ENTER AT YOUR OWN RISK:

THE HISTORY OF PIRATE TOWN

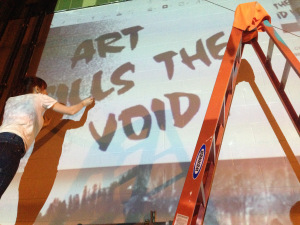

Everything is ephemeral. Sometimes it takes loosing cherished pieces of our city to realize what is important and how change is the only constant, especially in a city. As Portland’s wild-west development bonanza booms, many of us are hard at work documenting and fighting to save these important pieces of the urban landscape.

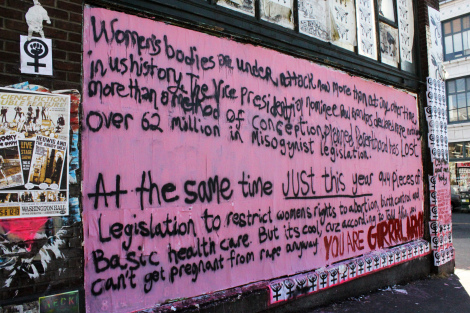

Our urban growth boundary helps preserve our hinterlands and create a dense city, but it also ensures that vacant space is temporary and abandonment is short-lived. As in other cities, Portland is growing at an unprecedented rate due to the millennial desire for a more sustainable urban life. With this influx, comes change and with this change there are important considerations and sacrifices. What impact does the loss of free, hidden, and accessible spaces have on the city and its arts culture?

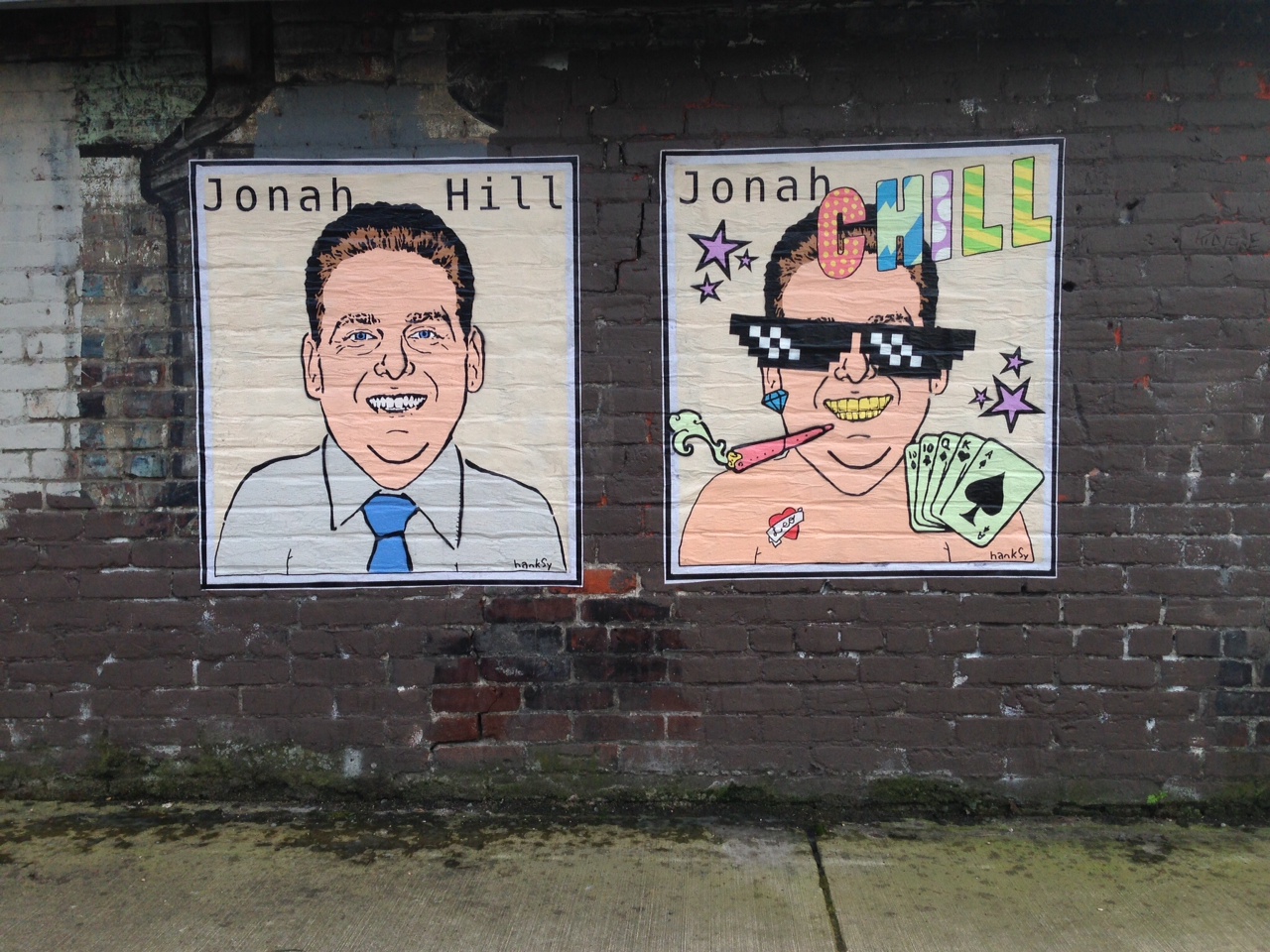

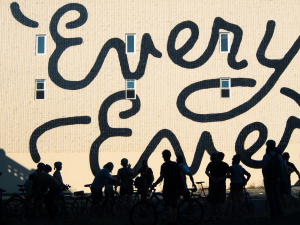

Indeterminate “spaces in-between” are voids in the city, undesirable to most people and sought after by some. These abandoned, contaminated, and sometimes dangerous spaces are where DIY activities flourish. Whether it be for graffiti art, skate/BMX parks, urbex, or guerilla gardens, these “cracks” in the urban fabric provide respite from norms and regulations of modern urban space. These spaces are open to possibilities for intervention and ripe for activation; places where the seeds of innovation and authenticity can be sown.

As we contest and cope with our changing city, it is important to document and remember an important piece of Portland’s DIY and graffiti history that is quickly fading into distant memory.

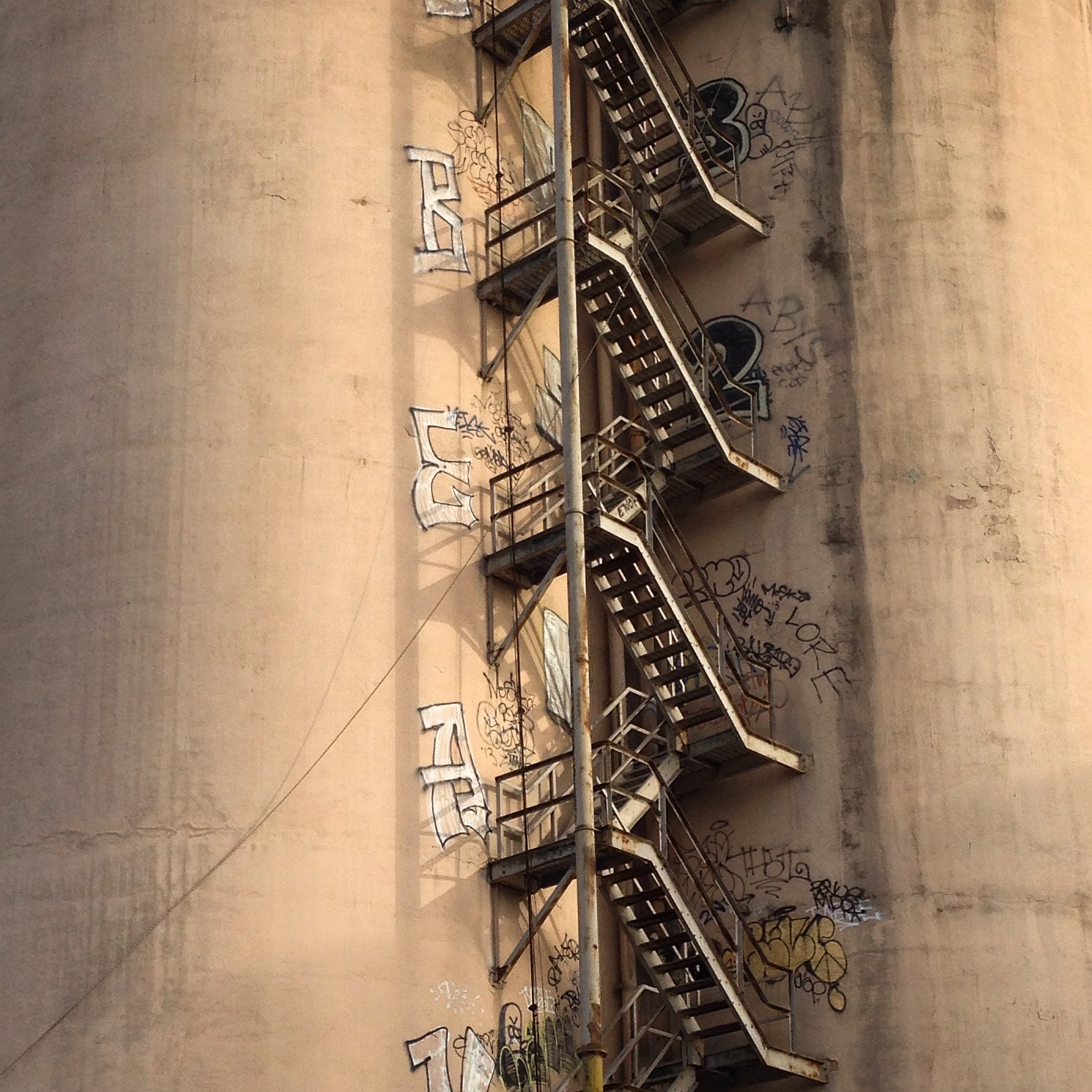

It was known by many names: Popsicle Land, Creosote Factory, SuperFun Site, officially named Triangle Park, and most infamously Pirate Town. This 35-acre superfund site is situated on the Portland Harbor at the base of Waud Bluff and in the University Park area of North Portland. With an industrial history dating back to at least 1900, this site has been home to nearly 50 different industrial operations.

Photo: Michael Endicott

Photo: Michael Endicott

Most recently, this was the site of the former Riedel North Portland Yard, which dredged rivers, constructed boats, and cleaned-up hazardous railroad spills. Riedel closed in 1986, but the effects of its operations (and the site’s prior operations) will be present for centuries to come; as soil and groundwater tests show high levels of toxic contaminates, mainly arsenic.

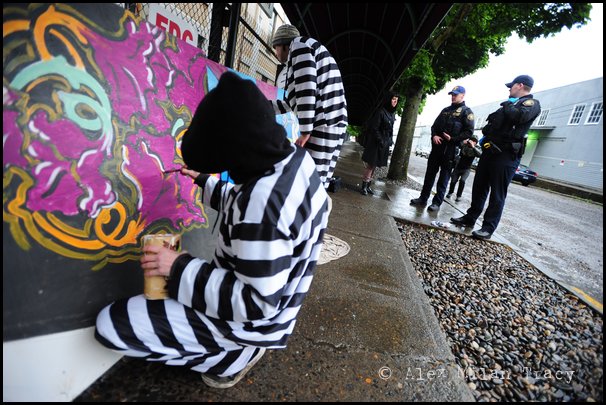

This abandoned complex consisted of a dock and three cement buildings. The site provided both a canvas for the most prolific graffiti in Portland at the time and space for creation of DIY skateboarding and BMX structures. Skaters and BMX riders revamped Pirate Town, turning the spaces into parks reminiscent of the early Burnside Bridge days. For years, Pirate Town was a cherished space for all sorts of adventure; a place to end midnight bicycle rides, hold massive parties, host an epic chariot wars, army training ground, and a horror movie theater.

Photo: The Skateboard Archives, skateandannoy.com

A 2009 Portland Mercury article by Sarah Mirk documented the public sentiment when demolition plans were announced: “It’s one of those places where there’s no rules. I’m perpetually frustrated by how society stomps out the places where people can create new things,” Zander Speaks told reporters. Similarly, Zachary van Buuren said that it was “one of the few places that graffiti artists could go to do their art and it’s completely alright. It’s a giant industrial canvas, sad to see it go.” Gabe Tiller who rode around town on a coffin bike, explained that “these urban decay areas are gorgeous and every city needs them, it was inevitable I guess. Fun while it lasted, and there are other great spots out there waiting to be found!”

Photo: Jeremy Running

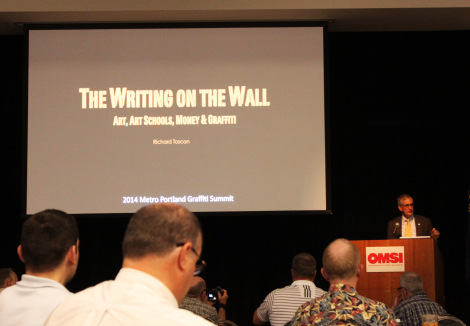

American Institute of Architects even hosting a photography show displaying the work of Bruce Forster, commemorating the graffiti that covered almost every inch of the structure.

Photo: Chris Nukala, theskateboardarchives.com

Reminiscing about the Pirate Town 10 years later, native Portlander and professional BMX rider Caleb Ruecker explained to PSAA that for many years it was a favorite spot for him and his friends, for not only biking but fishing off the decaying old docks. For a long time it was a chill spot, mainly just used by the bikers, skaters, and graffiti artists, and sometimes visited by photographers and explorers. Then around 2003 nearby University of Portland students started going down there more, even driving their cars down the access road (unlike most who took the back way in along the tracks). This brought a lot of attention to the site and then there were fences and guards.

Photo: Sam Policar

Photo: Bruce Foster

In December of 2008, the University bought the site for $6 million and swiftly demolished it; releasing a statement saying that it was a liability. Back then, UofP representatives explained that the site would allow them to “expand without going into the neighborhood.” They saw this as an “opportunity to take blighted and contaminated industrial land and restore it under the stewardship of the University of Portland as a public asset.” Rumors circulated that it was going to be developed it into a baseball, sports field, or storage area. Today, over 7 years after its demolition, some environmental restoration has happened, but the site still sits completely vacant, being almost completely reclaimed by nature.

Interestingly, the University’s comment about how they intended to restore the site into a “public asset” raises the question about who this development is for, and how the divergent values placed on spaces. These abandoned spaces are actually often being well-used, just not in traditional, scripted, or city-sanctioned ways. While technically being private property, many times these types of sites are left to rot, especially turning into semi-public spaces.

Photo: Chris Nukala, theskateboardarchives.com

These spaces are then reclaimed by certain subcultures and turned into unique “community asset.” However, the general ethos does recognize the value in these unique DIY spaces in cities, they just assume that they are blighted, debauchery-ridden cesspools that need to be removed. True in some cases yes, but in others they are just removed for the sake of removing them, paved or grassed over, or left to sit for another few decades until market demand rises to the point of profit.

Photo: Brandon Seifert

Photo: Aaron Rabideau

As urban planners strive to design authenticity in our cities with placemaking and tactical urbanism-inspired plans, we ignore and disregard the fact that original and authentic place-making is done by the communities like these, in places like Pirate Town and more recently in Taylor Electric. Toxic wastelands flourish into meccas for activity, adventure, and raw beauty. Enter at your own risk.

Special thanks for Caleb Ruecker for providing invaluable insights and inspiration for finally writing this article. Be sure to follow his demolition and abandoned documentation adventures @calebrueckersphotos.

Photo: Aaron Rabideau

Photo: Bruce Foster

Photo: Michael Endicott

Photo: Michael Endicott

Photo: Michael Endicott

Photo: Michael Endicott

Photo: Michael Endicott

Photo: Michael Endicott

Photo: Michael Endicott

Photo: Brandon Seifert

More Pirate Town Photo Albums:

All Photos Tagged with Pirate Town on Flickr

If you have photos of Pirate Town that you would like to share with PSAA, please email us at pdxstreetart@gmail.com.

![Jessica and Jenny dress up downtown’s deer. [Photo by: Travel Portland]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1475722286013-CH04PFRIW9V7RKU22Z3P/Jessica+and+Jenny+dress+up+downtown%E2%80%99s+deer.+%5BPhoto+by%3A+Travel+Portland%5D)

![UglySweaterPDX 2014 [Photo by: Gina Murrell]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1475722319879-L46UH97OBUGHTGK6B6II/UglySweaterPDX+2014+%5BPhoto+by%3A+Gina+Murrell%5D)

![Claudia knits on some leg cozies [Photo by: Jaime Valdez]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1475722364327-ZFZ5AA2RI070N7BGIWJU/Claudia+knits+on+some+leg+cozies+%5BPhoto+by%3A+Jaime+Valdez%5D)