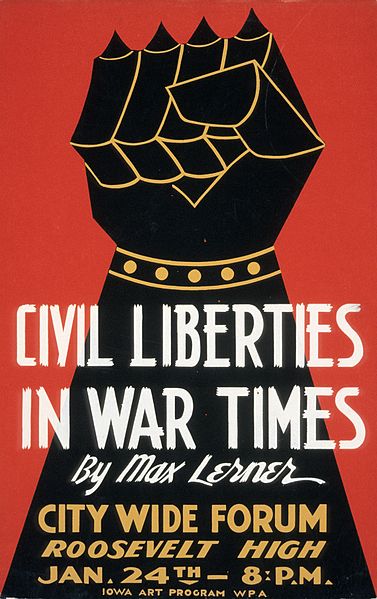

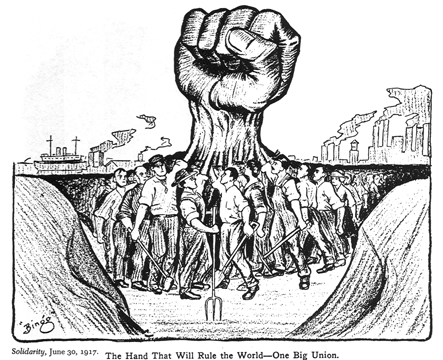

The Resistance Fist dates back to ancient Assyria, where depictions of the goddess Ishtar served as a symbol of resistance in the face of violence. In modern times, the Industrial Workers of the World first used the fist as a logo in 1917. The symbol is now highly recognizable and adopted by oppressed groups around the world, as a symbol of solidarity, strength, and resistance.

The Anarchy Symbol is also well-known. The "A" stands for "anarchy," and the "O" stands for "order;" together standing for "Anarchy is the Mother of Order.” The first recorded use of this symbol was by the Federal Council of Spain of the International Workers Association in 1868.

The Guy Fawkes Mask is another old symbol of resistance, dating back to 1605. This is not just a symbol, it also serves an important logistical purpose. Remaining anonymous can help one evade authorities and continue revolutionary activities. In certain situations, having your identity exposed can put you, your friends, and family at risk. However, this symbols is highly co-opted. It was the top-selling item on Amazon in 2011 and Time Warner owns the rights to the image, so they profit from every sale.

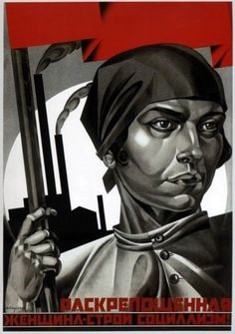

Like resistance art, propaganda art is also a mode of artistic communication, aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position. Since propaganda is often used by political regimes to manipulate people’s emotions by displaying facts selectively and presenting utopian (sometimes false) views of the society, it’s often viewed negatively. For better or worse, over time, propaganda art has had a profound influence on public consciousness. The techniques used by propaganda art are not inherently bad; as it can also be used in a positive way, to relay things like health recommendations, PSAs, and encouraging people to vote.

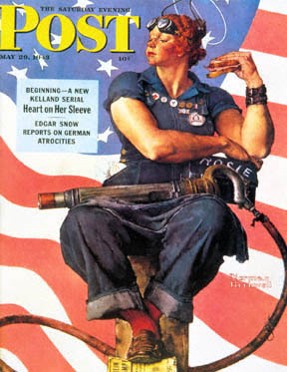

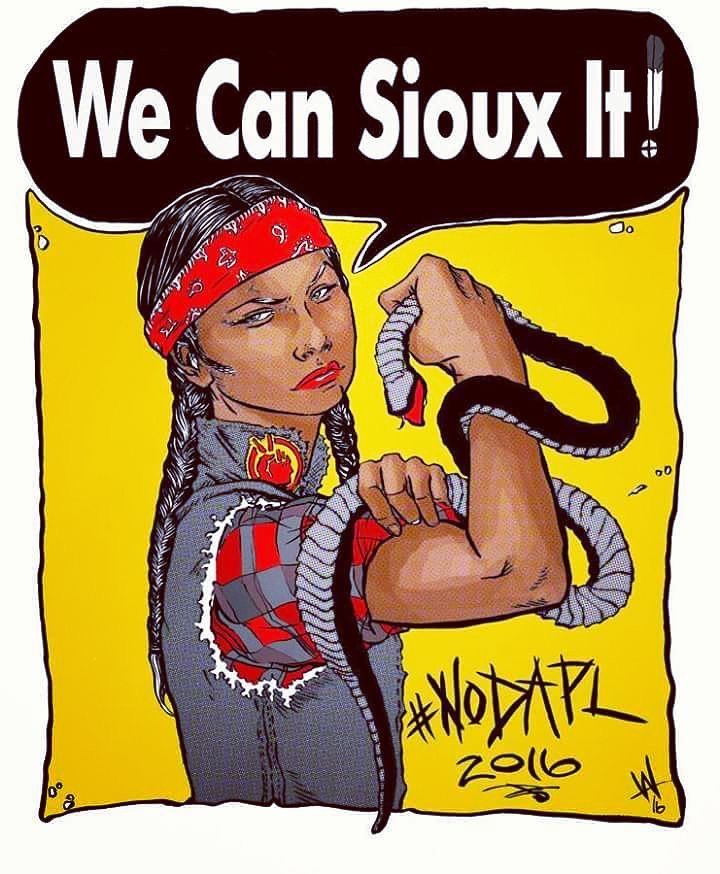

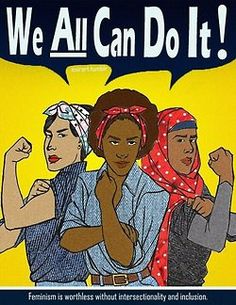

Take for example, the evolution of the We Can Do It poster created by Westinghouse Electric in 1943. Initially, it was used to boost the morale of female employees so they would be more productive. Later in the 1980s, the poster was rediscovered and used to promote feminism. It is often mistaken for Rosie the Riveter, also created in 1943, but by Norman Rockwell. Again, Rosie was a “call to arms” for women to become strong capable females to support the war. Examples of this imagary can be found being used all around the world and continue to be used and adapted today.

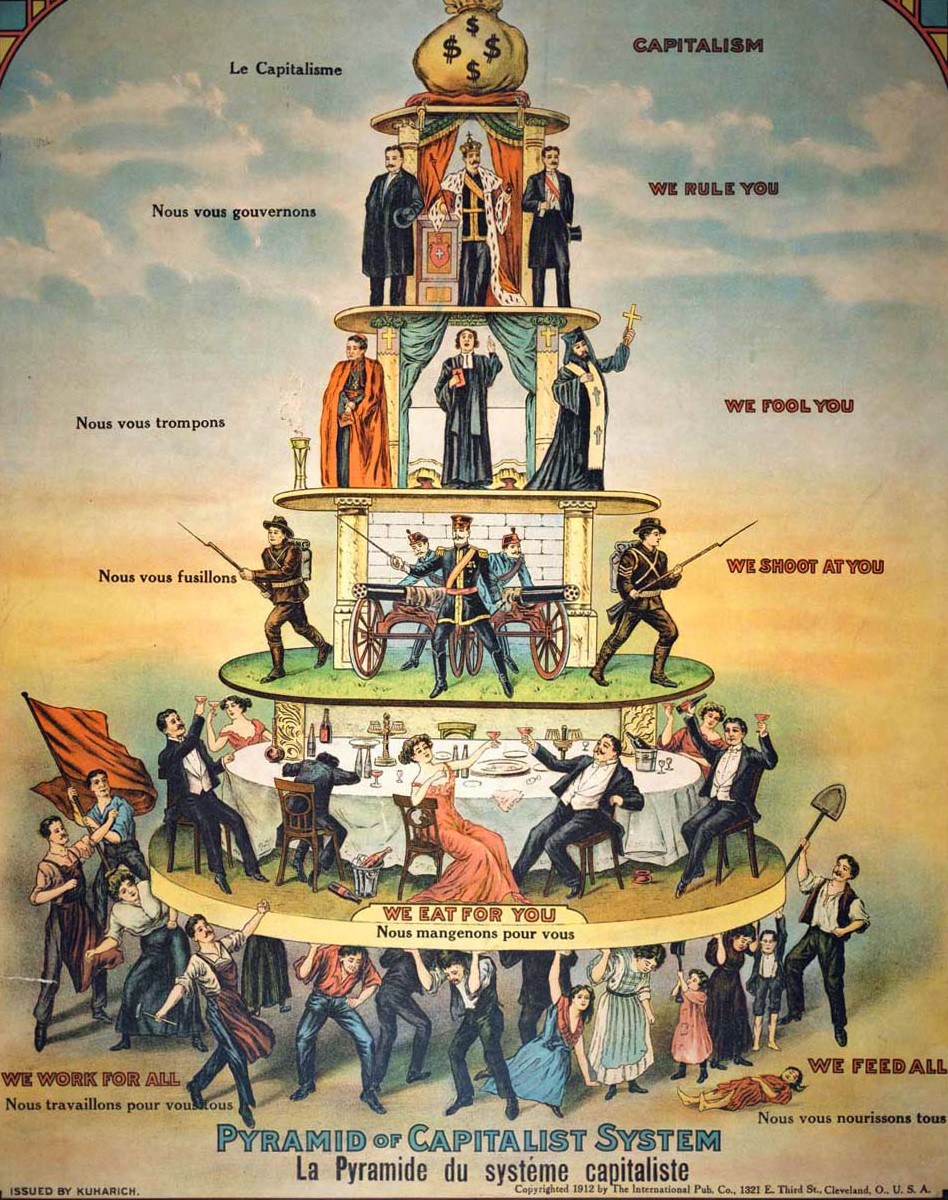

We can also see examples of resistance art in political cartoons and satire art. Many of these cartoons depict harsh commentaries and critiques, encouraging people to question the politics of the time. For example, the Pyramid of Capitalism has been a powerfully illustrative critique of capitalism. Painted in 1911, it depicts a system of social stratification and economic inequality. It is a powerful reminder that if the workers of the world withdraw their support, the system would literally topple over.

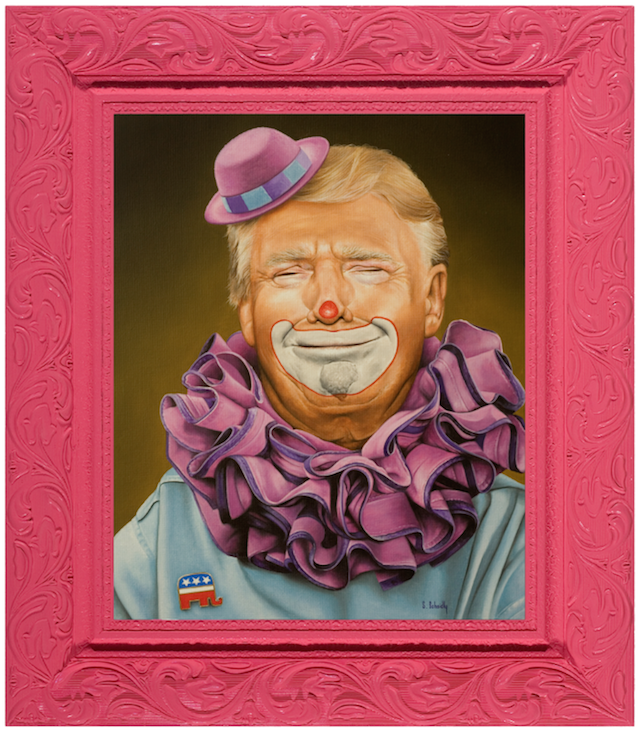

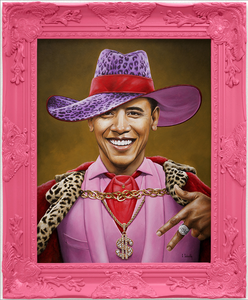

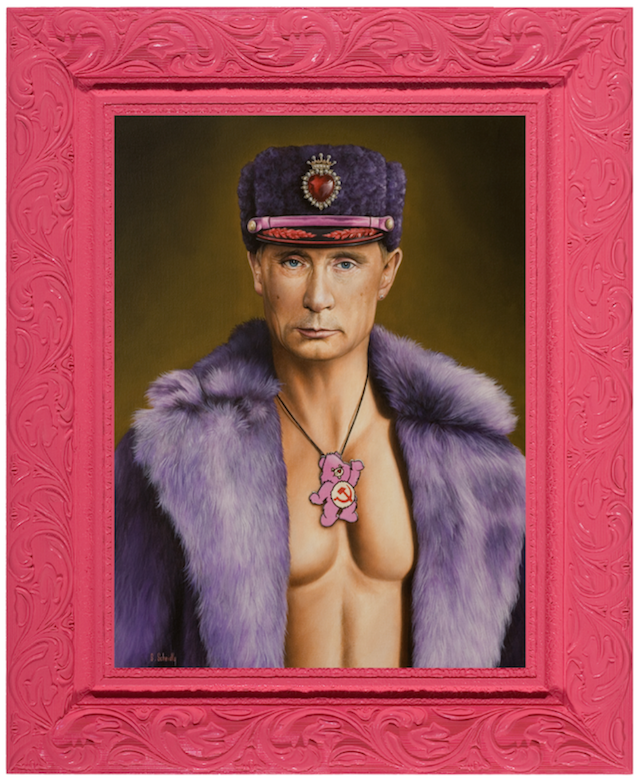

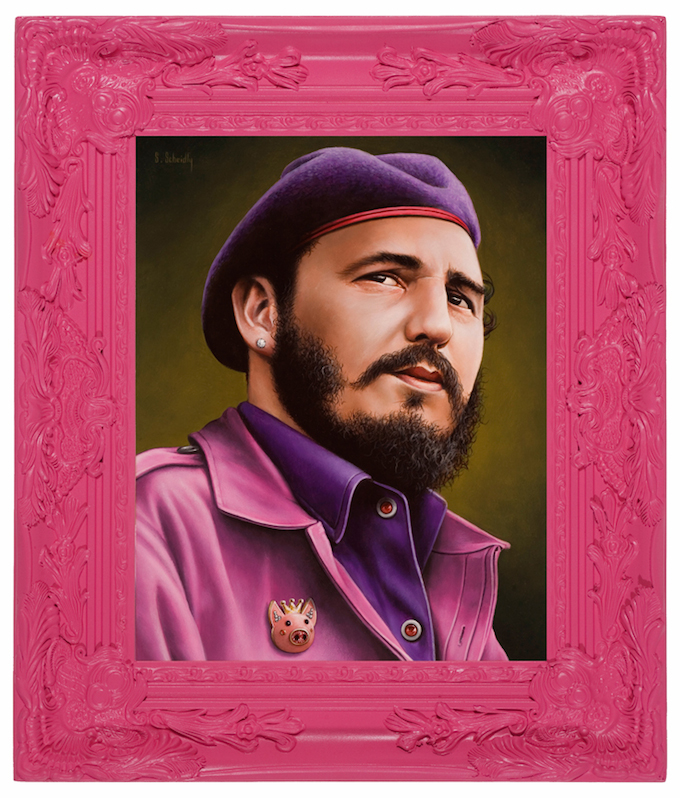

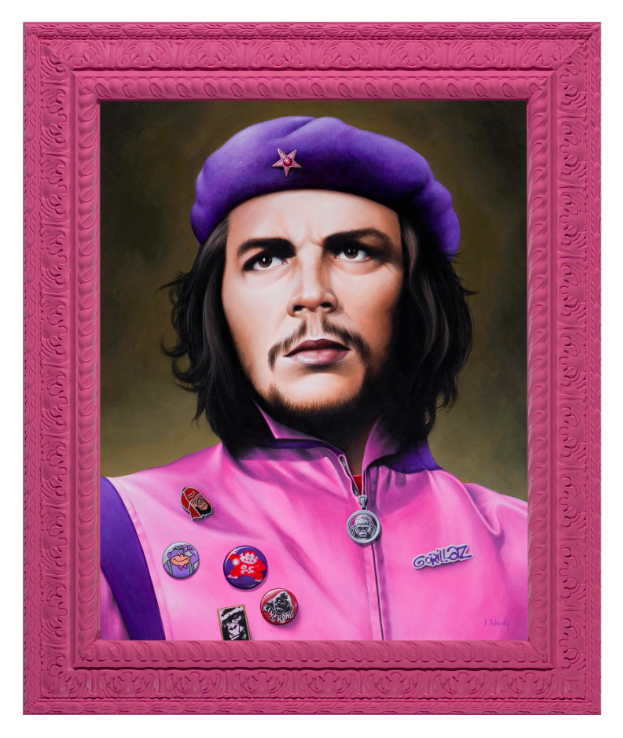

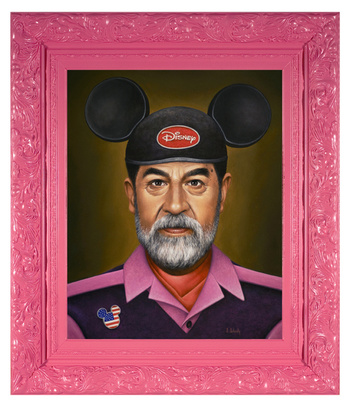

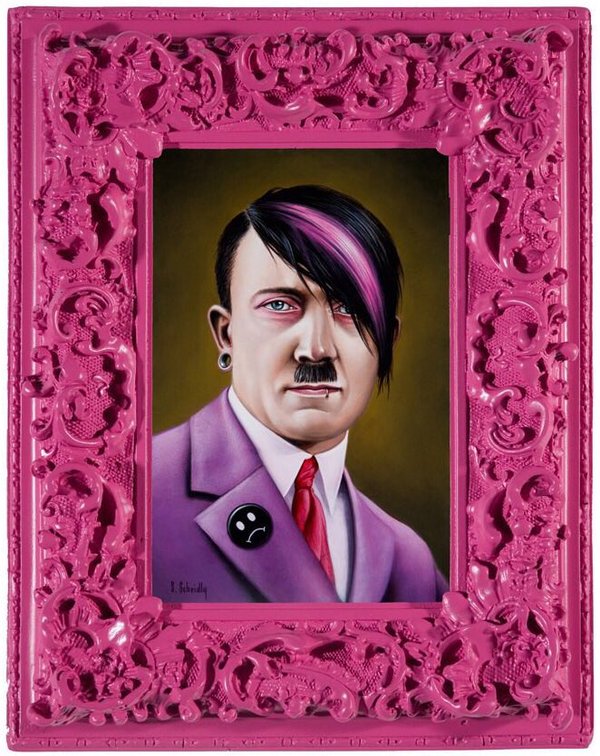

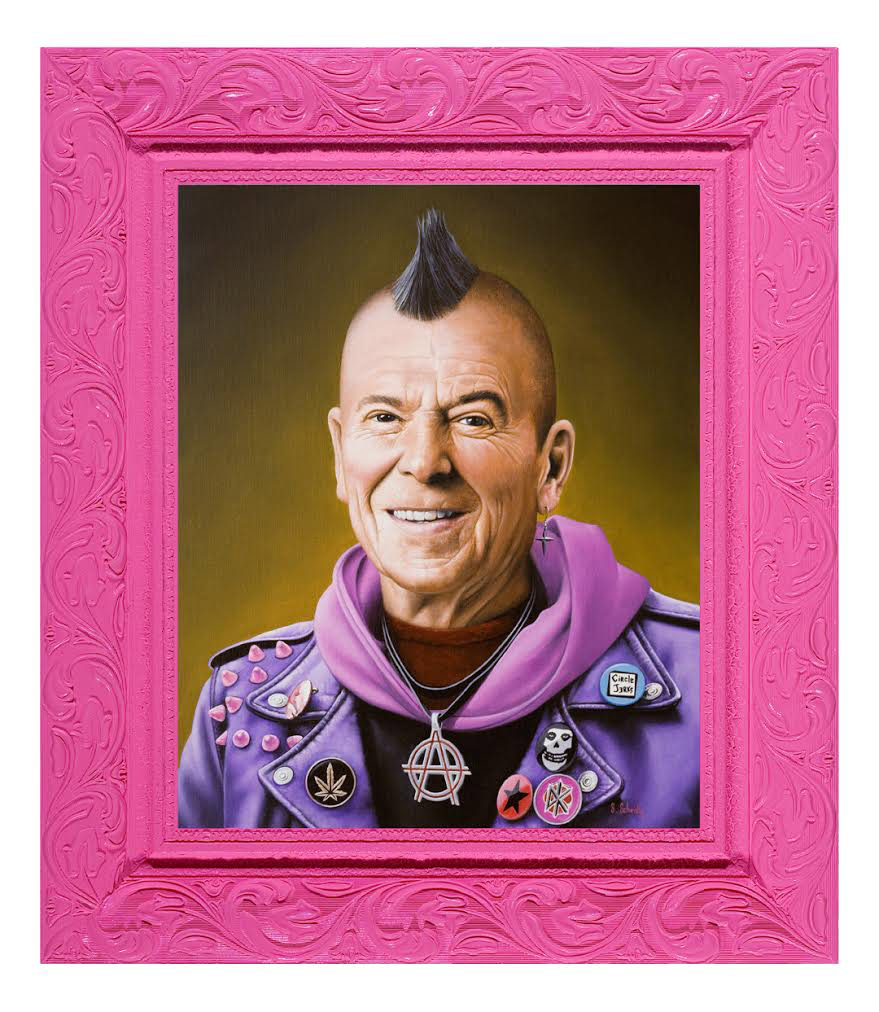

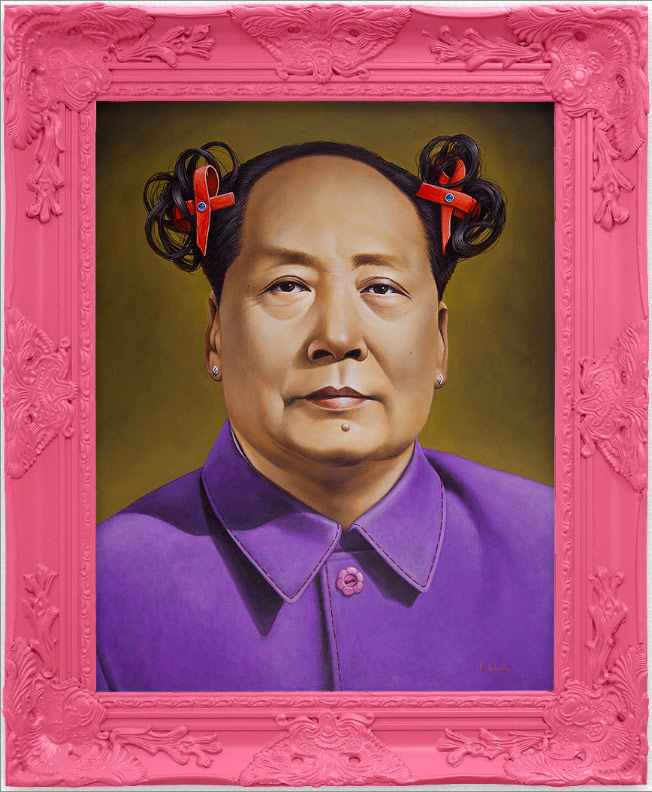

We could also look at many different types of examples of resistance being made in the fine arts. For example, the post-apocalyptic worlds by Scott Listfield, or the satirical portraits of world leaders and dictators by Scott Scheidly (photos above). It is important to remember that galleries and museums have more limited access than public space, so while it can be powerful, this art may only reach more privileged urban audiences.

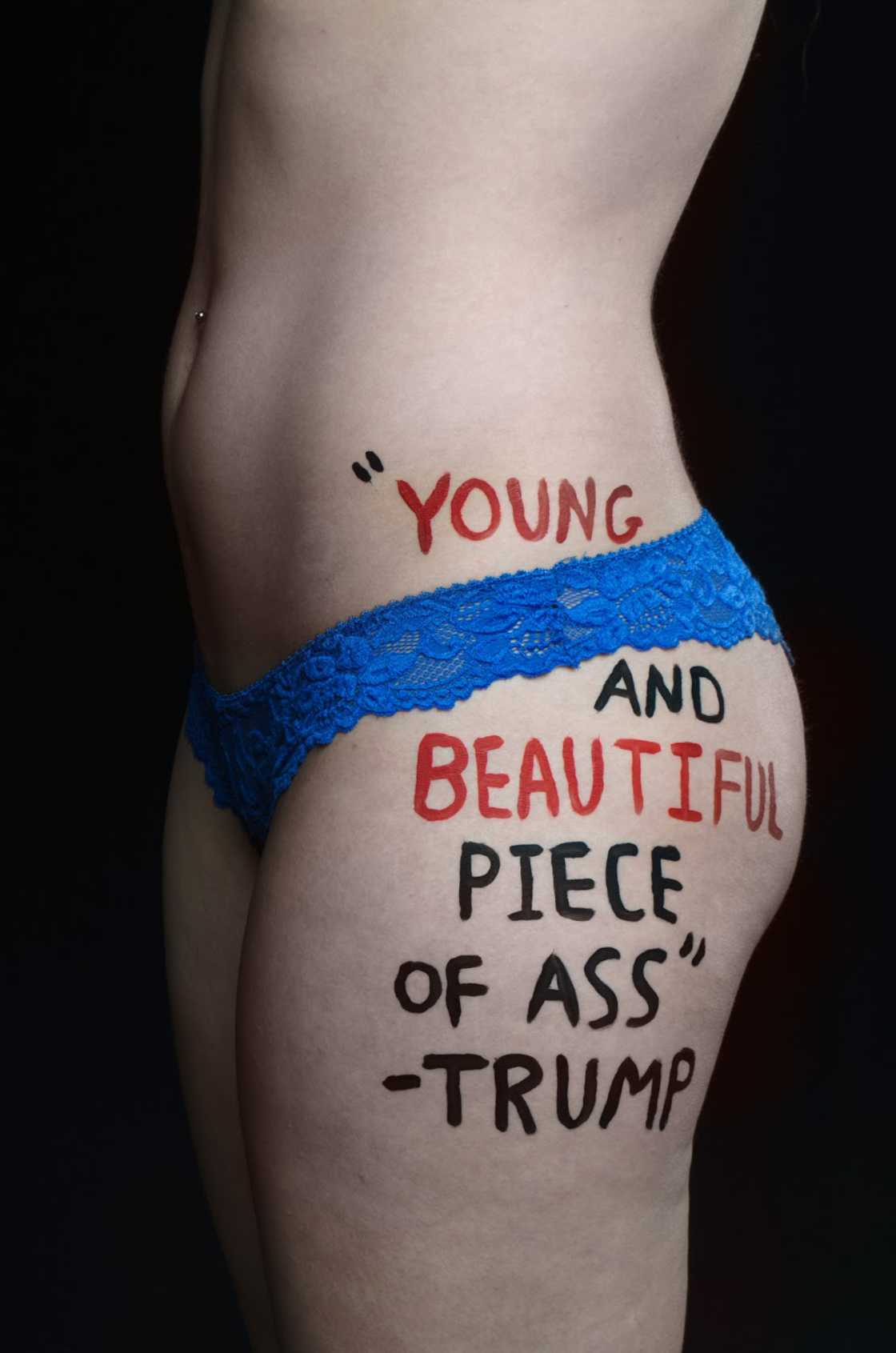

Photography can also be used for activism. For example, in 2017, an Oregon community college student created her #SignedByTrump project for a photography class using Donald Trump quotes painted on mostly nude female bodies. These photos went viral right before the 2017 presidental election. Or the photography of Portland-based Yay PDX, a local activist documenting protests and our city’s houseless population.

Light Installation, Portland Oregon

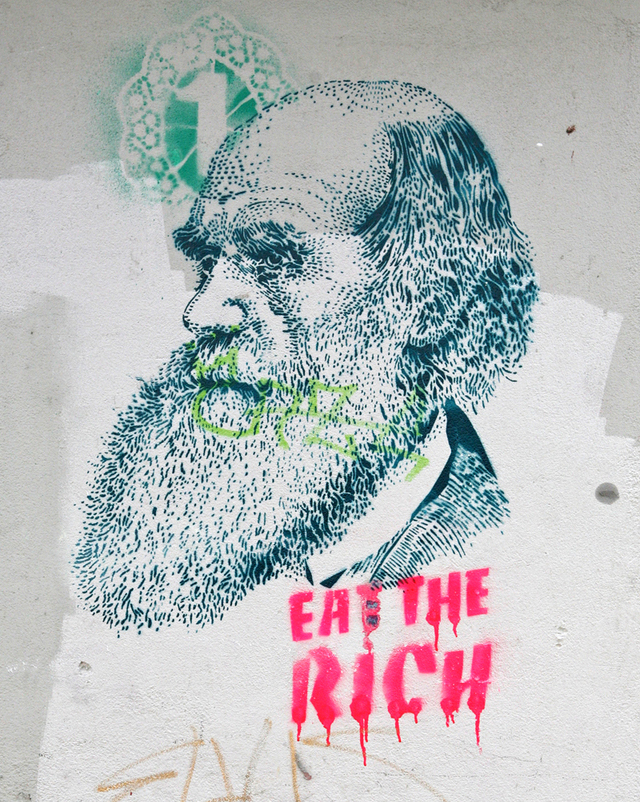

One of the most influential places where art can make a profound impact is when it’s placed in public space. Whether its scribbled, scribed, pasted, placed, painted, or acted out; our city’s public spaces have always been a hub for expression and communication. They are, after all, the original arena for free expression and democracy. Graffiti and other types of urban interventions are a way to freely, automatously, and democratically communicate with each other, regardless of social or financial standing. You can reach a lot of different types of people, they just need to be passing by. You don’t need to have enough money to pay for a billboard or TV ad to get a message across.

Public art provides a space for representation; a way to expand reach and amplify voices. If the embedded message is particularly relevant and powerful, people will take photos of it, it will end up on the internet and in social media, where its reach is almost infinite and it will live on forever, even if it’s removed from public space. Another important thing to realize is that during revolutions, governments not only increase their surveillance of public and online spaces. They will often shut down social media and limit internet access (like they did in Egypt and Greece recently). In these instances, we’ve seen graffiti used as a way to continue to communicate dissenting ideas, agitations, and instructions. Recently, social movements like Hong Kong's Umbrella Revolution, Standing Rock, the Egyptian Revolution, and the Black Lives Matter Movement have all employed art to further their cause and spread their messages.

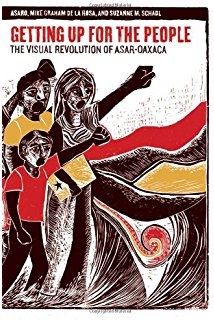

In certain cities, entire organizations have formed around the focus of making and promoting resistance art. Perhaps one of the best examples is the Assembly of Revolutionary Artists of Oaxaca. ASARO teaches art workshops for young people from Oaxaca’s impoverished districts and encourages them to translate their histories, perspectives, and social grievances into creative visual exchanges with others. They make stencils, woodcuts, wheatpastes, flyers, and public installations. They teach classes at their studio, hold meetings, maintain blogs & active social networks. By disrupting urban spaces with contradictory messages of conflict, they help to reveal inconsistences between the state’s manufactured image and the actual experiences of the people. The art they support helps summarize the critical force that comes from the periphery, to resist authoritarian political structures and capitalist economic priorities. These pieces invite viewers to stand up with the artists and participate in transforming their social realities together.

By disrupting urban spaces with contradictory messages of conflict, ASARO helps to reveal inconsistences between the state’s manufactured image and the actual experiences of the people. The art they support helps summarize the critical force that comes from the periphery, to resist authoritarian political structures and capitalist economic priorities. These pieces invite viewers to stand up with the artists and participate in transforming their social realities together.

Resistance art has had a profound influence on public consciousness throughout human civilization. It plays an indispensable role in the formation of public discourses, representation, and our struggles towards democracy. The best art challenges us to think differently, provokes our emotions, and encourages healthy debate with others. In uncertain times, when economic, social, and political systems fail to support society, art and graffiti serve a vital function of communicating grassroots ideas, sympathies, and demands.