Portland is a city that by all appearances is constantly in flux. Nowhere is this more noticeable than in North Portland, where the Alberta Arts District draws thousands of people each month to its Last Thursday, where collectively-inspired permaculture gardens explode into vibrant natural canvases in lots that dandelion weeds and thistle once overwhelmed, where old bike parts and other rusty recycled metals decorate gates and archways, and where purposeful paint sprawls across intersections, bike lanes, and otherwise crushingly quotidian surfaces.

While Alberta Street has drawn ample attention as being a revitalized center for art, commerce, cuisine and cooperatives, commuters and bikers along N Williams Avenue have noticed a steady increase in the level of commitment from the neighborhood and local artists to create a more community-oriented and visually appealing thoroughfare.

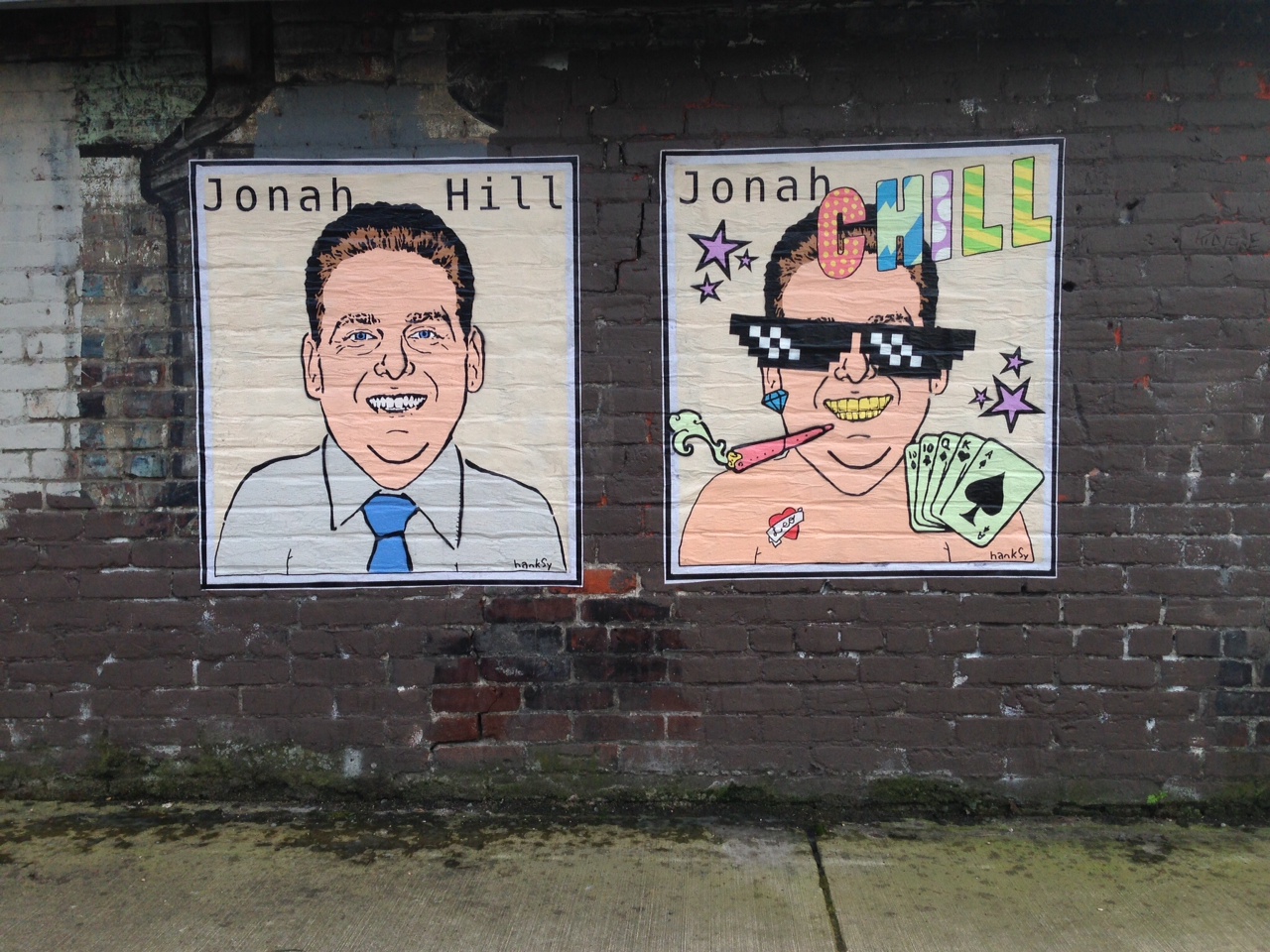

Formerly dotted with forbidding, unused lots, strewn with the obligatory broken glass, and tagged with a heavy saturation of graffiti, the stretch now boasts several community gardens, Village Building Convergence’s Boise Eliot public market, and several community mural projects that cover small plywood frames or entire two-story building facades.

One such mural lies at the intersection of Williams and NE Wygant. Formerly the site of an upholstery store, and attached to a residential unit, the building was frequently the target of graffiti artists and the city seemed to neither have the willpower or resources to address the situation. Now a colorful panoply of murals on three sides, the city has stepped in to serve a notice that the murals must be effaced.

Flash back to several months ago, when residents of the house began to dialogue with the graffiti artists by creating their own visual expressions on the building. A local painter/muralist noticed the building and approached the residents about opening up the space for a mural project.

The residents pooled their resources together to rent the empty space – which they likened to an “empty, cold, concrete cave” – and turn the exterior into a display of art, with an interior that would be a “warm, inspiring den of community-building and artistic creation.” A sign was raised on the roof that heralded Portland’s new “Arts Base.”

The property owners gave permission to paint over the drab and defaced walls, and the idea was generated that murals would be painted to feature a “rotating showcase of local talent,” according to outreach communications from the project organizers.

People in the surrounding Humboldt neighborhood were contacted and invited to give their feedback and express any concerns about the project. As the tagging began to subside, all that seemed missing was an interest from the City in funding this graffiti abatement project.

The project continued informally, and several months later, people began to take notice. One resident recalls people constantly coming by to photograph the murals and commenting on how beautiful they looked.

A nearby neighbor came to paint her own mural on the walls. A local group with the moniker “Bike Temple” approached the organizers to rent space in the building. Other individuals seeking studio space for larger projects started to take an interest in the space.

Organizers raised money as they could and supplemented the rest with meager teachers’ pay, with the intention that it could some day be a self-sustaining space. “We’re trying to do something that’s benefiting the community,” says one organizer.

Enter the Portland Police Department’s Graffiti Abatement Office. In a public communication prepared by Program Coordinator Marcia Dennis entitled “How to Read Graffiti and What to Do,” she writes, “Graffiti, by legal definition, is vandalism. (See ORS 164.383 or Portland City Code 14B.80) It is the unauthorized application of markings on someone else’s property, i.e.,WITHOUT PERMISSION.”

The same coordinator has determined that the murals at Williams and Wygant have indeed met the definition of vandalism. A notice was served to the landlords to paint over the murals within ten days.

Property owners who had unquestionably given permission for the murals filed an appeal with the city to delay the repainting, but ended up withdrawing their appeal after poring over restrictive city codes. Many neighbors were surprised, confused, or angry that the residents were now being required to paint over the murals.

An organizer of Arts Base expressed their frustration, “It’s too much for them, too colorful, too loud . . . as long as we can keep it inside it would be great, but it’s hard to do a community art space when you have to keep it inside, when you can’t be loud, can’t amplify music, can’t have murals, can’t have a sign.”

Residents now have two weeks to paint over the murals, and the Graffiti Abatement Office Coordinator is rejecting further appeals, claiming that it is no longer in her “jurisdiction.” Organizers hold out hope that a sympathetic coordinator or specialist in whatever other jurisdiction the case is now in will authorize the mural project, or calls to the City Commissioner from community members might stay the date of execution for the artwork.

UPDATE: (Aug 8th, 2011) The City of Portland has allowed the murals to stay, and plans for new murals are underway. However, the City has found Arts Base to be in violation of city zoning statutes, alleging that the residential space is being used for commercial activities. While the organizers of Arts Base have gone in the red on their venture, they plan on complying with their property managers’ demands that they cease community art activities in the space in order to pass the City’s upcoming inspection.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN WATCHDOG INTERNATIONAL POSTED ON JULY 18, 2011 AND ENTITLED: COMMUNITY MURAL PROJECT FACES EFFACEMENT