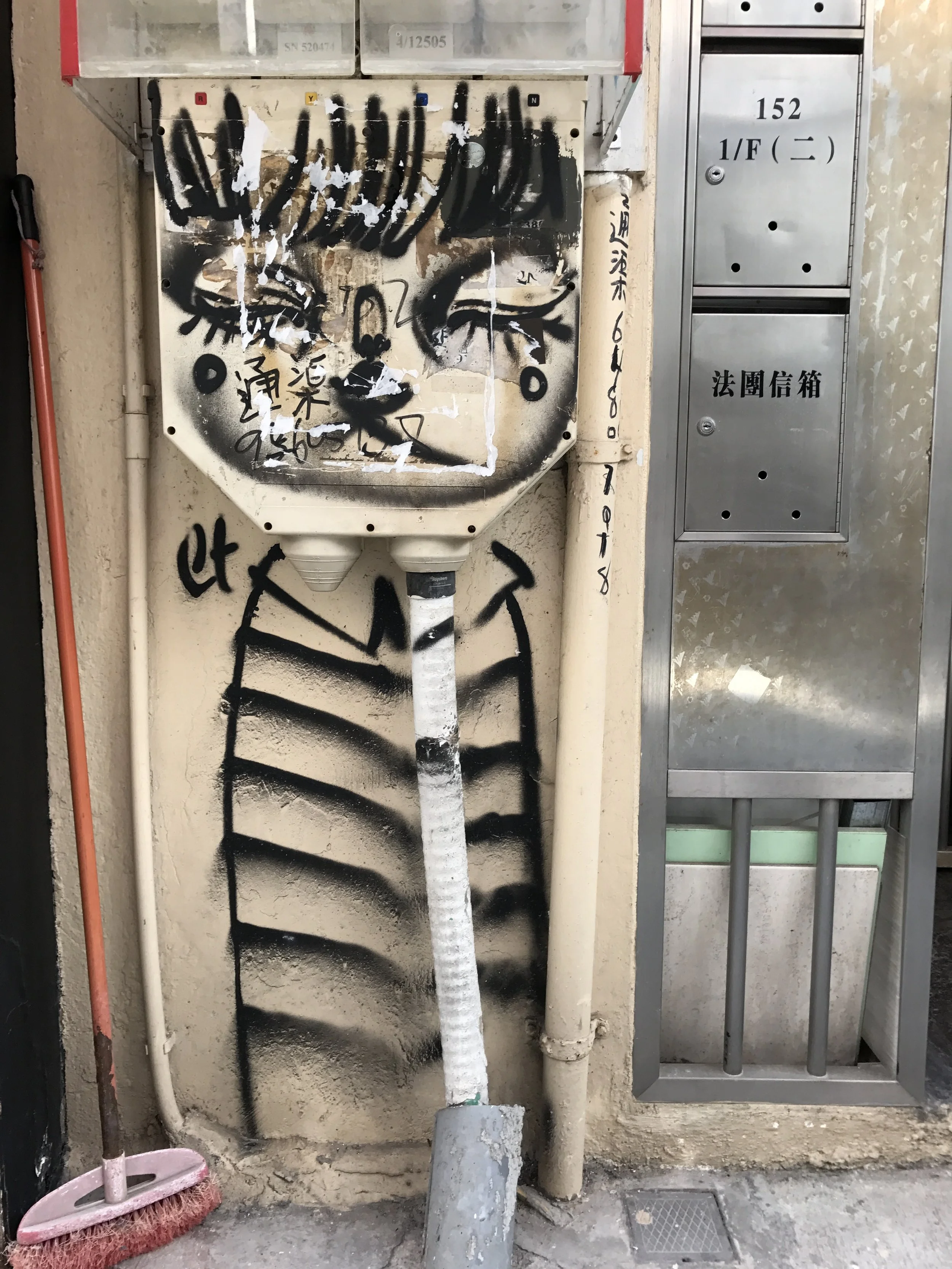

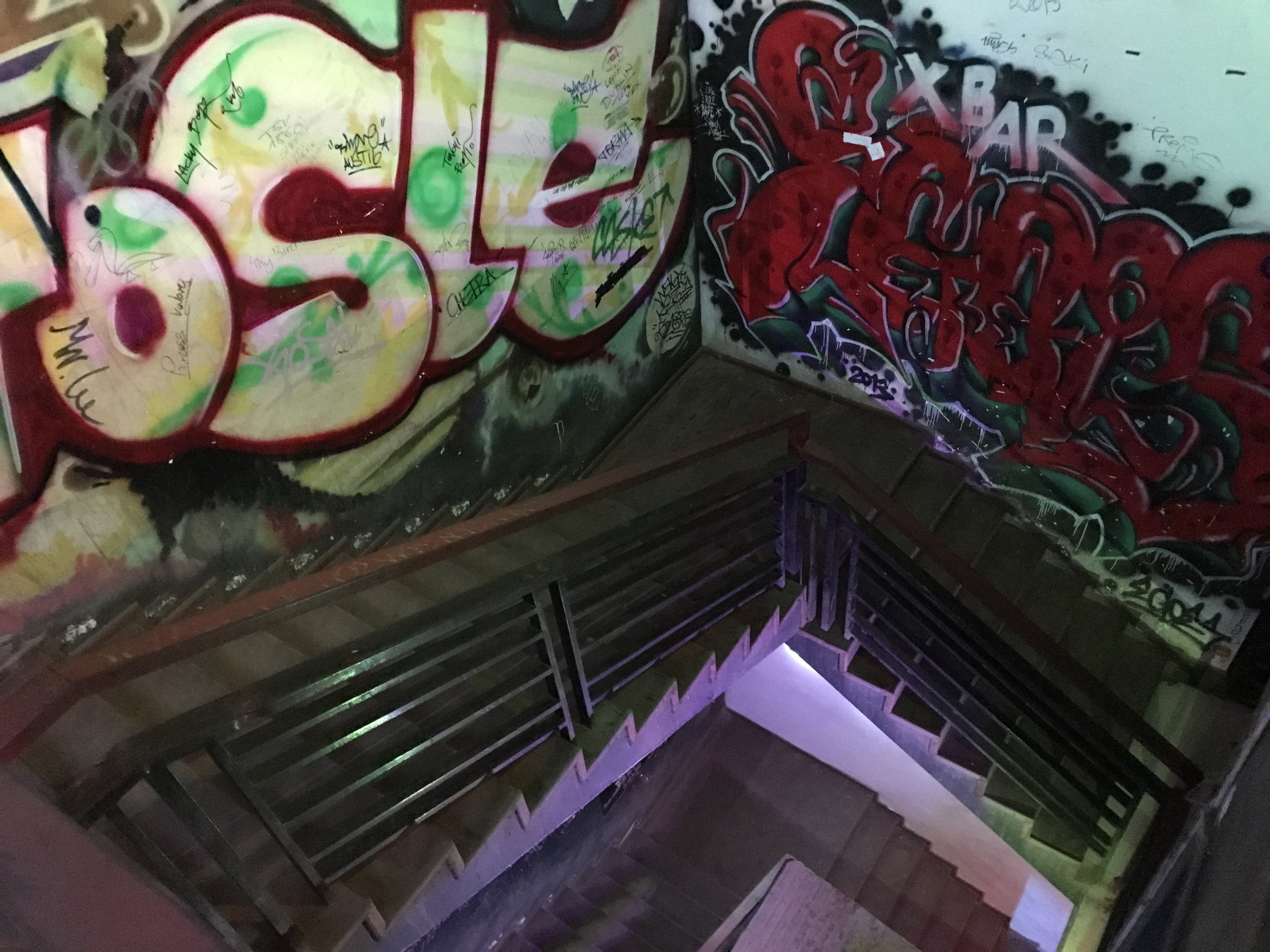

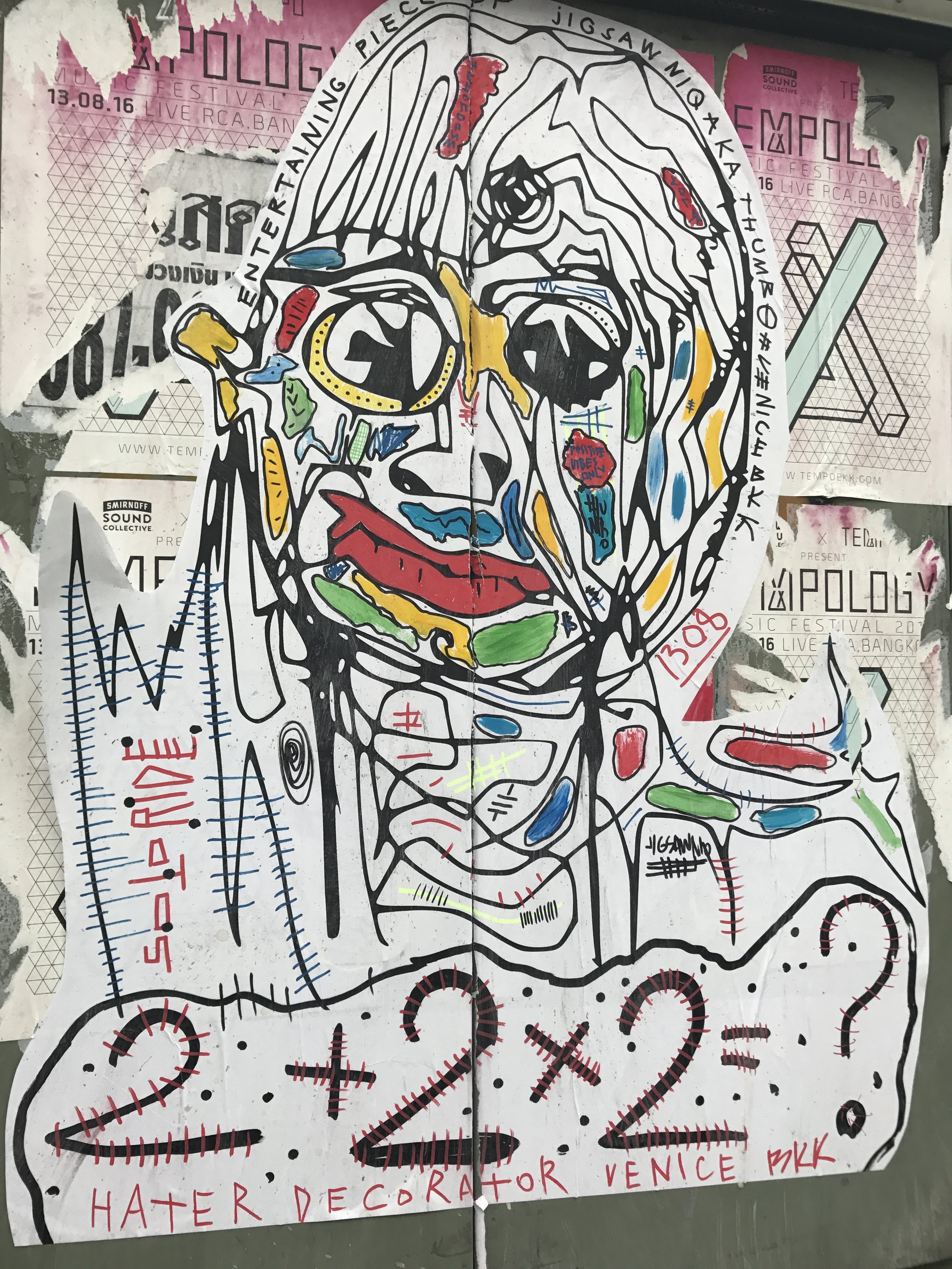

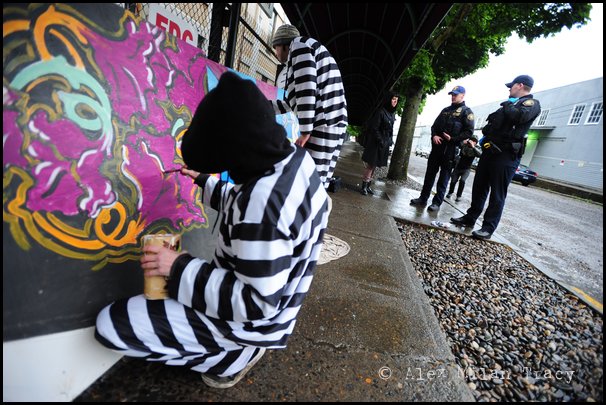

Spicer presented her research on graffiti subcultures and juvenile risk predictors. Her main argument was that graffiti is an at-risk youth indicator and leads to serious social-ills like drug abuse, theft, and violence. Spicer believes that the motivations behind graffiti are usually to vandalize and destroy, and not making art. Spicer sees graffiti as the only supposed “art” movement that produces a victim, and thus needs to be criminalized.

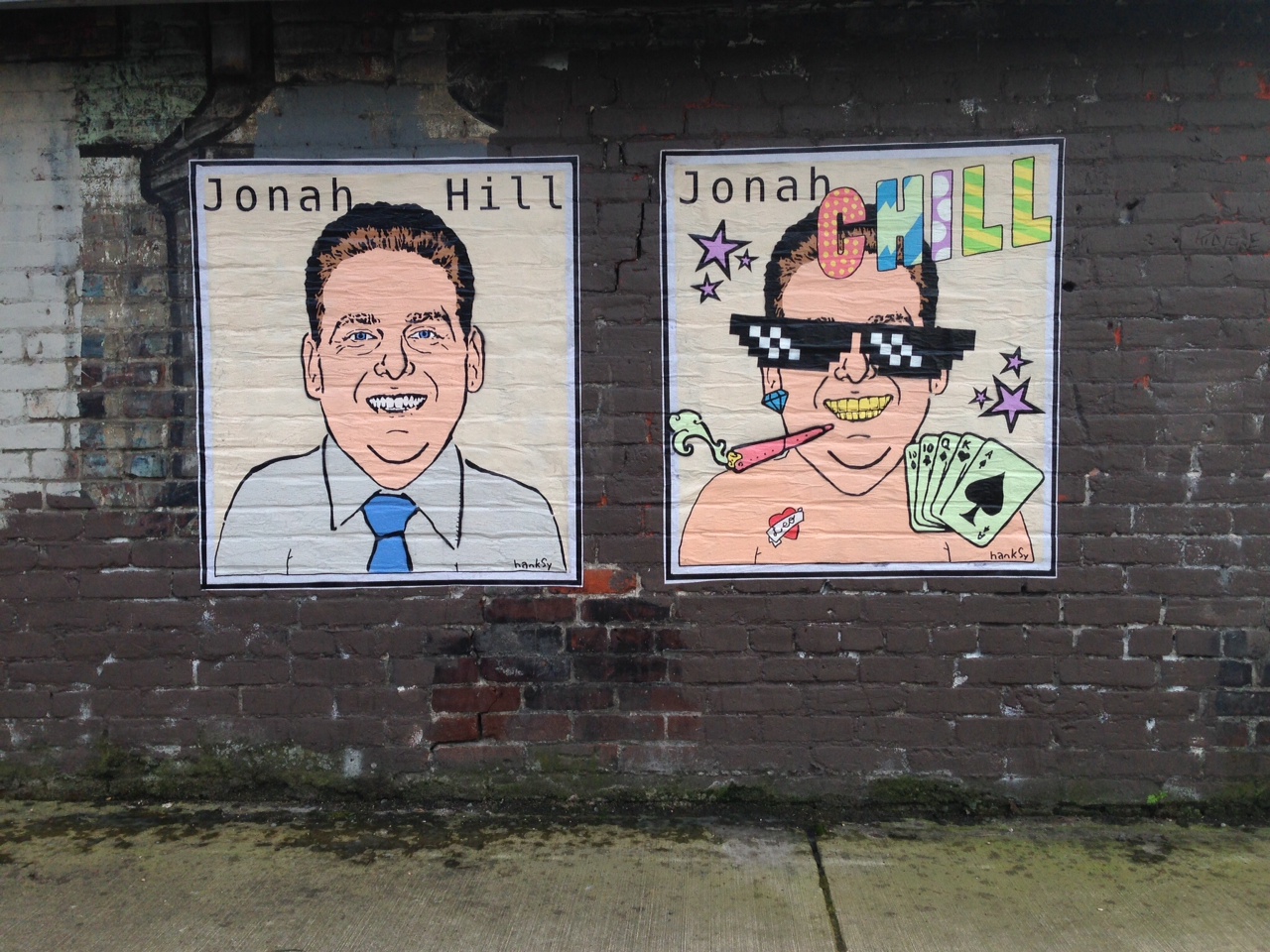

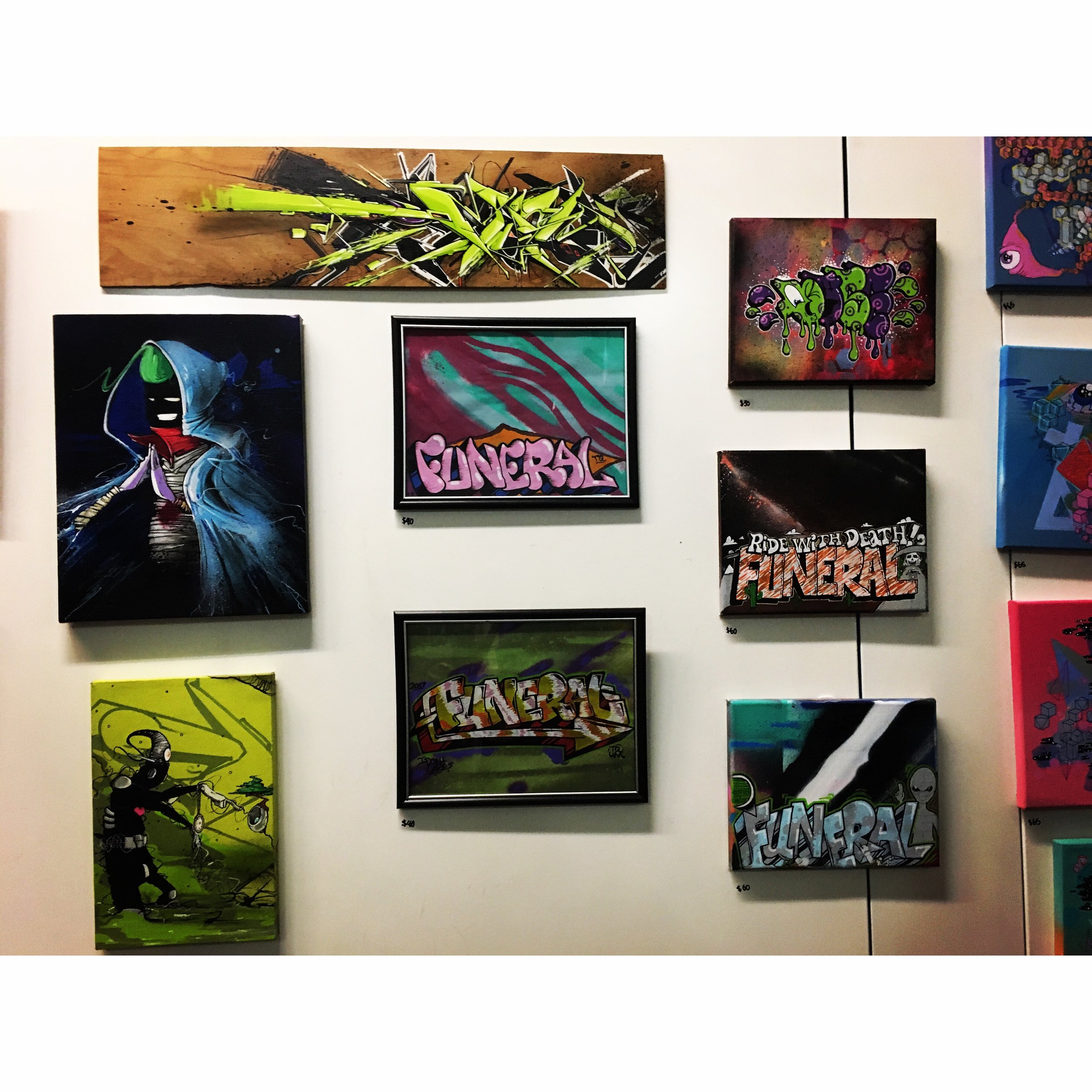

An aesthetical argument was also put forth as Spicer went through photos of fine artists’ work (such as Picasso and Monet), and compared those to the artwork of graffiti taggers at the same age. Her key argument was that the “quality” of work by the graffitists was inferior to that of fine artists.

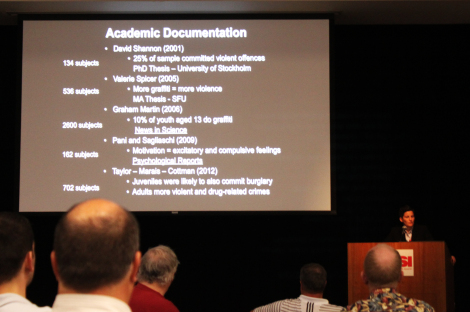

Spicer did present some empirical data from larger studies, like that of Graham Martin (2003), who argued that if society really wants to reduce graffiti, it has the responsibility to address the underlying socio-economic issues causing graffiti and should not just criminalize the outcome. Graham believes these issues should be addressed through preventive approaches and proactive programs, not with increased penalties and criminalization.

Taking just one audience question, Spicer was asked: Do stricter laws result in less graffiti? Spicer said that in Australia and Canada (where her research is focused), current data suggests that harsher penalties do not deter graffiti.

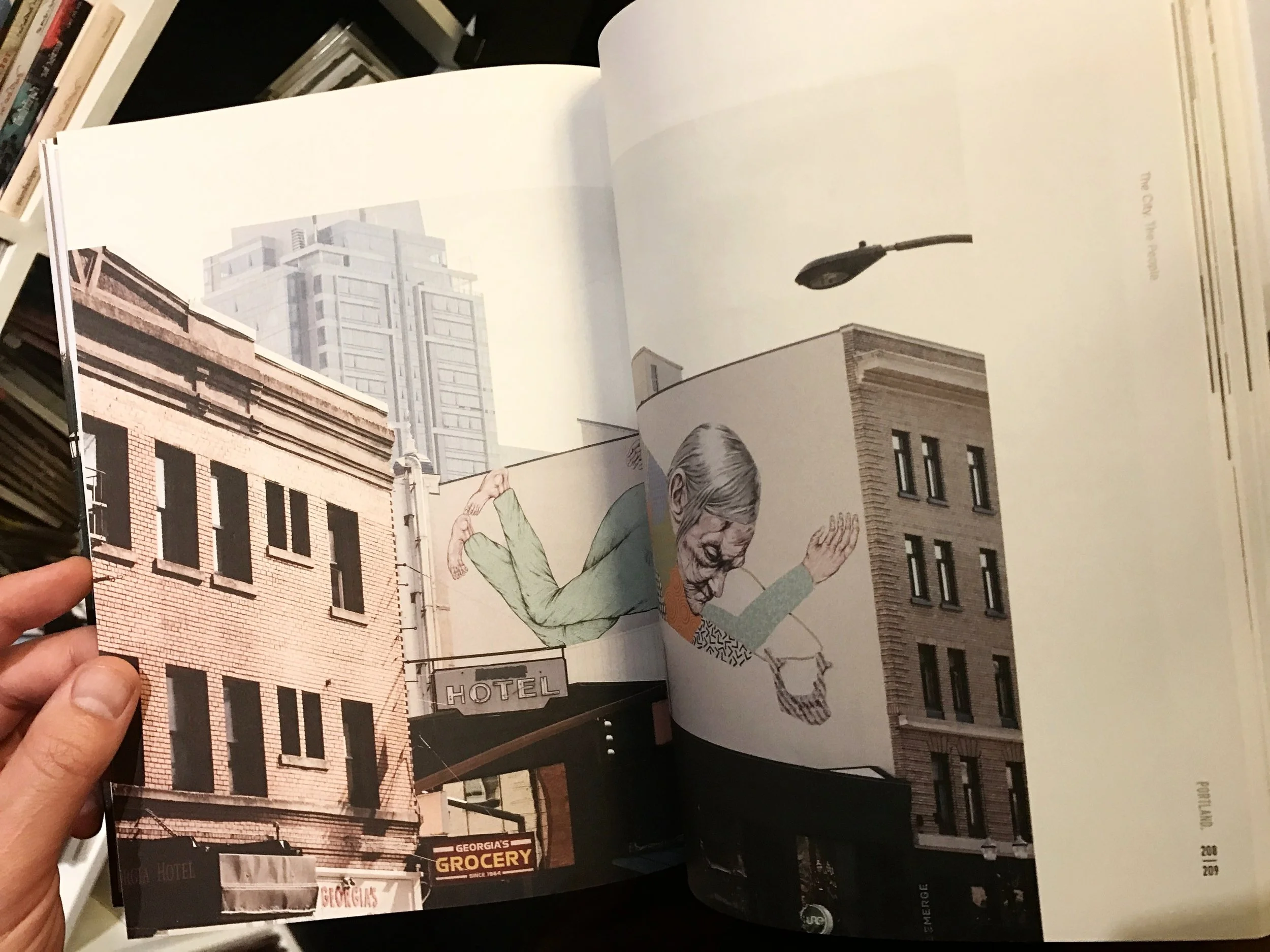

The next speaker was Richard Toscan, a retired art school Dean from Virginia Commonwealth University who helped create downtown Portland’s Cultural District.

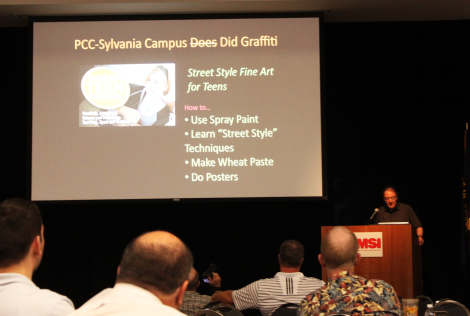

Toscan’s presentation, titled “The Writing on the Wall: Art, Art Schools, Money and Graffiti,” touched on a number of topics, including the Spraycopter (a DIY graffiti-spraying drone), the Pearl District’s Centennial Mills water tower (AKA Portland’s unofficial graffiti museum), and his personal quest to convince the Portland Art Museum not to sell the “Guerilla Art Kit” book.

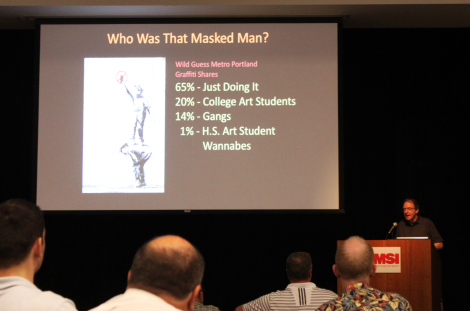

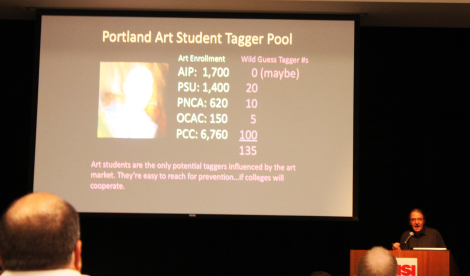

Providing his overview of graffiti art cultures, Toscan focused on street artists who also attend art school. Toscan gave several self-proclaimed “wild guesses” of who might makeup Portland’s “Tagger Pool.” He guessed that there are currently 700 taggers in Portland, 20% of those are “art school students,” and 1% are just “art-school-wannabees.” Toscan’s opinion-statistics went as far as estimating how many graffiti writers come from each of Portland’s universities and colleges.

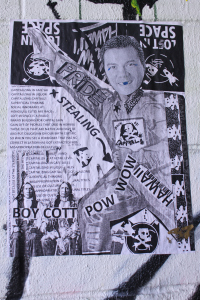

Toscan then called out several Portland street art and graffiti related organizations and initiatives. Included in his list, was the Portland Street Art Alliance, labeled the “The Second Front: The Graffiti Lobby.”

Toscan told the audience to ignore PSAA’s mission statement (describing it as meaningless academic jargon) and explained that what PSAA is really doing is promoting crime, destruction, and vandalism. Toscan went on to suggest that PSAA was consorting with the Regional Arts and Culture Council (RACC) and will soon receive operational funding from them.

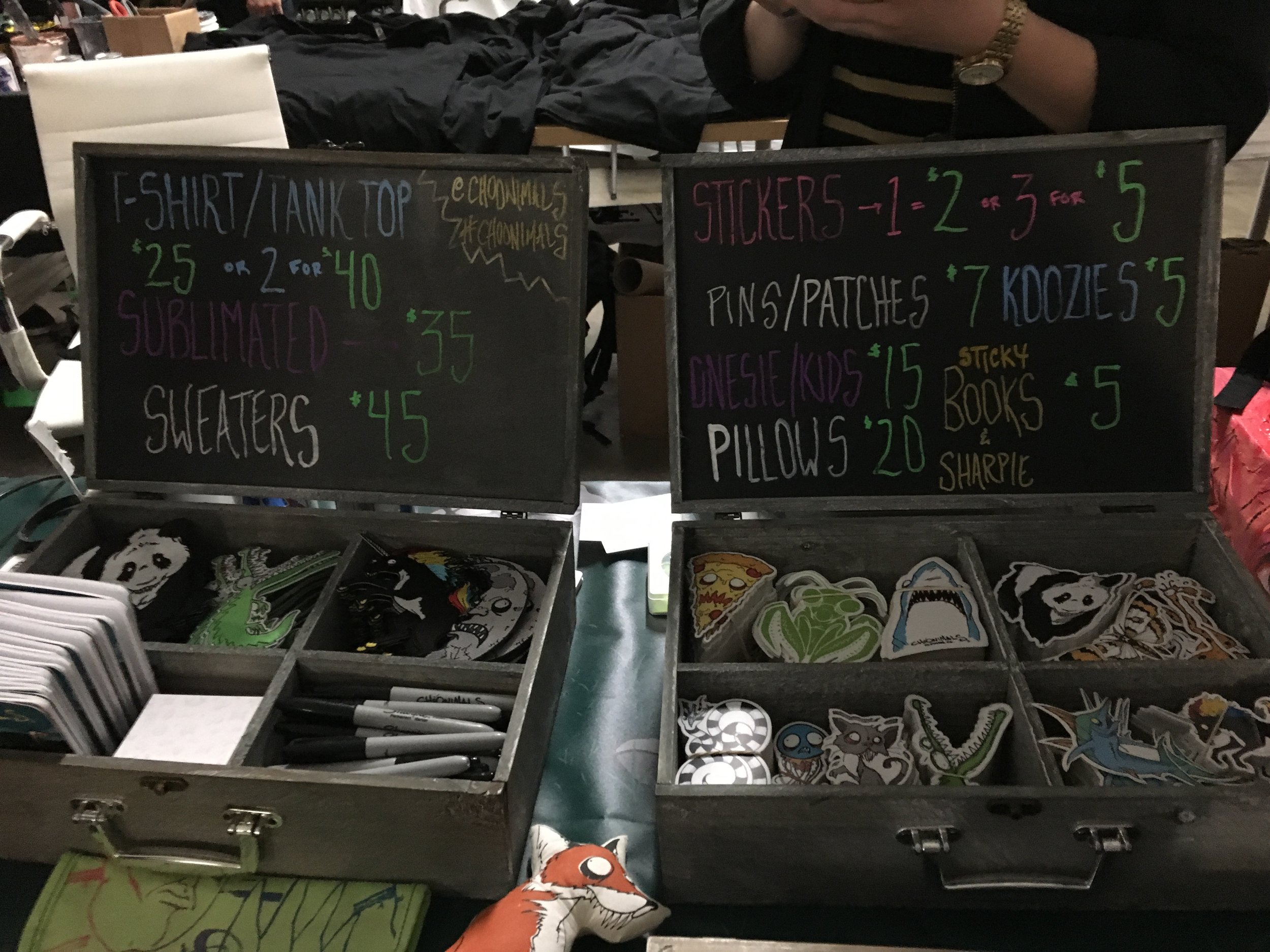

The final presentation was provided by Paul Watts of Graffiti Removal Services. Watts is also a board member of Friendly Streets. It is clear that one of the main functions of these summits is to provide a marketing venue for profit-seeking graffiti clean-up companies.

To clarify some of these misconceptions about PSAA…

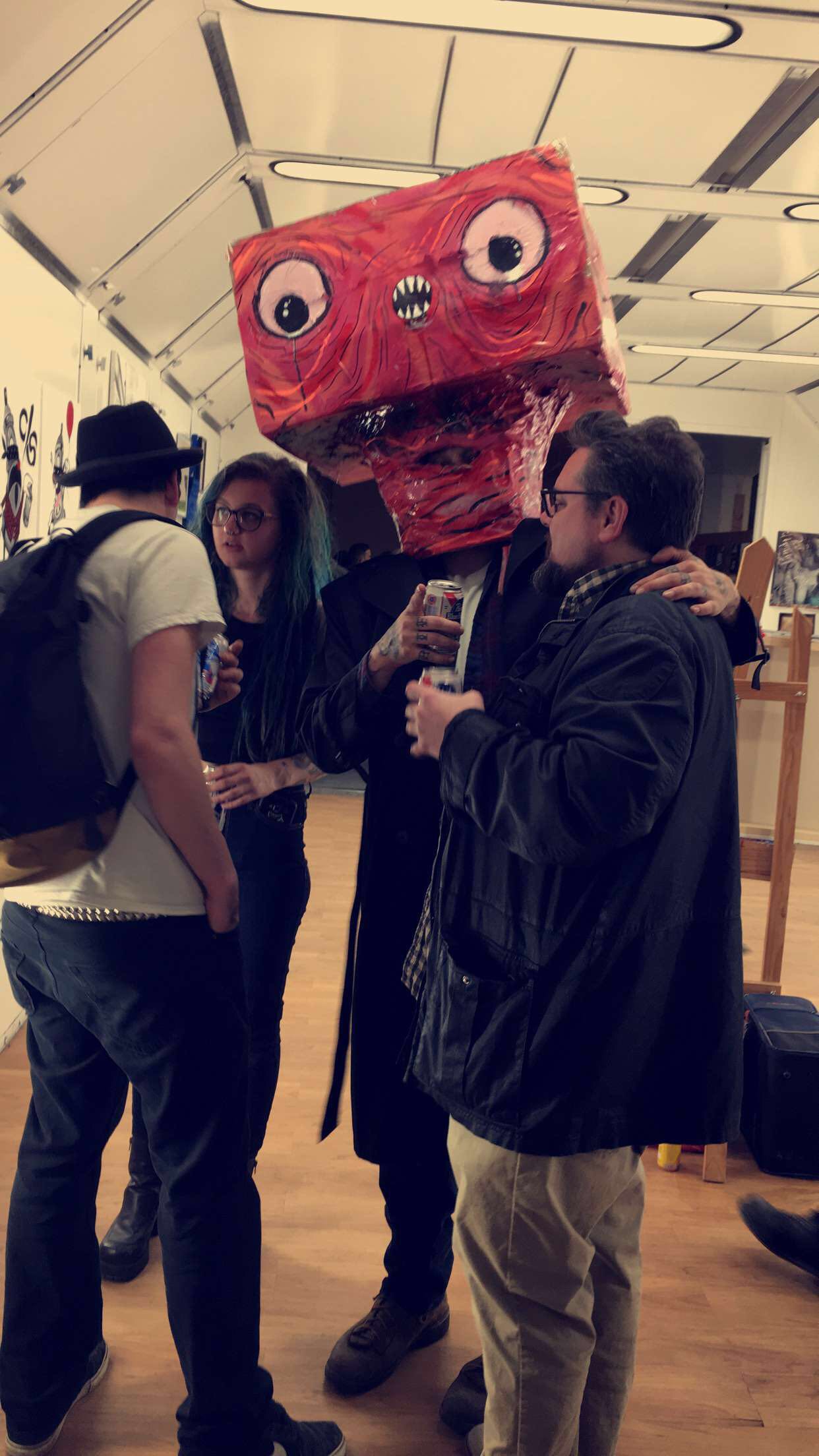

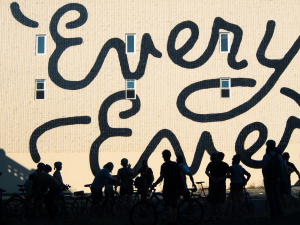

For two years, PSAA has worked to build bridges and relationships within the city. We want to help promote all forms of public art in Portland.

RACC has been willing to meet with PSAA and listen to our concerns, ideas, and suggestions. We are concerned that Toscan suggested, in a public setting hosted by the City’s Graffiti Program, that community groups like PSAA should not be associated with. Isn’t it the duty of all public entities to be willing to meet with and at least try to understand the communities they represent and serve?

PSAA is open to speak to anyone who wants to know more about our mission and purpose. We have requested meetings with various representatives from the City over the past two years. To date, our requests have been mostly ignored.

As of 2013, PSAA is a volunteer-run community group. We do not make any money advocating for public art. We are open to opportunities for receiving city and/or private funding for specific art projects (such as murals, curated walls, etc.).

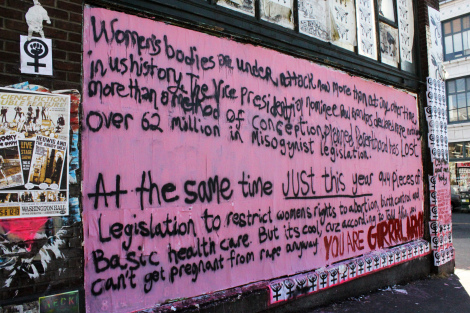

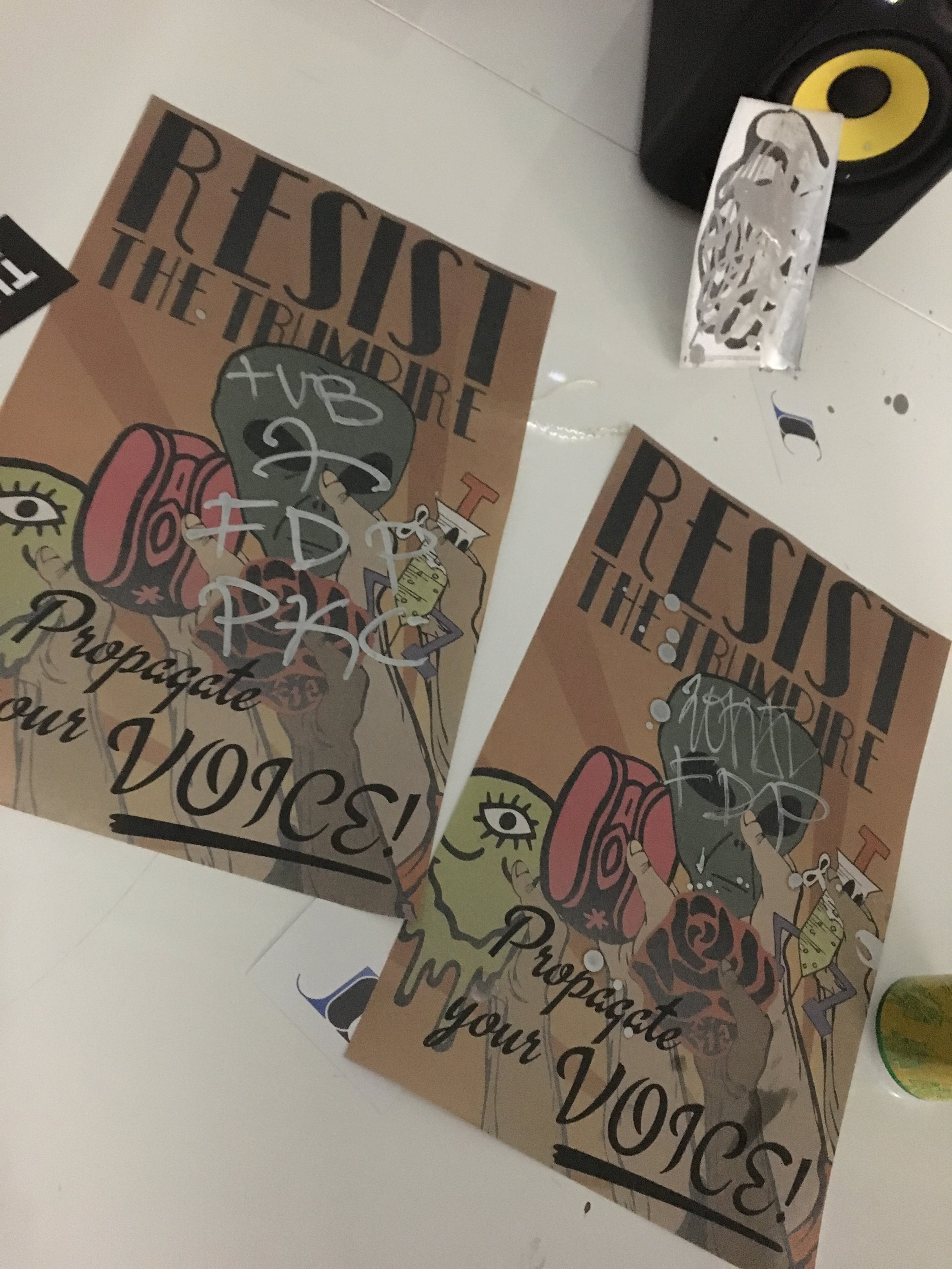

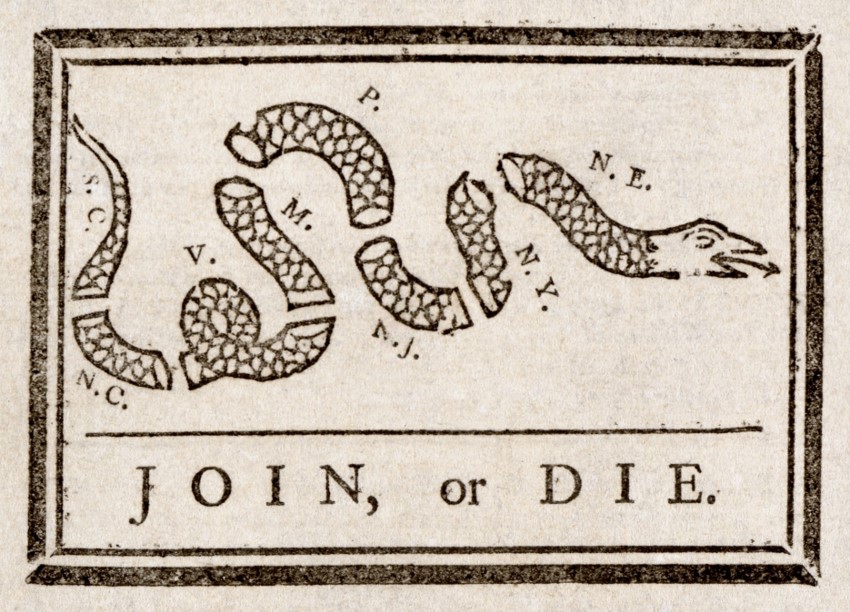

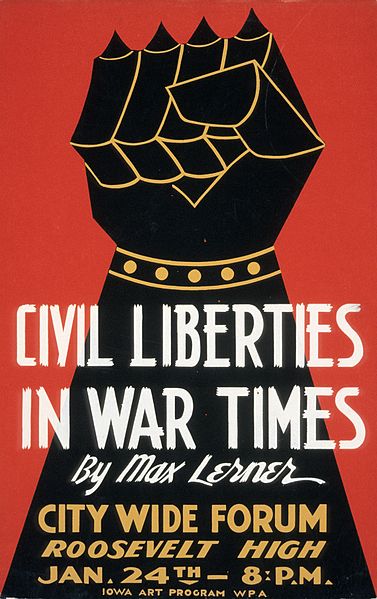

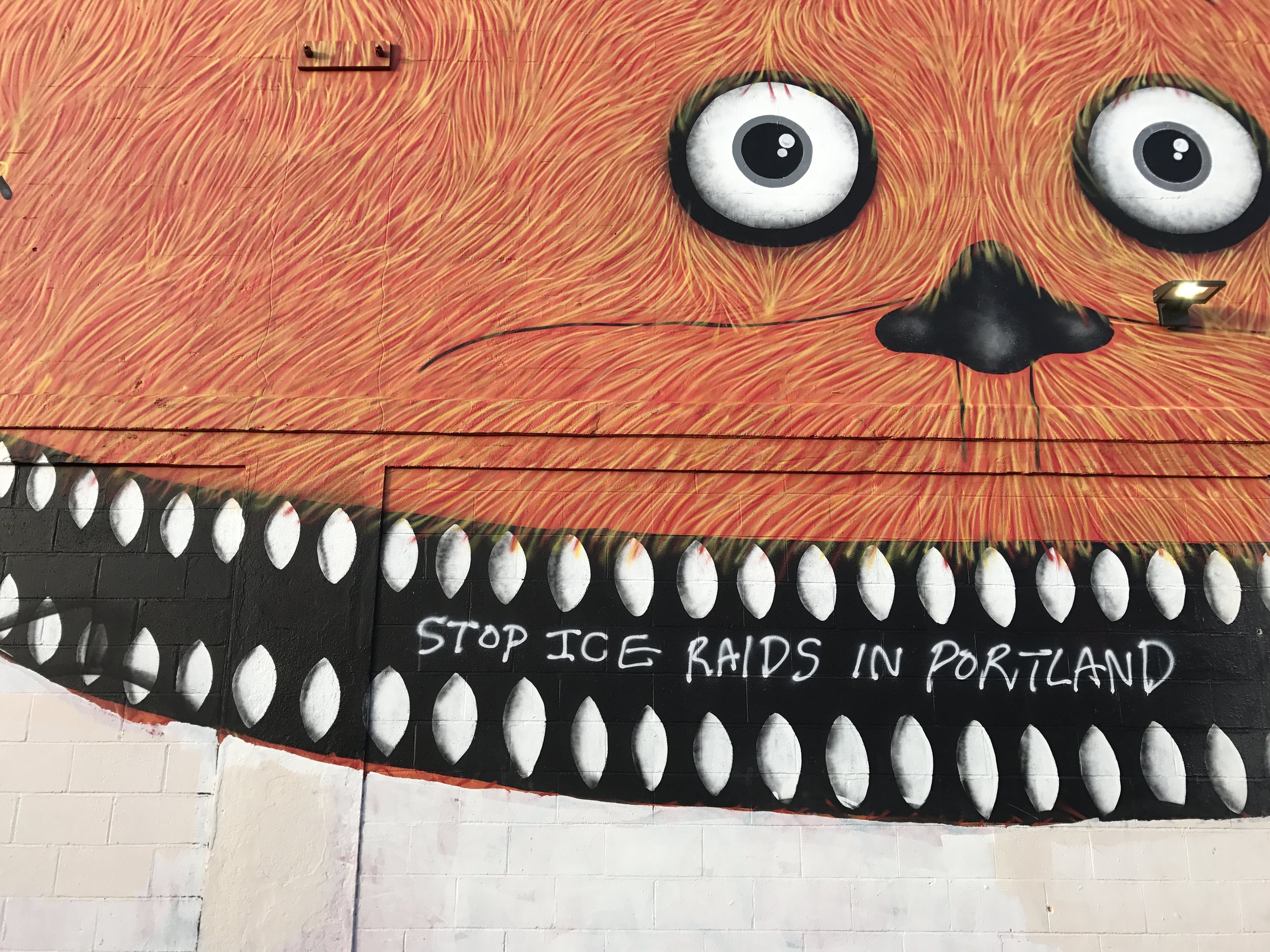

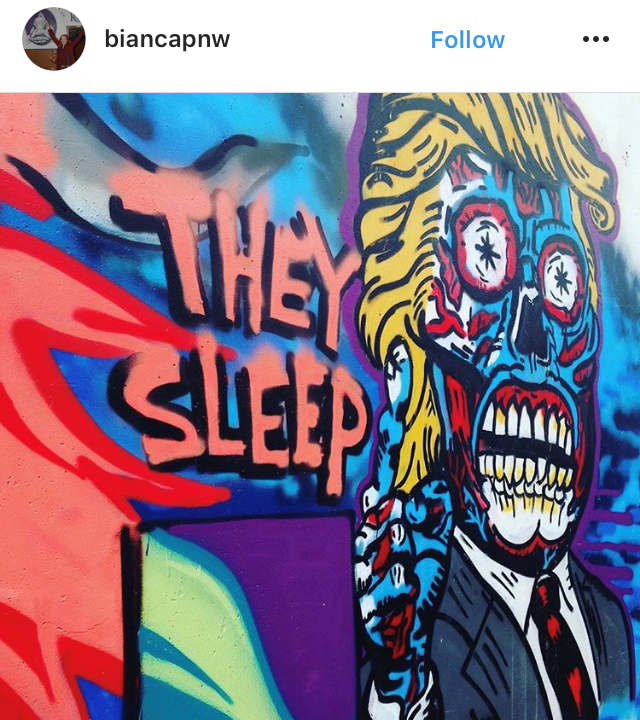

PSAA exists because we feel passionately about the public’s right to free speech, public space, and the city. We see these rights as essential ingredients for preserving a democratic society.

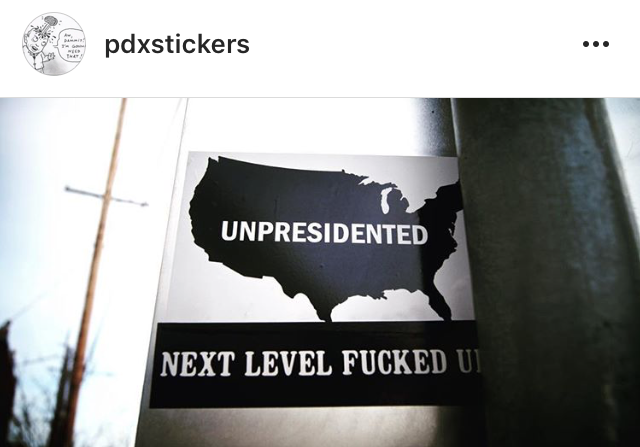

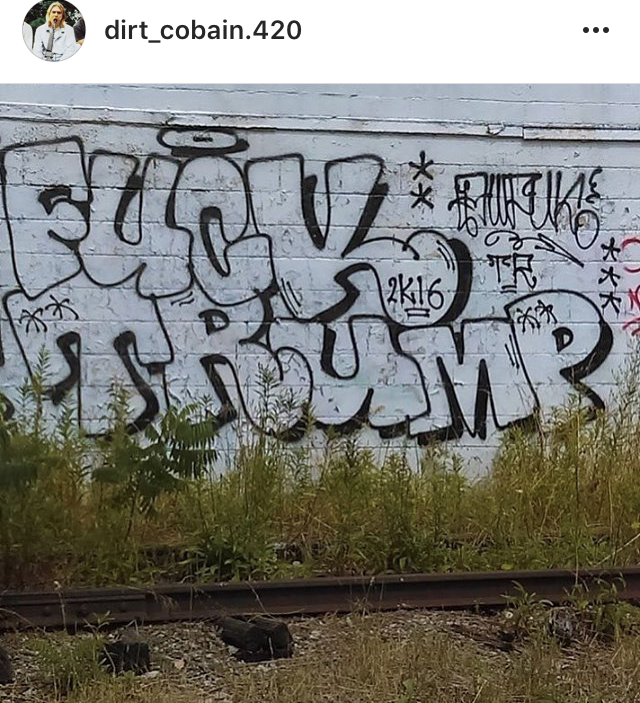

In general, PSAA does not believe that graffiti is an automatic sign of urban decay or distress. Like everything, it is place-specific and the larger context and intent should always be taken into account. We see the vast majority of graffiti in Portland as a sign of urban vitalization, vibrancy, energy, and urban culture-building. We also appreciate the history of graffiti and hip hop culture and recognize it as a valid form of self-expression.

It was unprofessional and irresponsible of the City of Portland to host this event without verifying whether or not its content was accurate. Toscan’s “wild guess” statistics are now being repeated in news articles, including one by Don MacGillivray recently published in the SE Examiner. If the Summit is going to host presentations by academics, they should at least be presenting legitimate statistics.

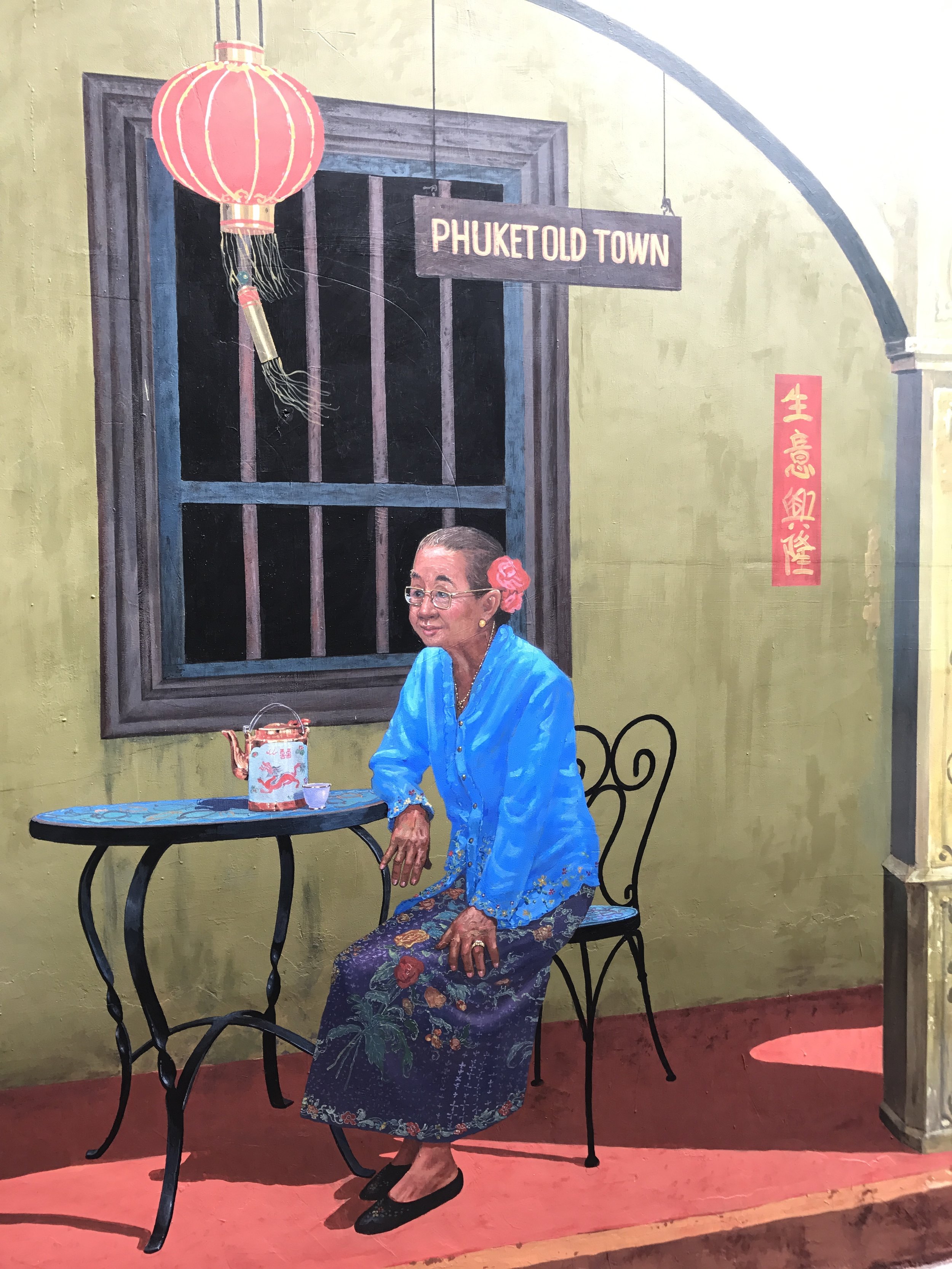

Commendably, this year’s Summit presented a few alternatives to simply criminalizing graffiti artists, such as the RestART program. However, we are disheartened to hear that Portland’s Graffiti Program is not using their funding to re-instate the mural-assistance program that was cut a few years ago.

We encourage everyone to contact their neighborhood and City representatives, and share your thoughts. We’ve been told the commissioners and neighborhood association presidents are good people to start with. Leaving your mark in public can have an effect, but speaking directly to those in power can have quite an impact too.

![Jessica and Jenny dress up downtown’s deer. [Photo by: Travel Portland]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1475722286013-CH04PFRIW9V7RKU22Z3P/Jessica+and+Jenny+dress+up+downtown%E2%80%99s+deer.+%5BPhoto+by%3A+Travel+Portland%5D)

![UglySweaterPDX 2014 [Photo by: Gina Murrell]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1475722319879-L46UH97OBUGHTGK6B6II/UglySweaterPDX+2014+%5BPhoto+by%3A+Gina+Murrell%5D)

![Claudia knits on some leg cozies [Photo by: Jaime Valdez]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54c5d2a7e4b0df35f166e6f8/1475722364327-ZFZ5AA2RI070N7BGIWJU/Claudia+knits+on+some+leg+cozies+%5BPhoto+by%3A+Jaime+Valdez%5D)